The app for independent voices

If you don’t know much about the Doctrine of Discovery and want to learn one thing about history (with profound implications in our modern lives) of true importance this year, I’d make it that.

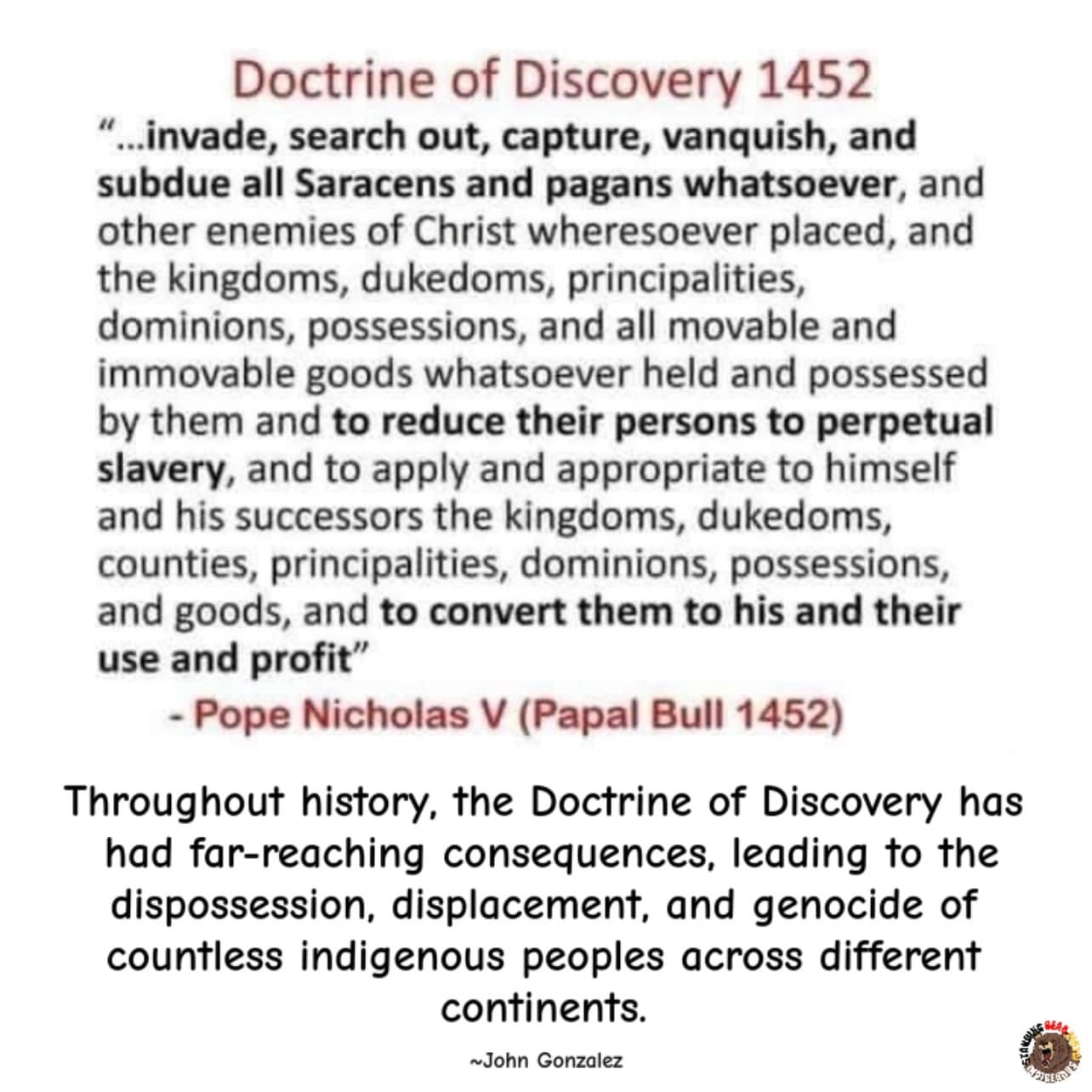

The doctrine is not ancient history. It’s a subtly hidden 500-year-old idea with tremendous and lasting global power. It takes the “I took it; now it’s mine” underpinnings of ownership further to “I saw it; now it’s mine.”

The Doctrine of Discovery, was articulated and hardened into U.S. law through the 1823 Supreme Court case Johnson v. McIntosh.

In that supreme court case, Chief Justice John Marshall slipped in “civilized” to equate with “Christian” and wrote that "discovery" of land was equivalent to ownership of it.

Johnson v. McIntosh stated outright that Native Nations could not own land; only European nations—and after them the United States—could. Part of that 1823 opinion contains the following baffling language:

“It has never been contended that the Indian title amounted to nothing. Their right of possession has never been questioned. The claim of government extends to the complete ultimate title, charged with this right of possession and to the exclusive power of acquiring that right.”

That language is all the more baffling because there is a long history of treaties defining coexistence, and even of land purchase transactions of a kind in some places, during the centuries of European presence in North America before the United States existed. Though it’s not so baffling when you consider that John Marshall, who judged and authored the opinion in the case, was himself a well-known land speculator. He and his father owned vast tracts of land, and anything the Supreme Court decided about land ownership rights would directly affect Marshall’s own fortunes.

Legal cases like this one are a reminder that, just because a law exists and can be enforced, doesn’t mean it’s just.

