The app for independent voices

In 1886, Kadambini Ganguly became the first Indian woman to practice medicine as a doctor in India. She did so by overcoming multiple obstacles.

She fought against the norm that women should be at home, taking care of children. She battled for her right to study and take exams to practice medicine. She challenged prejudice and the status quo and pushed colleges to allow women to pursue medicine.

A pioneer, Kadambini showed women can do it all: by managing her medical practice while raising eight children. She is the ultimate working mom.

Born in 1861 in Bhagalpur, British India (now Bangladesh), she benefited from the Bengali Renaissance—a reformist movement led by the Brahmo Samaj that challenged conventions in marriage, education, dowry, and women's roles. Her father, a Brahmo movement stalwart, supported her education.

Studying at the Hindu Mahila Vidyalaya, she was educated in math, science, English, history, music, and needlework.

The Brahmo Samaj leaders were divided on women's education. Some believed Bengali women should be educated, but not so educated that they would forget their place. Women's education excluded science and mathematics, as the syllabus was tailored to male ideals of perfect Hindu wives.

It was the norm to marry off a girl child at the age of 9. After that, her husband and mother-in-law would decide if she could study further.

Kadambini's family supported her pursuit of higher education and had the courage to defy cultural norms by not wedding her off.

The Bethune School, founded in 1849, played a crucial role in Kadambini's education. Seeing her determination, the Bethune School decided to recruit new teachers to teach her college-level classes, thus becoming Bethune College.

In 1882, Kadambini received her BA degree from Bethune College, becoming one of Bengal's first female graduates. However, her degree wasn't enough to secure her admission to Calcutta Medical College (CMC).

CMC officials and the Indian Medical Council deemed Indian women unfit for medical studies and believed the community wouldn't accept female doctors.

Public pressure, including support from newspapers like Brahmo Public Opinion, led to Kadambini's admission to CMC in 1883.

In an unexpected twist, on 12 January 1883, Kadambini married her friend, teacher, and guide, Dwarkanath Ganguly. She was twenty-one, her groom a widower who was thirty-nine and with two children of his own. This shocked many in the Brahmo movement.

But, Dwarkanath shared her values. He fiercely believed in educating women and became a lifelong supporter of her pursuits. Also, he had previously taught her at Hindu Mahila Vidyalaya.

In 1886, she appeared in her final exams at CMC but failed to graduate by just one mark in the subjects of materia medica and anatomy. She was awarded a GBMC (Graduate of Bengal Medical College), a lesser qualification but it allowed her to practice.

In 1888, she started working at Lady Dufferin Women's Hospital in Calcutta, India, becoming the first Indian woman practising doctor.

She overcame deep prejudice from conservative Hindus. Being a mother, working at the hospital all day and taking care of her large family in the evening, was still a threat to conservative Brahmos in particular, and to conservative men everywhere. In 1891, the Bengali magazine Bangabasi called her a whore.

Her husband Dwarkanath Ganguly took the case to court and won, with a jail sentence of 6 months meted out to the editor of the magazine.

But working at the hospital, she was treated as inferior to the British-educated women doctors. Denied charge of a ward- the only way to acquire skills, she travelled to Edinburgh in 1893 to obtain additional qualifications from the Royal College of Surgeons.

Kadambini spent only a few months in Edinburgh. That was enough for her to accumulate several diplomas, which earned her the coveted superintendent position at Lady Dufferin Hospital.

Later, she opened her own practice. In her own discreet, hardworking way, she paved the way for other women to become doctors and changed the perception that women should be confined within their homes.

She was privileged to be supported in her endeavours by her family and husband, a rarity at the time.

Death came suddenly for Kadambini on 3rd October 1923. She died on the job.

If you enjoyed this story, please read Lady Doctors: The Untold Stories of India's First Women in Medicine by Kavitha Rao. This is where I learned about Kadambini's story.

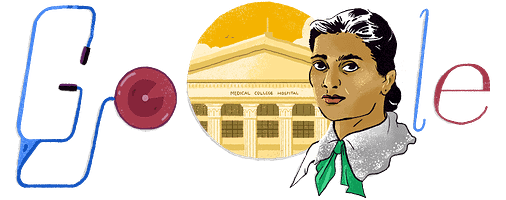

On 18 July 2021, Google celebrated Ganguly's 160th birth anniversary with a doodle on its homepage in India.