TL;DR: The Government spent around $1.5 billion on emergency housing in the last five years and is now spending upwards of $7.1 billion a year on accommodation supplements, rent subsidies, first-home-buyer subsidies, motels, caravans and transitional housing. Stuff Federico Magrin

One argument given against fixing Aotearoa-New Zealand’s housing supply and demand crises to lower the most expensive housing costs in the world is that it would cost taxpayers too much and endanger the tax-free gains of the homeowners who decide election results. They argue higher or different taxes and more Government spending to increase housing supply or reduce population growth would cost taxpayers and businesses more overall in taxes, higher mortgage costs, lost leveraged and tax free gains in land values, and therefore cannot be justified.

Actually, not fixing our housing crises is already costing taxpayers $7.1 billion a year. Removing that cost could allow taxes to be cut and could supercharge economic growth.

It would be useful to reframe the housing debate as an opportunity to reduce taxpayer costs in the long run and to improve both productivity and labour supply for businesses as more locals can afford to train and stay here without the massive burden of the highest rent stress in the OECD. Effectively, there is a $7.1 billion fund already there to ‘pay’ to fix the crises. Or put another way, there is a $7.1 billion a year worth of payoffs to entice taxpayers to agree to fixes. (See more below the paywall fold, including The Kaka Project lens on the issue)

Elsewhere in the news this morning:

Family Planning clinic appointments are booked up months in advance because of staff shortages, especially in Wellington where the highest big-city rents in the country are forcing workers overseas or into higher-paid Te Whatu Ora jobs. Stuff Samantha Mythen

The number of decile 1 students in first-year tertiary study has halved since the Labour Government started its first-year fees-free policy, with students from wealthier backgrounds making up an increasingly greater share. NZ Herald-$$$ Derek Cheng

Australia is now rejecting 90% of the applications from Indian students for non-university courses there, cracking down on visa fraud and ‘ghost colleges’ to halve its migrant intake over the next 18 months. That is likely to increase pressure on applications from India for places in colleges here, and pose tough questions to the new National-ACT-NZ First Government, which is also looking at tightening migration settings at the same time as ramping up international education revenues for cash-strapped polytechnics and universities. SMH-$$$ Angus Thompson

