The app for independent voices

Haimabati Sen worked as a doctor, helping women have safe deliveries, for over forty years in rural Bengal, India.

Born in 1866, she became a widow at eleven. Braving all odds, she studied and worked while raising her five children. In her old age, she cared for 485 children, including day-old orphans, from her own funds.

Her father was a wealthy landowner. When the Bengal famine hit in 1872, six-year-old Haimabati would sneak into the storerooms, steal rice, and give it to the poor. Her father supported her actions, but her mother would beat her if she was caught.

The women in her family believed that if girls were educated, they would become widows. Marriage, having children, and managing household chores were considered a woman’s purpose. Thus, Haimabati was not formally educated but eavesdropped on the classes taught to the boys. Seeing her enthusiasm, her father helped her study in secret. One of the first books she learned to read was the Ramayana.

However, her father could not withstand the social pressure to get her married; an unmarried daughter in the house was considered deeply shameful. At nine and a half, Haimabati was married to a forty-five-year-old widower. In her caste, it was customary to marry their daughters to successful, wealthy men from a higher caste, hence the age difference.

Transplanted into her husband’s home, during the day, she and her husband’s two daughters played with dolls. At night, she would make excuses to avoid her husband’s advances. But her life took a drastic turn. Within two years of marriage, she was widowed when her husband succumbed to pneumonia.

Widows were shunned and forgotten by society. To make matters worse, Haimabati's beloved father died soon after. Her own family and that of her husband's cheated her out of her inheritance.

So common was the fate of widows that in Calcutta, many child widows turned to prostitution as a means of survival. At twelve years old, she knew the price of every handful of rice and every glass of milk.

Forced out, she went to Benares, hoping to live a dignified life. She survived by doing odd jobs but craved further education.

At twenty-three, lonely and seeking support—both financial and emotional—she married Kunja Behari Sen, a missionary of the same age. But she received no support from him.

Soon she was pregnant, but her baby was stillborn. Devastated, she developed a fever and was treated by Dr. Das and his wife Hemangini, whose care left a deep mark on her. She decided to go against the norm.

Money was hard to come by; Kunja, her husband, could not be relied upon. He would come and go as he pleased, preferring to spend his time at spiritual retreats in the Himalayas.

At the time, there was a need for women practitioners administering western medicine. To meet the demand, the Vernacular Licentiate in Medicine and Surgery (VLMS) was introduced, where less educated women were trained to work in hospitals, assisting doctors with deliveries and giving pain medication for childbirth.

Studying at Campbell Medical School on the outskirts of Calcutta, understanding the coursework taught by British doctors in English was a challenge. To overcome this, she paid a dispenser Rs.3 per month to learn dispensing.

Haimabati, now a mother, took her son to school and paid someone to watch him while she studied and worked. She stood first in her examinations, ahead of all the men, which irked them. They went on strike. For a week, the boys formed pickets, overturned benches, and threw bricks and stones at the women students. Under pressure, the administration awarded Haimabati the second prize and a scholarship of Rs.30 per month as a concession.

She made the money last as long as she could, but it was impossible to cover rent and food expenses. Often, she ate nothing, saving her money for her child. She had only one sari to wear and was forced to beg her neighbors for another.

With her degree in hand, she started working at the Hughli Lady Dufferin Hospital, also visiting clinics and homes. At the time, there was little emphasis on maintaining a clean environment for birth or understanding of women’s health. In such circumstances, she and her colleagues were responsible for bringing western medicine to remote rural areas, which had previously been the domain of quacks.

After thirteen years of marriage, her husband died, leaving Haimabati with five children—the oldest eight and the youngest only five months old. Alone once again, she gave in to her charitable instincts, taking in a number of orphaned children of every religion, most of whose mothers had died in her hospital. She also spent large sums of money arranging the weddings of girl orphans.

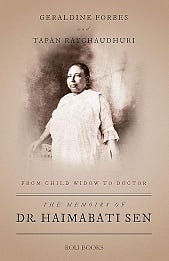

Her life paints a vivid picture of the tyranny forced upon child brides. Her memoir, published in 2000, was almost lost to time. It lay forgotten, stuffed in a trunk, and was printed 80 years after her death.

If you enjoyed this story, please read Lady Doctors: The Untold Stories of India's First Women in Medicine by Kavitha Rao. That is where I learned about Haimabati's story.