Steve Newcomb, author of Pagans in the Promised Land, showed how almost every recent and current battle in the U.S. and Canada between resource extraction and rights of land and ecosystems, such as Standing Rock or the Thacker pass lithium mine, or Fairy Creek, Coastal GasLink pipeline, the Mi'kmaq protecting the land against fracking in Elsipogtog and the current battles going on with those indigenous peoples that oppose the lithium mining in the Boreal Forest can be threaded through legal precedent to end up back at Johnson v. McIntosh.

The doctrine’s effects are vast. Johnson v. McIntosh gave justifying language to anyone in the world who wished to perpetuate the project of colonialism: take the land, claim ownership over it, and profit from the gifts it holds, no matter what the consequences to anyone else.

These documents are important. They’re important historically because of what they set in motion as European empires spread out across the planet. They’re important because, through the U.S. Supreme Court, they gave license to ever more ravenous land theft in 19th- and 20th-century North America, and were then referenced for similar ambitions throughout the world.

And they’re important because their influence still defines relationships of colonialism today. They’re one of the bases for nearly every claim of absolute land ownership or property right—gold or lithium mining in a place where people have relied on a healthy ecosystem for millennia, for example—and are much of the reason that it’s so difficult to defend the rights of life and well-being over the right to extract and profit.

In an interview with physician and activist Gabor Maté, in which he said to his interviewer:

“You know what the Canadian government hasn’t apologized for yet? We have not apologized to Indigenous people for taking their lands and their resources and their forests and their rivers and their oceans. Why haven’t they apologized? Because they’re still taking it.”

If you got on a boat tomorrow and sailed around on whatever ocean is closest to you, and came across an inhabited island you’d personally never heard of, you might be able to tell yourself you’d discovered it. If by “discover” you simply mean you saw or observed or found something new to you, by all means, go ahead and say you discovered something.

Does your sight of that land, your “discovery,” go further? Does it give you rights of ownership over the island and its people? Why wouldn’t you say they discovered it first, since they’re living there?

But maybe there’s gold, or timber, or cinnamon trees—something you want to make money off of, which you can only do if you claim the island and everything and everyone on it as yours to control. You have to come up with some reason why you, and not the people already living on the island, have the right to benefit from what it offers. “Discovery” must be mangled to mean something more than it does. It must equate to possession.

So you make a ruling that you’re more “civilized” than the people of the island and therefore your discovery has weight while their being there, their existence on the island, doesn’t. You come up with a doctrine that gives rights of ownership not to the people inhabiting a place but to the most recent person to come across it: you. And you back that ruling with military force.

That is what "the Doctrine of Discovery" was used to do.

Sarah Augustine, author of "The Land Is Not Empty" and co-founder of the Coalition to Dismantle the Doctrine of Discovery, summed up the doctrine as having “legalized the theft of land, labor and resources from Indigenous peoples across the world and systematically denied their human rights” for over five centuries.

I feel like we cannot truly heal and move towards a more regenerative, equitable, honest and hopeful future for our human family without honestly looking at what brought as to where we are today.

What I share below is the basis for the legal framework that allowed for the formation of Canada, The United States, Mexico (and all the nations south), Africa, Australia (and many other nationstates). This is a lesser known facet of colonial history and the foundation for all modern legal claims to land ownership and I feel we need to bring this wound that was inflicted onto our human family by hegemonic entities to light (so that it can be healed).

I know quite a few people that talk about how glorious, civilized, advanced and just "The Canadian Constitution" (aka Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms) or The United States Constitution is for protecting "freedoms such as the freedom of speech and religion" and protecting "personal wealth and property".

My question to these people that put the edicts (and "constitutions" etc) of involuntary statist government regimes such as Canada and the US) on a pedestal is as follows:

Were these wonderful distillations of civility called "constitutions" not in place when the Doctrine Of Discovery and Manifest Destiny was being used (in the supreme court) to "legally" dispossess and forcibly relocate indigenous people from their land in the 1800s?

and, Why were those humans not included in these "protections" and "freedom from tyranny"?

Here in Canada we have a "bill of rights" and "human rights" etc , but if some indigenous people got in the way of industrial development those supposed rights got thrown right out the window.

It seems to me that many of these statist laws and "constitutions" have lofty aspirations, but where the rubber meets the road, the oligarchy, corporations and established hegemonic family lines get traction, throwing many others under the bus.

I think our human family can do better than these flimsy preferential "constitutions" proffered by involuntary governance structures.

Therefore, I do not recognize the legitimacy nor authority of the Canadian Government, United States government, British government (nor any other statist regime which based the formation of its nationstate on nefarious and fallacious edicts such as The Doctrine Of Discovery). I reject the edicts of these organized criminal syndicates (exploitative nationstates) as holding any legitimate authority whatsoever.

I stand in solidarity with all of my indigenous brothers and sisters globally in advocating for the stewardship of land by the people that reverently tended and protected the forests, lakes, rivers, plains and coastlines in such a way (and for the duration of time required before colonization occurred) where climax ecosystem expressions and increased biodiversity was present when the land was under their care. I stand in solidarity with all of my indigenous brothers and sisters globally that can demonstrate (through action) whenever possible, their continued ability and willingness to carry on those regenerative traditions to act as keystone species in their respective bioregions.

——————————————

Max Wilbert Derrick Broze derrick Paul Grinnell Jason Earth Heart Susan Hyatt Rob Lewis Joy of Resilience Diana van Eyk Michael Campi Kristen Morrissey Anne Settanni Zane Treks John Scarlett David B Lauterwasser The Honest Sorcerer Kollibri terre Sonnenblume Christine Schoenberger George Price Elizabeth Luke Dodson Cheerio Alison Moss