Discover more from God of the Desert Books

Theodore Roosevelt, Explorer of the Amazon

The book details a post-presidential journey into the unknown.

After losing the 1912 election, Theodore Roosevelt decided to go where no ex-president had gone before. He, his son Kermit, and a team of men set out to explore an uncharted section of the Amazon. Not everyone returned, and it’s astonishing that any of them survived.

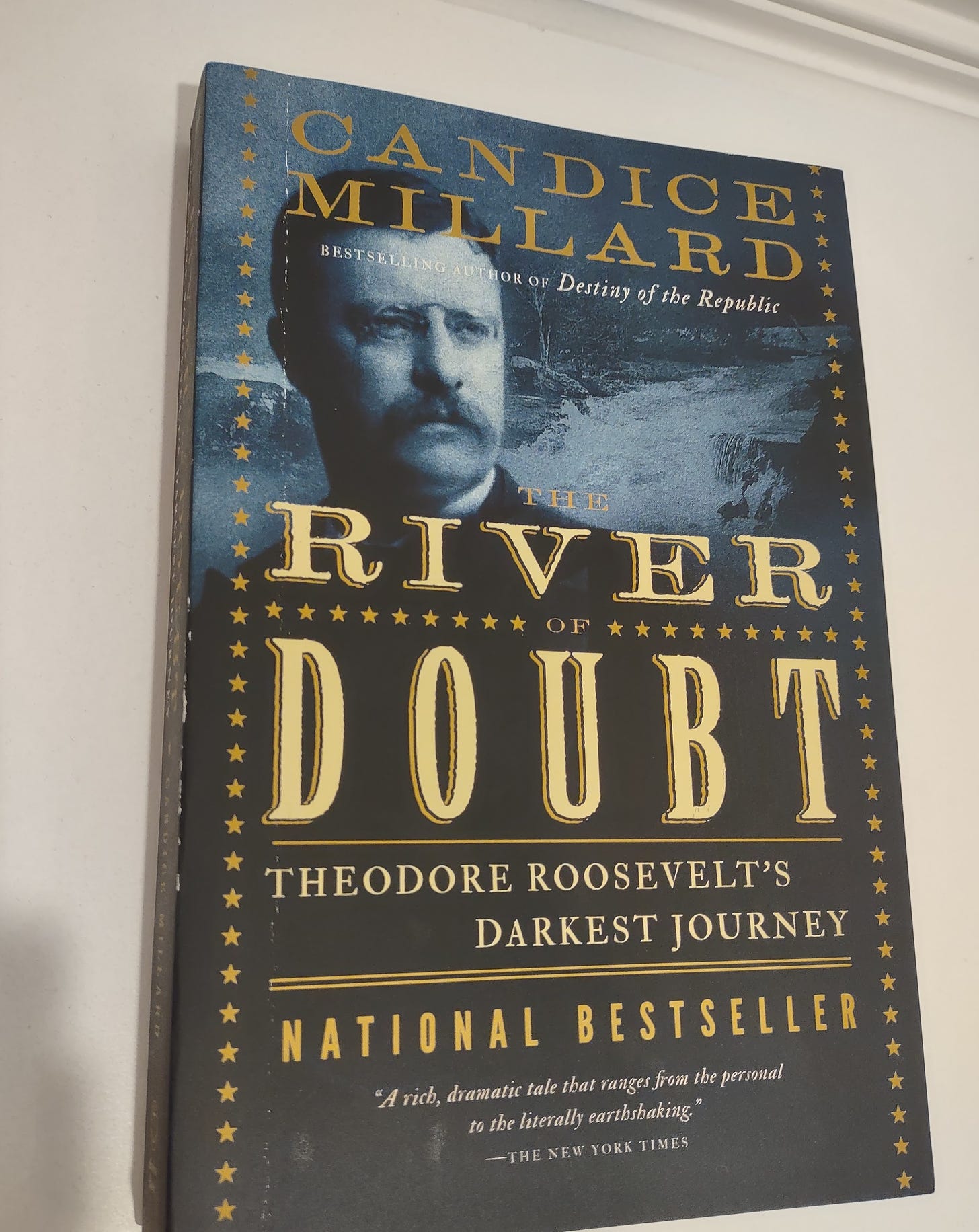

Candice Millard details the harrowing ordeal in The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt’s Darkest Journey.

