The app for independent voices

Many visitors to and researchers of ancient cultures of Ecuador will overlook the Yumbo in favor of the Inca as the country’s principal indigenous culture. But this is incorrect, as the Inca were invaders from the south who occupied a territory rich with its own overlapping cultures.

The Yumbo were an indigenous group that inhabited the cloud forests of western Ecuador, particularly in the Chocó-Andean region. Their territory stretched from what is now Carchi to the Esmeraldas province, where they lived in harmony with (and actually enhanced the biodiversity of) the dense forests and the surrounding mountains.

Their food forest design system was known as the chakra integral, (an indigenous agroforestry practiced in the forests of Ecuador for millennia before the arrival of Christopher Columbus) Meaning "big round garden" in the pre-colonial Yumbo language, the chakra integral forms a landscape that resembles a mosaic, which is economically productive and ecologically friendly to the area’s biodiversity.

The Yumbo, were less militant and than the Inca (that were politically imperialistic and hierarchical) and while the Yumbo may not have created large imposing stone structures nor deadly machinations of military might, one might argue that their ecosystem “engineering” (advanced regenerative agroforestry systems) were lightyears ahead of imperialistic cultures as an expression of human ingenuity and sustainability (the real kind, not the fake U.N. greenwashing type).

These pre-Inca tribes had a massive role to play in building the history of Ecuador and altering forest ecology, species distribution and increasing biodiversity so that the landscape could support more humans.

The Tulipe valley, where the Yumbo lived for more than 2,000 years from 800 BC, is rich in archaeology today. Much of what survives allows researchers to build a picture of these peaceful food forest farmers and traders.

The Yumbo did not swear fealty or subservience to any single political leader but they shared a vision of forest tending and had traditions of reciprocity with the spirits of the land. They were strongly aware of the existence of other tribes or groups, and the benefits of trading with these peoples. Their recognition of mutual advancement through beneficial trade rather than conquest shows a remarkable level of sophistication in their thinking.

The Yumbo had developed an advanced understanding of the natural medicine from the plants around them, and they took this knowledge to the surrounding tribes. Due to this, and the rugged and inaccessible lands the Yumbo lived in, (in a similar way to how some of my Gaelic ancestors were viewed by “civilized”, city dwelling outside cultures) they also gained a reputation as witches or sorcerers.

The Yumbo were considered to be protectors of the forest and its resources. According to legend, they were blessed by the spirits of the trees, which granted them the ability to communicate with nature. This deep connection allowed them to protect the forests from external threats. The Yumbo were believed to have mystical powers. One of the most famous legends tells the story of the Tree Spirits, which were said to protect sacred groves in the Yumbo territories. When these sacred places were disturbed, the spirits would rise from the trees and punish those who dared to harm the forests.

Another essential aspect of Yumbo mythology is their deep knowledge of medicinal plants. The Yumbo were experts in the use of plants for healing, and it is said that they possessed knowledge passed down by the forest spirits. These plants not only had healing properties but were also believed to hold spiritual significance. Certain plants were used in ceremonies to invoke the help of the spirits, asking for guidance or protection.

Over time, they managed to expand from northwestern rain forests and the clouds of Quito to the coastline. As their culture expanded they expanded their food forests along with them. And this expansion was only possible because the Yumbo tribe made complex roads connecting their system of truncated pyramids, named Tolas. These pyramids were primarily residences of the forest architects of Yumbo society. Most of these artificial pyramids had many secondary purposes as well, acting as a shelter from flood in the rainy season or serving as lookout points for observing the surrounding land, planning for using fire to enrich soil, introduce key tree species for multi-generational food wealth to take root and ceremonies to honor the forest spirits.

As a result of this (regenerative biodiversity enriching) expansionist trade, agroforestry and ecology compatible roadbuilding, the Yumbo managed to unite the highland, Amazon, and northern coast regions of Ecuador. With the help of their road networks, designed via careful species distribution into the floor of the jungle and kept hidden amidst the dense vegetation they had built a trade confederation from the Andes to the Pacific.

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, the Yumbo population consisted of approximately 12,000 people – a high number for those times. However, it wouldn’t be long before the arrival of the Spanish that their population would decrease exponentially. Exposed to European diseases (against which they had no defense) and after a series of eruptions from the neighbouring Pululahua and Guagua Pichincha volcanoes (which managed to cover the region in ash), the Yumbos were decimated by the hundreds and thousands.