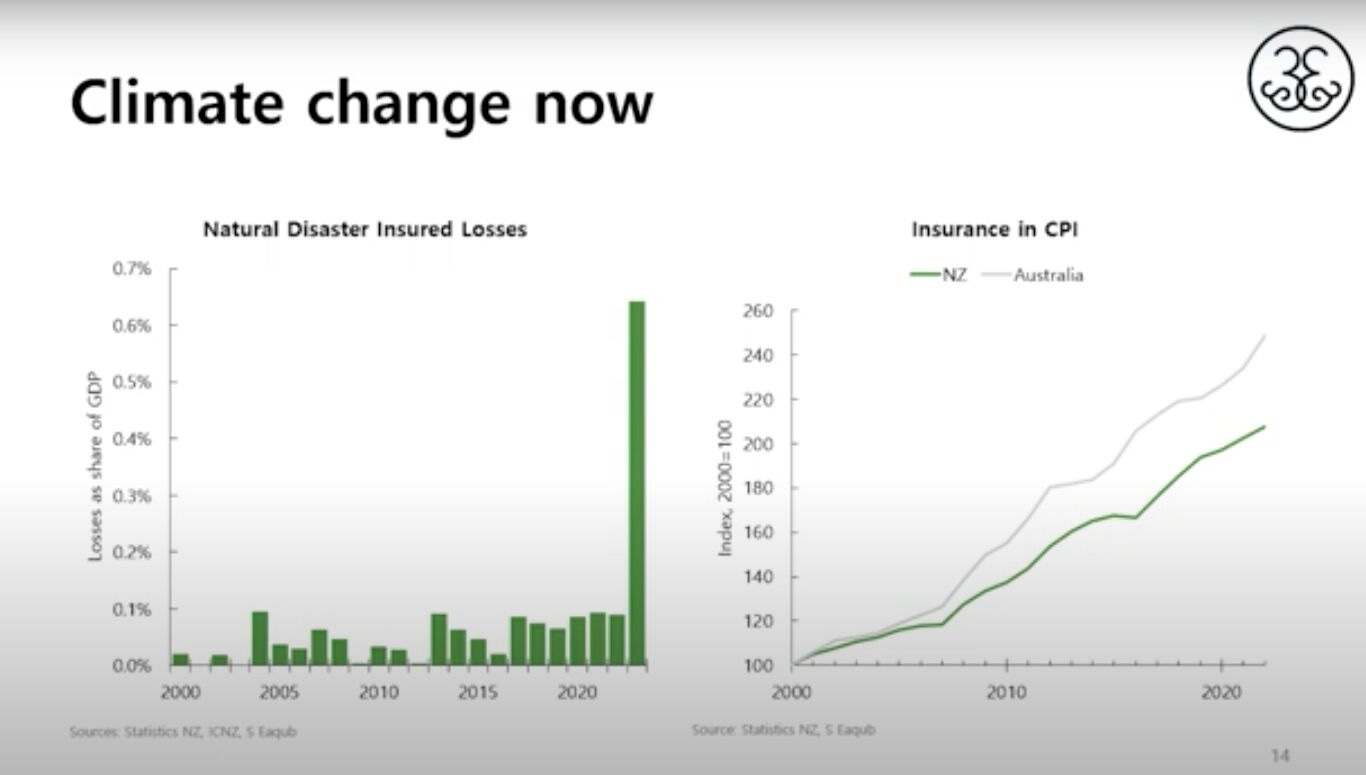

The Danube burst its banks overnight for the first time since 2013 as unusually warm winter weather melted snow and increased rainfall from climate change lifted river levels much higher than normal for this time of year. Reuters

Full paying subscribers can read and hear more detail in my Dawn Chorus podcast above and below the paywall fold. Join our community of paying subscribers to get access to ‘Hoon’ webinars, our private chat system and be able to comment on articles. Paying subscribers also support the public interest journalism we do at The Kākā on housing affordability, climate emissions and poverty.

$7.1b could be used & saved to fix our housing crises

Federico Magrin reports for Stuff this morning from data obtained under the OIA that the Ministry of Social Development spent $1.48 billion on emergency housing grants in the five years from 2018 to 2022.

That spending on motels, caravans, camp sites, camper vans and serviced apartments jumped from $52.42 million in 2018 to a peak of $374.17 million in 2022. In the nine months to the end of September 2023, emergency and transitional housing costs were $254.93 million, meaning annual spending was likely to be around $340 million for calendar 2023, down 9% from the 2022 peak, Magrin reported.

But that’s not the only cost to the Government of failing to fix our housing supply shortages, housing demand surpluses and brutally high housing costs. They are overflowing into every nook and cranny of our society and economy to:

squash productivity as workers are forced out of the biggest cities where agglomeration benefits accrue;

stunt skills growth as workers are forced to work to pay rents, rather than study or train;

push up emigration of residents forced to go overseas to find stable housing to start families; and,

escalate health, education and justice costs as rent stress, cold and mouldy housing and high private rental turnover rates increase transience in schools and hospital admissions for winter illnesses.

The $340 million a year also isn’t the only housing costs borne by the Government.