When it comes to nonfiction, I tend to gravitate toward topics rather than specific writers, but there are a few nonfiction authors who always get my attention. The short list includes Ron Chernow and Walter Isaacson, as well as Millard.

I’ve already covered Destiny of the Republic and Hero of the Empire, and as with those excellent books, Millard writes River of Doubt in such a way that I could easily see this becoming a TV or streaming miniseries eventually. She gets inside the heads of these historical figures as much as possible without straying from the factual path, and she achieves thoroughness without sacrificing narrative momentum.

Here, Millard details the expedition and all the major players. If you know Roosevelt’s basic biography, you know he died in 1919, not in 1914 when the bulk of the expedition occurred. But it’s easy to forget that as we’re wondering how on earth he’s going to get out of this.

At one point, Roosevelt was fully prepared to die in the Amazon.

While trying to free a trapped canoe, he waded into the water and slipped up. His shin struck sharp rock, which drew blood. In normal circumstances, it would have been a fairly minor injury. But this was a jungle that remained untouched by civilization until Roosevelt and his team ventured through it.

“For Roosevelt, in a dripping rain forest where every muddy step throbbed with bacteria, parasites, and other disease-carrying insects, this injury was potentially fatal,” Millard writes.

Among Roosevelt’s deepest beliefs, according to Millard, “was that the health of one man should never endanger the lives of the rest of the men in his expedition.”

In Roosevelt’s own words:

“No man has any business to go on such a trip as ours unless he will refuse to jeopardize the welfare of his associates by any delay caused by a weakness or ailment of his. It is his duty to go forward, if necessary on all fours, until he drops.”

He held himself to even stricter standards. While campaigning in 1912, a man shot him, but since the wound didn’t appear to be fatal, Roosevelt insisted on delivering his speech—the bullet in his chest be damned.

Millard observes:

“From a very young age, he had been prepared to die in order to live the life he wanted. When a doctor at Harvard told him that his heart was weak and would not hold out for more than a few years unless he lived quietly, he had replied that he preferred death to a sedentary life.”

His successor, William Howard Taft, believed Roosevelt had something of a death wish.

“The truth is, he believes in war and wishes to be a Napoleon and to die on the battle field,” Taft said. “He has the spirit of the old berserkers.”

Exploring the Amazon fit Roosevelt’s criteria of a meaningful death. Millard quotes him as saying:

“If I had to die anywhere, why not die in helping to open up to the knowledge of the world a great unknown land and so aid humanity in general and the people of Brazil in particular?”

Even if he was hoping for a glorious conclusion to a remarkable life, Roosevelt seemed even more concerned with ensuring that he didn’t cause anyone else’s death. He brought along a lethal dose of morphine in the event that he became a hindrance. As his infection worsened and he grew sicker, Roosevelt decided that the time had come to take the drug.

“Roosevelt refused to slow down the expedition when each man was fighting for his own life. For him, this was not about suicide, it was about doing the right thing,” Millard writes.

Speaking “without a trace of self-pity or fear,” Roosevelt informed Kermit and friend George Cherrie that he would be going no farther. They were to save themselves and find a way back to civilization.

Kermit disagreed.

Millard describes the relationship between father and son and how their roles now switched for the first time:

“In the fraction of a second that passed between Roosevelt’s grim declaration and Kermit’s reaction, father and son reversed the roles that had defined their relationship, and which neither of them had ever questioned… Roosevelt had molded Kermit in his own image, creating a young man who, given a goal, would fight with everything he had to achieve it.”

Millard adds, “Recognizing the resolve on his son’s face, Roosevelt realized that if he wanted to save Kermit’s life he would have to allow his son to save him.”

Read the whole remarkable book. And really, read anything by Millard.

I loved this book!