Discover more from David Friedman’s Substack

James Scott

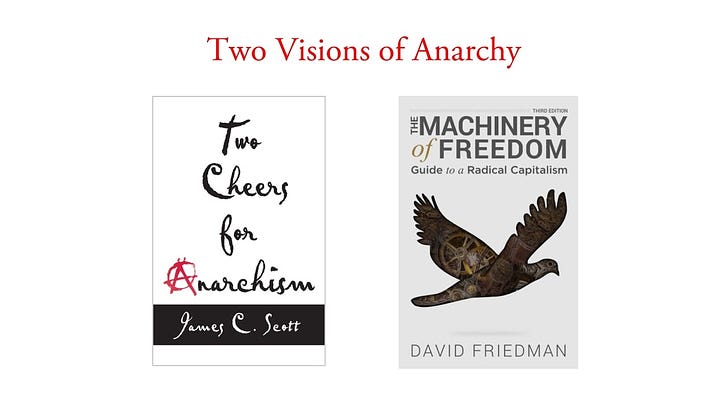

Some years ago I had a debate on anarchy with James Scott; Robert Ellickson was moderator cum participant. A recording is available online.

I had read two of Scott's books. One, The Art of Not Being Governed, is about the existence of extensive stateless areas in South-east Asia over a very long period of time. From the standpoint of the adjacent states the stateless areas, typically hills, mountains, and swamps, are populated by "our ancestors," people who have not yet developed far enough to create or join states. By Scott's account, on the other hand, much of the population of the stateless areas is descended from people who were once in states, much of the population of the states from people who were once stateless. The pattern as he sees it was a long term equilibrium based on the difficulty of maintaining a state when population densities are low and transport and communication slow. When a state is doing well it pulls in people, whether voluntary immigrants or the captives of slave raids, from the adjacent stateless areas. When the state is doing badly, the flow of people goes in the other direction, fleeing taxes, conscription, and other benefits of being ruled.

Part of what I found interesting was Scott's discussion of features of stateless areas that make it unprofitable for adjacent states to annex them. To take one small example, once wheat or rice is harvested and stored an invading army can seize it. Root vegetables remain in the ground until they are eaten, so in order for an invader to seize them it has to first find them and dig them up. It was very much an economist's point of view, one that suggested an approach to the question of how a modern anarchist society could avoid annexation by adjacent states that I had not considered, that military defense is only one part of a broader set of solutions.

The other book by Scott that I read was Seeing Like a State. Its central theme is the ways in which states have attempted to reorganize societies in order to make them easier to rule, to make the territory look more like the rulers' necessarily simplified map. It is harder to rule a country if the people do not all speak the same language. It is harder to tax land if the country contains a wide variety of systems of land tenure and units of measurement. It is harder to keep track of who has or has not been conscripted if there is no uniform and consistent system of names. It may be possible, sometimes has been possible, for a state to change those features of a country in order to make it easier to rule and tax.

A secondary theme is the amount of damage that states have done in the process of revising societies to be easier to rule and then ruling them.

While it was obvious to the author that his account would be attractive to market libertarians such as myself he went to some trouble to make it clear in the book that he was not himself one of those icky market libertarians. His part of our recorded exchange may help suggest why.

Another theme that he devotes considerable attention to is "high modernism," the belief that modern science lets us figure out how everyone should do things and, once we have figured it out, make them do it that way. Examples include planned cities, Soviet collective farms and attempts by first world agronomists to tell third world peasants what to plant.

Adam Smith, another icky market libertarian, had something to say on the subject:

The man of system, on the contrary, is apt to be very wise in his own conceit; and is often so enamoured with the supposed beauty of his own ideal plan of government, that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it. He goes on to establish it completely and in all its parts, without any regard either to the great interests, or to the strong prejudices which may oppose it. He seems to imagine that he can arrange the different members of a great society with as much ease as the hand arranges the different pieces upon a chess-board. He does not consider that the pieces upon the chess-board have no other principle of motion besides that which the hand impresses upon them; but that, in the great chess-board of human society, every single piece has a principle of motion of its own, altogether different from that which the legislature might choose to impress upon it.

Scott Alexander

A long time ago Scott Alexander, a blogger I think highly of, wrote a non-libertarian faq. Some years after it was written I came across it and responded by email. He replied, I replied, and I eventually got around to converting the exchange to a web page.1 These are a few of what I think are the more interesting points.