“You could go [along the river] where you wanted and homestead. the forest gives you all kinds of fruit and animals, the river gives you fish and plants. They had to be much more fluid, more hang loose, less coercive or people wouldn’t stay…[The people] were freer, they were healthier, they were living in a really wonderful civilization…orderly and beautiful and complex. The eye-opener was that you didn’t need a huge apparatus of state control to have all that.”

– Anna Roosevelt, archaeologist, author of Mound Builders of the Amazon

—————————

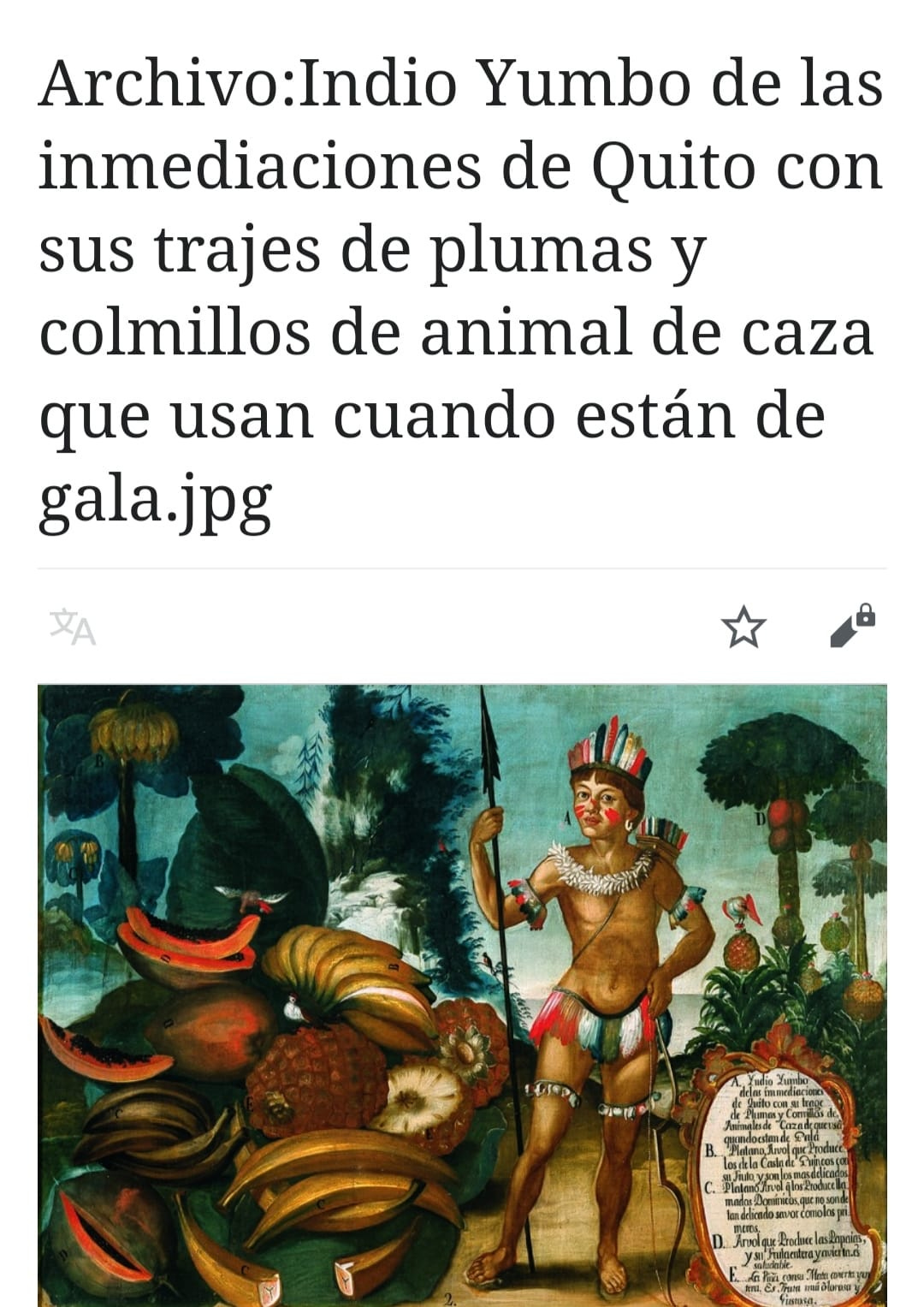

First Picture below shows a Spanish artist’s depiction of a Yumbo person (the dominant tribe of NW Ecuador up until 1650.) You can see how the artist emphasized the abundant diversity of tree crops in the mound of fruit in the foreground. The plaque on the left describes each fruit, and in the background are the mounded earthworks planted with forest gardens.