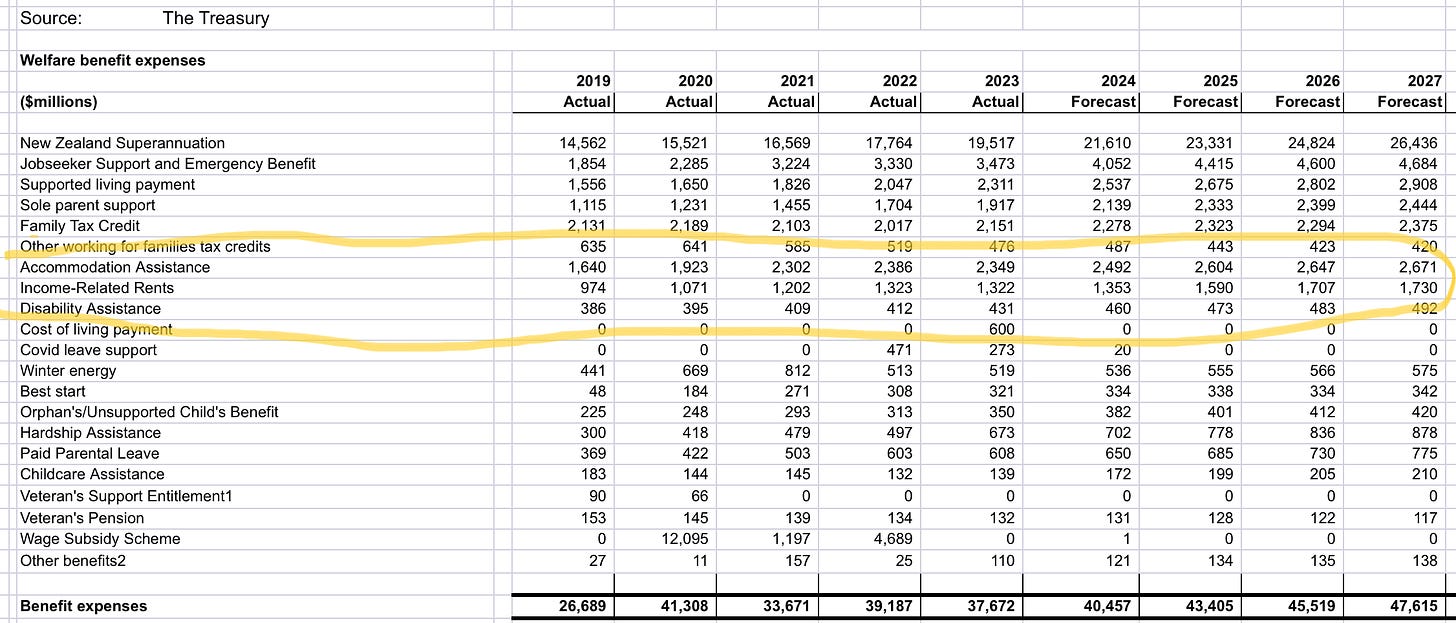

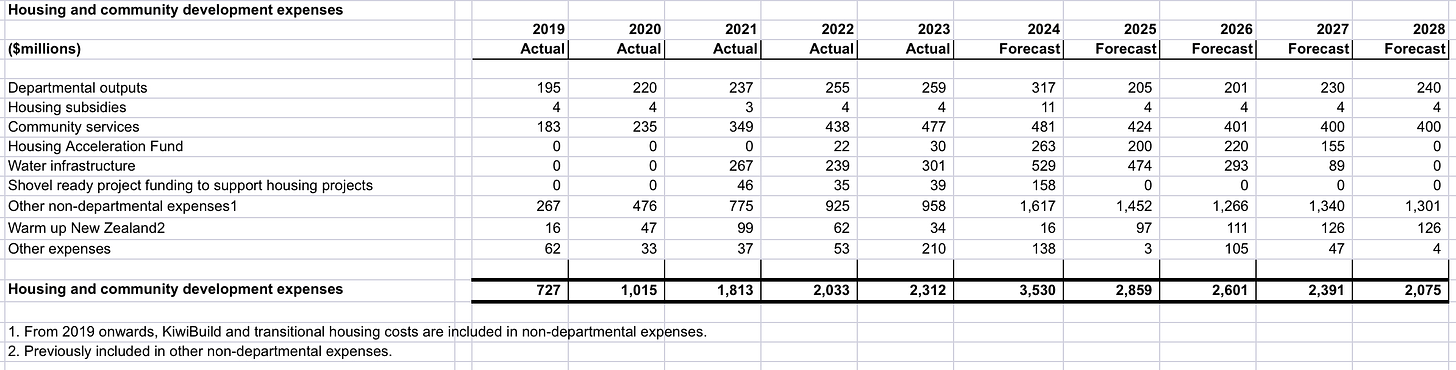

Here’s the two areas of spending, through ‘welfare’ and ‘housing and community services’, as reported in the just-published HYEFU and its data tables

Including accommodation supplements ($2.5 billion), income-related rents ($1.4 billion) and the non-departmental costs of housing and community development ($3.2 billion), total spending on housing in 2023/24 is forecast to mount up to $7.1 billion/year.

The Kaka Project Lens

That $7.1 billion could be used to justify investing both political and financial capital to solve the housing supply shortage and housing demand surplus.

For example, that $7.1 billion could be used to pay:

the interest costs on $160 billion of Government debt needed to pay for water, public transport and other infrastructure for hundreds of thousands of new or refurbished homes in the next 30 years;

for an income tax or GST cut to offset a $5 billion per year residential land levy of 0.5% on the current $1 trillion value of residential-zoned land; or,

to reinstate interest deductibility and building depreciation for residential and commercial landlords, along with removing all consenting and development contribution fees for developers in return for including inclusionary housing clauses.

The current Kaka Project proposal is for:

a broad-based and low-rate 0.5% affordable housing and climate levy on all residential land values (deferred to sale for cash-poor owners) to raise $5 billion a year to service $150 billion of new borrowing in 30 year bonds over the next 30 years for central and local government-funded water, public transport and housing infrastructure;

A bipartisan Affordable Housing and Climate Act that mandates housing and transport costs for the lowest quintile of earners to fall to less than 40% of disposable income by 2050 (it is currently well over 50%) and achieves zero transport and housing carbon emissions by 2050; and,

To achieve that bipartisan target in conjunction with an agreed population growth average limit over the next 30 years of 1.5-2.0% per year through skilled migration of workers and their families on work-to-residence visas, rather than temporary visas (population growth through temporary worker migration averaged 1.5-2.0% over the last 20 years).