Scott correctly explains declining marginal utility of income then incorrectly writes:

50% of what a person with $10,000 makes is more valuable to her than 50% of what a billionaire makes is to the billionaire.

Progressive taxation is an attempt to tax everyone equally, not by lump sum or by percentage, but by burden. Just as taking extra movie tickets away from the person with a thousand is more fair than taking some away from the person with only two, so we tax the rich at a higher rate because a proportionate amount of money has less marginal value to them.

If you work through the mathematics of the declining marginal utility argument for progressive taxation you will discover that it is only an argument against lump sum taxation. It is easy enough to write a utility function with declining marginal utility for which the utility of the second half of an income of $100,000 is greater than the utility of the second half of an income of $50,000; utility per dollar is lower but the second half contains twice as many dollars. For any structure of taxes more progressive than a lump sum tax, including a flat tax, there is some utility function consistent with declining marginal utility for which that structure imposes a larger utility cost on higher income taxpayers.

Declining marginal utility can support a utilitarian argument for progressive taxation but an equal burden argument requires a stronger assumption, how strong depending on how steeply graduated the taxation is. You get equal burden from a flat tax, each taxpayer paying the same fraction of his income, if utility equals the logarithm of income, making marginal utility inverse to income.2 The proof, as the books say, is left as an exercise for the reader.

Part of what I found interesting about that exchange was that it shows that Scott, despite what is obviously his very high intelligence, doesn’t, perhaps can’t, think in mathematics. It is something I had once observed of another highly intelligent person, a past colleague. The next exchange is further evidence.

I'm sure you're aware that the share of income/wealth held by the bottom 90% is declining precipitiously compared to that held by the top 10%, especially in comparison to past eras. By my understanding this trend accelerated around the time trickle-down economics started.

I don't know at what time you think "trickle-down economics" started or even what you think it is. I believe the term was invented about eighty years ago by people on the left and attributed to people on the right.

I understand that correlation is not necessarily causation, but you have to admit that as far as empirical results go it's hard to imagine ones that would have supported the "trickle-down doesn't work" hypothesis more conclusively.

I assume the hypothesis is that rising incomes for high income people result in higher incomes for other people. You can't reject that by observing that incomes became more unequal. The question is whether incomes in lower parts of the distribution would have been higher or lower if something had prevented the rise in incomes at the higher part, which you have no evidence on.

Let me suggest an alternative explanation of the pattern you describe, the explanation that Charles Murray has been implying.3 On his evidence, people in the upper part of the income distribution continue to display roughly the same pattern of behavior that most of the population displayed in the post WWII period. Most people get married. Most stay married for long periods of time. Children are mostly raised by two parents. Most people get jobs, attempt to maintain careers, save money. But in the lower part of the distribution the pattern has shifted radically away from that. So we have a functional social structure at the high end, disfunctional at the low end.

I don't know if it is right but it makes more causal sense than "the rich got lots richer, the poor got only a little richer, and that must be because the rich were hogging all the money that otherwise would have gone to the poor," which does not have any obvious causal structure at all.

Let me offer a third explanation, based on data. From the end of WWII to the beginning of the War on Poverty, the poverty rate, definition held constant, fell sharply. Since the War on Poverty got fully funded and operating, the poverty rate, definition held constant, has been roughly fixed, going up and down with general economic conditions. That suggests that the expansion of the welfare state had the opposite of its intended purpose. It was supposed to get people out of poverty, to make them self-sustaining. It actually made poverty a little less unpleasant and so somewhat reduced the pressure to struggle out of it. As Murray describes in Losing Ground, the original purpose proved unachievable, so was abandoned.

And, for a fourth explanation having little to do with either side of political controversy, perhaps what happened was that as more and more low skilled jobs became doable by machinery, the premium to high intelligence, education, various related characteristics, rose. Putting claims in terms of wealth, especially if limited to things like stocks and bonds and doesn't include housing and pension funds, focuses attention on the very top of the distribution. I believe that if you look at income, it's not the multi-billionaires who drive the pattern but the doctors and lawyers and techies, of whom there are a lot more.

