Highlights From Warren Buffett’s 2016 Letter to Shareholders

“Today, I would rather prep for a colonoscopy than issue Berkshire shares.”

“Today, I would rather prep for a colonoscopy than issue Berkshire shares.”

— Warren Buffett, 2016 letter to shareholders

Introduction

The last Saturday in February has become something of a ritual for Berkshire Hathaway shareholders as well as many other interested observers. Some have likened it to “Christmas morning” for capitalists!

While this has “cult-like” overtones, the release of Warren Buffett’s annual letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders is rightly regarded as a major event for anyone interested in business. This is mainly because Mr. Buffett does not restrict the scope of his commentary to Berkshire’s results but also opines on a wide variety of topics of general interest. In a format lending itself to greater depth than a television interview, we are offered an opportunity to see Mr. Buffett reveal some of his cards.

This article presents selected excerpts and commentary on a few of the important subjects directly related to Berkshire but is not an all encompassing review of the letter, especially as it relates to commentary on general business conditions in the United States. Everyone is going to take away something different from reading the letter and it is important to spend some time looking at the actual document before reading the opinions of others, or even reading selected excerpts. This is particularly true for shareholders who should look at business results with fresh eyes rather than to allow others to direct them to what is important.

Read Warren Buffett’s 2016 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders

Berkshire’s Intrinsic Value

Longtime observers of Berkshire Hathaway know that Mr. Buffett does not comment specifically on the company’s intrinsic value. This is entirely appropriate for a number of reasons. If you take two informed individuals and ask them to judge the intrinsic value of any business, it is very unlikely that the estimates will match exactly. What we should want from a CEO is an assessment of the fundamentals. As shareholders, we are responsible for determining our own estimates of intrinsic value. That being said, Mr. Buffett does provide some important commentary regarding intrinsic value as well as clear indications of his view of intrinsic value relative to book value.

At the beginning of the letter, Mr. Buffett comments on how Berkshire’s book value was a reasonably close approximation for intrinsic value during the first half of his 52 year tenure. This is because Berkshire was dominated by marketable securities that were “marked to market” on Berkshire’s balance sheet. However, by the early 1990s, Berkshire shifted its focus to outright ownership of businesses. The economic goodwill of acquired businesses that show poor results are required to be written down based on GAAP accounting. In contrast, the economic goodwill of successful acquisitions are never “marked up” on the balance sheet. This causes a growing gap between book value and intrinsic value given that most, but not all, of Berkshire’s acquisitions have turned out well:

We’ve experienced both outcomes: As is the case in marriage, business acquisitions often deliver surprises after the “I do’s.” I’ve made some dumb purchases, paying far too much for the economic goodwill of companies we acquired. That later led to goodwill write-offs and to consequent reductions in Berkshire’s book value. We’ve also had some winners among the businesses we’ve purchased – a few of the winners very big – but have not written those up by a penny.

We have no quarrel with the asymmetrical accounting that applies here. But, over time, it necessarily widens the gap between Berkshire’s intrinsic value and its book value. Today, the large – and growing – unrecorded gains at our winners produce an intrinsic value for Berkshire’s shares that far exceeds their book value. The overage is truly huge in our property/casualty insurance business and significant also in many other operations.

What we can take away from this brief discussion is that the gap between Berkshire’s book value and intrinsic value has grown over time and, with additional successful acquisitions, should continue to grow in the future. To be clear, important aspects of Berkshire’s results will show up in book value in the future. Berkshire’s retained earnings are fully reflected in book value. Additionally, changes in the value of marketable securities (with few exceptions) are also reflected in book value, net of deferred taxes. However, to the extent that the economic goodwill of Berkshire’s wholly owned subsidiaries continue to increase, the gap between book value and intrinsic value will continue to grow.

Repurchases and Intrinsic Value

The discussion of intrinsic value, and the growing gap between book value and intrinsic value, brings up an interesting point that we have identified several times in the past. Berkshire Hathaway has an unusual policy of declaring, in advance, the maximum price that it is willing to pay to repurchase shares. When the repurchase program was initially created in September 2011, the limit was 110 percent of book value. In December 2012, the limit was increased to 120 percent of book value in order to facilitate the repurchase of 9,200 Class A shares from the estate of a long-time shareholder. The repurchase limit has remained constant ever since and Berkshire has not been able to repurchase any material number of shares despite a few occasions where the share price almost fell to 120 percent of book value.