The political economy of such an Act

Agreeing an Affordable Housing and Climate Act would require some kind of ‘grand coalition’ or deal that satisfied the aims of the major parties and the minor parties likely to form Government over that 30 year period. This has been done before in the form of the agreements to pass and keep the State Sector Act (1988), the Reserve Bank (1989) Act, the Resource Management Act (1991) and the Public Finance Act (1989). They form the foundation of our current Government and economy, limiting housing and infrastructure development on the bipartisan assumptions of less 0.5%/year population growth and limits on the size of Government taxation, spending and net debt of no more than 30% of GDP.

An Affordable Housing and Climate Act would have to create a ‘new deal’ based on a reframing of the current debates, where the various parties get most of what they want and have to give up some other things.

My suggestions for such a ‘new deal’ could include:

agreeing no more long-term and multi-billion-dollar public transport or motorway projects in exchange for repurposing some existing road lanes and public land for busways, cycleways and pathways that enable massive zero-carbon medium-density joint housing and commercial developments in our seven biggest and fastest growing Auckland, Hamilton, Tauranga, Wellington, Christchurch, Queenstown and Dunedin;

removing all consenting and development contribution fees for certified zero-carbon developments using Government-insured and guaranteed building plans and materials in exchange for full Government-debt-funded water/transport/housing/health/education infrastructure development to support these plans and ensure councils don’t have to increase their own debt or rates;

agreeing to reinstate interest deductibility and building depreciation for rental and commercial property investors, while leaving in place the tax-free nature of capital gains to incentivise the building of shareholder value through business values, rather than land values, in exchange for the residential land value levy;

agreeing not to tax earnings inside KiwiSaver and other funds that can’t be accessed until the age of retirement, which would encourage households in funds investing in real businesses and infrastructure, rather than land;

agreeing to create an independent Government authority mandated to achieve the Affordable Housing and Climate Act’s limits on housing and transport affordability, zero carbon and population growth, or for their leaders to be dismissed, similar to the Reserve Bank Act;

giving that authority the power in conjunction with councils and iwi to consent any development that furthers the achievement of those limits by default; and,

linking the achievement of the Affordable Housing and Climate Act limits to reduction in income, corporate and/or GST rates, and/or introducing wage indexation to income tax thresholds over time.

In summary, this bipartisan ‘new deal’ focused around a Reserve Bank-style Affordable Housing and Climate Act would;

completely change the incentives households, businesses, councils and the Government currently have to block new housing developments or any infrastructure developments that might increase debt, interest rates or rates, or endangers the current exemption from taxes on capital gains on land values;

completely change the incentives for households, businesses, councils, the Government and median voters have towards investing in public infrastructure, business technology and business development in ways that supercharge productivity growth and real wage growth in ways that prioritise real nominal GDP per capita growth over nominal total GDP growth and tax-free land value growth; and,

create an agreed pathway for fast growth and development that underwrote business development and planning and focused councils, the Government and median voters on improving housing affordability, raising real wages and hitting our emissions reduction targets in exchange for agreed cuts in income and/or consumption taxes, removing development and consenting fees and incentivising hundreds of billions of dollars worth of household savings for investment in businesses and infrastructure, rather than dead land values.

There is also another ‘fund’ that could be used to pay for this ‘new deal’. The international emissions credits that both National and Labour plan to buy to meet our Paris Agreement targets could cost up to $24 billion, representing a liability in the Crown’s accounts that has to be paid for over time or reduced through other means. Reducing emissions through housing and public transport investment could be paid for by reducing this liability.

The two chunks of reduced government spending (and therefore future tax reductions) if the housing and climate crises are solved add up to nearly $80 billion in total over the next six years, or over $13 billion per year.

I welcome challenges, unintended consequences and additions/deletions in the comments below.

Quote of the day

“If we look at the bigger picture, we can see that winter precipitation is growing and with the rise of temperatures we will see less snowfall plus it can melt earlier.” Climate researcher Anna Kis, who works for the “1.5 degrees” climate project, on the River Danube breaking its banks. Reuters

Chart & video of the day

The weather was very bad this year

Cartoon of the day

All the feels

Timeline cleansing nature pic of the day

A very camouflaged caterpillar

Ka kite ano

Bernard

PS: I’ll publish these occasionally through until January 15, when I’ll resume publication in full. I’m conscious our subscriber numbers stalled last summer when I took a full three weeks off, and they stalled again towards the end of this year as I took a higher share of articles out from behind the paywall. I’ve found regular and frequent posts and podcasts, most of which are behind paywalls, helps keep our community growing. I welcome appeals to open up the particularly public-interestey ones.

Dawn Chorus for Friday, December 29