Scott sketches the argument that free exchange is always in the benefit of the parties starting with “In a free market, all trade has to be voluntary, so you will never agree to a trade unless it benefits you,” and responds:

This treats the world as a series of producer-consumer dyads instead of as a system in which every transaction affects everyone else.

I don’t know how much attention you have paid to price theory. In a simplified model (no externalities, public good problems, etc.) you really can treat the world that way because the net marginal effect of my transaction with you on third parties is zero. Most of the libertarians you are likely to encounter online are not trained in economics and couldn’t adequately explain the argument but their view is closer to correct than the view held by almost everyone who is neither a libertarian nor an economist, according to which the benefits and costs of ordinary market transactions go mainly to third parties. That’s the view that makes it natural to take it for granted that schooling should be provided for free because it makes people more productive or that buying a car made in America instead of one made in Japan makes Americans better off.

He answered:

I'm unclear what you mean to do by talking about how "in a simplified model (no externalities, public good problems, etc.) you really can treat the world that way". I agree that the only problem with that model is externalities, public goods, etc, which is why I'm focusing on them.

My point is that interdependence by itself doesn't prevent the simple libertarian model, in which each person controls his own life, from making sense. Absent economic theory it seems to prevent it, since I depend for what I do on interactions with lots of other people. Prices and property solve that problem because, in first approximation (ignoring the market failure problems), what I sell things for exactly measures their value to those who get them (price=Marginal value), the price I buy them for exactly measures the cost to the producer (price=marginal cost), so I am bearing the net costs of my life on others, receiving the net benefits of my life for others.

Just as if each person was entirely self sufficient, but in a complicated and interdependent world.

Beyond the first approximation the conclusion breaks down, for the sort of reasons you point out. It would in a self sufficient world too — the deer I shoot might be one you would have shot tomorrow. But considered as a mechanism for getting the right things to happen, for giving actors incentives compatible with the general welfare, it comes much closer than the political alternative, where individual actors bear almost none of the costs of their acts and receive almost none of the benefits.

A good deal of your argument consists of pointing out that there might be, probably have been, situations where particular government regulations did net good, which is true. But we don't have the option of only giving governments power to do good. In choosing among possible institutional structures, the question is whether, on net, government power makes us better off or worse off. You offer an a priori argument (market failure) for why the laissez-faire market that libertarians support sometimes produces a suboptimal outcome, one worse than what could be produced by a wise, benevolent, and all powerful philosopher king, which is correct. I offer an a priori argument for why the same logic that implies that also implies that the outcome produced by the political market will typically be farther from the optimal.

Scott wrote:

“As far as I know there is no loophole-free way to protect a community against externalities besides government and things that are functionally identical to it.”

Unfortunately, the statement is still true if you drop the last ten words.

[The FAQ was written more than a decade ago and some of Scott’s views have changed since. For a more recent version of his criticism of libertarianism (mine) see his review of The Machinery of Freedom.]

Mike Huben

Mike Huben was an active online critic of libertarianism on Usenet at least as early as the 1990’s; his site is no longer up but still accessible via the Wayback Machine. More than twenty years ago I wrote a response to his Non-Libertarian FAQ; here is a little of it. I have used boldface for parts of Mike’s argument intended as claims he is answering:

Mike wrote:

... public defenders, the Constitution and the Bill Of Rights, etc. all are government efforts that work towards defending freedoms and rights.

Mike omits to note that this part of his list consists almost entirely of government efforts to protect rights and freedoms from infringement by the government. It is rather as if we observed an unusually moderate thief, who had adopted a policy of never stealing everything his victim owned, and described his moderation as a private effort that worked towards defending property.

It would be foolish to oppose libertarians on such a mom-and-apple-pie issue as freedom and rights: better to point out that there are EFFECTIVE alternatives with a historical track record, something libertarianism lacks.

On the contrary, libertarianism, in its earlier and somewhat more moderate incarnation as classical liberalism, has a historical track record unmatched by any alternative in recorded history. That record includes the abolition of the slave trade, the institution of large scale free trade, the destruction of guild restrictions on employment — most of the progress of the 19th century, some of it reversed in the 20th.

If you don't pay your taxes, men with guns will show up at your house, initiate force and put you in jail.

This is not initiation of force. It is enforcement of contract, in this case an explicit social contract.