The other pictures show the sacred stone artwork of the Yumbo people. Notice the similarities to the works of my Pictish and Gaelic ancestors and their Ogham stones?

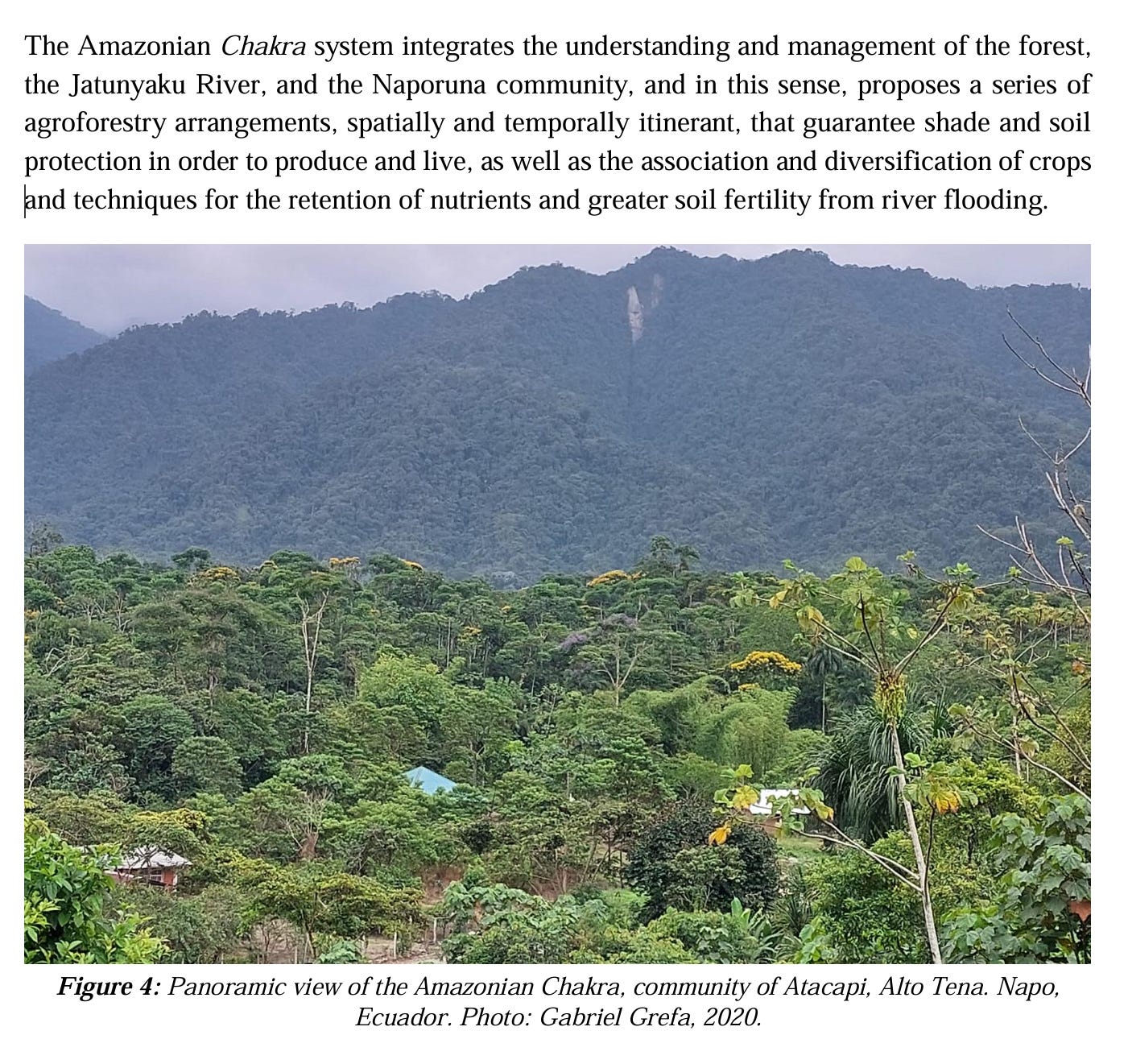

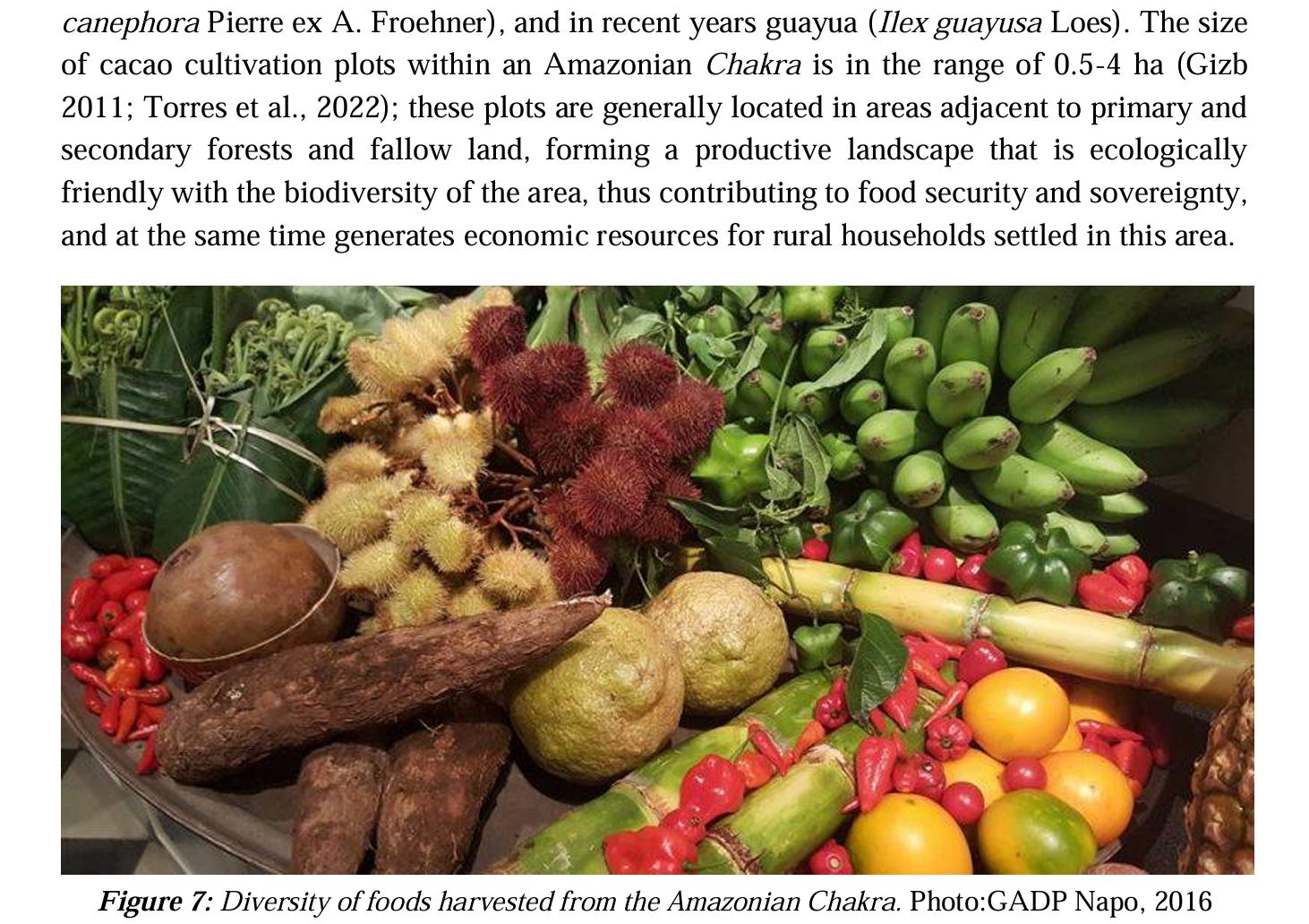

Last two pictures shows a modern day Yumbo style Chakra food forest and a harvest from a modern day Chakra Food Forest in Equador.

It would seem these cultures not only shared a reverence for forest tending, decentralized societal structure, ecological literacy and animist worldviews, they also apparently drew from the same well of spiritual knowing, perceived the will of Creator and expressed that truth in similar sacred geometry inscribed monuments (despite being separated by an ocean).

We here in modern western civilization have a long way to go before we can get back to that level of land stewardship on the scale of communities and entire regions filled with autonomous communities collaborating of their own free will and from the same ethos of animism and reciprocity. That said, the 7th generation that comes after us is whispering and calling out for us to plant the seeds so that those kinds of cultural expressions can once again be part of the lived human story on Earth. It starts with each of us holding a handful of seeds and a heart full of faith.