"Explicit social contract" presumably means "tax law passed by Congress." If I and my friends pass a law saying that Mike owes us tribute, will he then interpret our showing up at his front door, armed, to collect as merely enforcement of an explicit contract?

Or in other words, he is claiming that the obligation exists without having given us any good reason to believe it. Absent the obligation, the libertarian description of the process is correct. Mike begins to respond to these arguments in:

The constitution and the laws are our written contracts with the government.

There are several explicit means by which people make the social contract with government. The commonest is when your parents choose your residency and/or citizenship after your birth. In that case, your parents or guardians are contracting for you, exercising their power of custody. No further explicit action is required on your part to continue the agreement, and you may end it at any time by departing and renouncing your citizenship.

This assumes that the government already owns the country and thus has the right to require you to leave if you don't agree to the contract. Where did it get that right?

Immigrants, residents, and visitors contract through the oath of citizenship (swearing to uphold the laws and constitution), residency permits, and visas.

Again, this only works if the government already has the right to keep people out--which is one of the things you need the social contract to get. Otherwise the "contract" is void on grounds of duress.

My five year old occasionally decides that he is a toll gate and demands a penny toll for permitting me to go through a door or up the stairs. Suppose that twenty years from now, by which time he will be stronger and Mike feebler than they now are, he decides to do the same thing at Mike's front door when Mike is trying to come home — and charge a higher price. No policeman being in sight, Mike writes him a hundred dollar check, goes through the door, and calls up his bank to stop payment. Is Mike violating a contract? If not, how is an immigrant violating a contract when he decides not to pay taxes?

Some libertarians make a big deal about needing to actually sign a contract. Take them to a restaurant and see if they think it ethical to walk out without paying because they didn't sign anything.

The act by which one agrees to an implicit contract is an act that the other party has the right to control--in this case, coming into his restaurant and being served dinner. That leaves Mike with two alternatives:

A. It is proper to treat an act that you do not have the right to control as agreement to an implicit contract, without the other party's assent. That implies that you can impose a penalty (the amount you set as due on the contract) on that act, which amounts to controlling it.

B. The government has the same rights with regard to the territory of the U.S. that the restaurant owner has with regard to his food and restaurant. But that is the conclusion he wants to get from his argument, so starting with it makes his argument circular.

"Utopia is not an option."

This is the libertarian newspeak formula for overlooking problems with their ideas. Much like "Trust in Jesus". Used the way it commonly is, it means "libertarianism might do worse here: I don't want to make a comparison lest we lose."

I think I may have originated this phrase; in any case I am happy to defend it. Mike starts his discussion by criticizing libertarians for being utopians; he is now criticizing libertarians for not being utopians.

The implication of "Utopia is not an option" is "libertarianism might do worse here than a Utopia would, but since Utopia is not an option that does not imply that it does worse than some real world alternative would." It is a proper response to anyone who says (as many do) "under libertarianism bad result X will occur, therefore we should reject it," without offering an alternative set of institutions under which neither X nor some equally bad Y (that does not occur under libertarianism) would occur.

Someone else webbed a much longer reply to the same faq.

More generally, let U=A+Bln(I).

In Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960–2010. A NYT review.

Subscribe to David Friedman’s Substack

Ideas about a wide variety of subjects

The first of Scott's books that I read was The Art of Not Being Governed.

What struck me about it was that when I considered his model---people who don't want to be under the authority of a central government, who live in rough terrain where government forces can't easily go, and whose authorities are not political rulers but religious prophets---it seemed to me to be an equally good description of parts of the United States, particularly the Appalachian and Ozark regions. I don't think that Scott has ever suggested that the "hillbilly" archetype in American culture is an image of the stateless life, but a lot of its features could be fitted into his description.

For that matter, pre-monarchic Israel might be another example, though it's harder to be sure how people actually lived then; we have only one set of records, written by partisans of a different side, and some archaeological evidence that is hard to reconcile with those records.

Re Scott Alexander section:

The marginal utility of a dollar can (and I think does) also drop faster than the logarithm. From what I can see, the real problem with progressive taxation is that the utility function differs between people and isn’t really knowable. The basic logic is fine if we can make assumptions about the utility function. Which we can but I don’t trust anyone, let alone a politician, to do that. (I anyway favor a land tax.)

BTW I initially had difficulty understanding your point so I used ChatGPT to summarize then I reread it. Also your footnote was helpful.