Mr. Buffett continued to defend the repurchase limit while acknowledging that repurchasing shares has been hard to accomplish:

To date, repurchasing our shares has proved hard to do. That may well be because we have been clear in describing our repurchase policy and thereby have signaled our view that Berkshire’s intrinsic value is significantly higher than 120% of book value. If so, that’s fine. Charlie and I prefer to see Berkshire shares sell in a fairly narrow range around intrinsic value, neither wishing them to sell at an unwarranted high price – it’s no fun having owners who are disappointed with their purchases – nor one too low. Furthermore, our buying out “partners” at a discount is not a particularly gratifying way of making money. Still, market circumstances could create a situation in which repurchases would benefit both continuing and exiting shareholders. If so, we will be ready to act.

The signaling effect of Berkshire setting the repurchase limit at 120 percent of book value has clearly limited the opportunity to actually repurchase shares and has made many shareholders, including some very prominent hedge fund managers, view this level as a floor which is something we have consistently disagreed with. Mr. Buffett once again reiterates that shareholders should not misinterpret the purpose of the repurchase limit:

The authorization given me does not mean that we will “prop” our stock’s price at the 120% ratio. If that level is reached, we will instead attempt to blend a desire to make meaningful purchases at a value-creating price with a related goal of not over-influencing the market.

It is clear that Mr. Buffett regards Berkshire’s intrinsic value as far exceeding the 120 percent of book value limit and he has said so numerous times. Interestingly, he has also given us a clue regarding what he thinks is above Berkshire’s intrinsic value: 200 percent of book value. The following excerpt is taken from Mr. Buffett’s 2014 letter to shareholders:

If an investor’s entry point into Berkshire stock is unusually high – at a price, say, approaching double book value, which Berkshire shares have occasionally reached – it may well be many years before the investor can realize a profit. In other words, a sound investment can morph into a rash speculation if it is bought at an elevated price. Berkshire is not exempt from this truth. Purchases of Berkshire that investors make at a price modestly above the level at which the company would repurchase its shares, however, should produce gains within a reasonable period of time. Berkshire’s directors will only authorize repurchases at a price they believe to be well below intrinsic value. (In our view, that is an essential criterion for repurchases that is often ignored by other managements.)

So, there we have it: Mr. Buffett considers 120 percent of book value, and levels modestly above it, to be likely to produce gains for buyers within a reasonable period of time (but still several years) whereas buying at a high level like 200 percent of book value could result in a very extended period of time before a profit can be realized.

As of December 31, 2016, Berkshire’s book value per Class A share was $172,108. Class A shares closed at $255,040 on Friday, February 24. This indicates that shares currently trade at 148 percent of book value. This seems to be more than “modestly above” Berkshire’s repurchase limit, but well below the clear danger level of 200 percent of book. Is 148 percent of book value a close approximation of intrinsic value? A good level to buy shares? Or a good level to sell? Shareholders cannot expect to be spoon fed an answer by Mr. Buffett and must decide for themselves.

Berkshire’s 21st Century Transformation

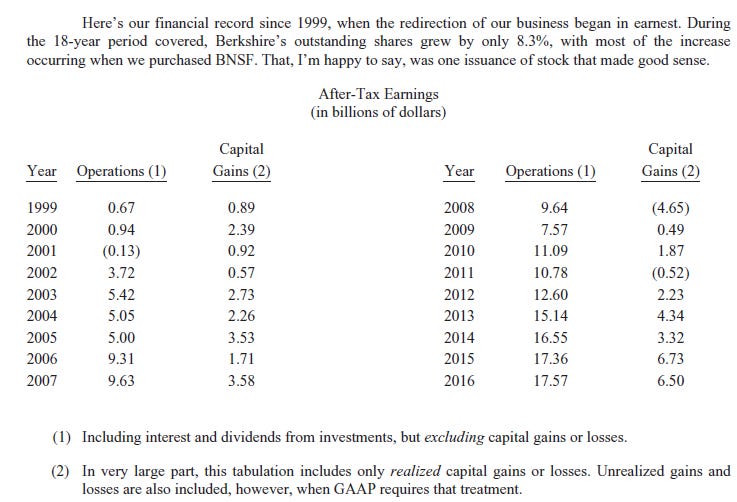

A shareholder considering Berkshire Hathaway as an investment opportunity today faces a radically different company than what existed at the turn of the century. As Mr. Buffett notes early in the letter, the second half of his tenure has been characterized by the growing importance of controlled operating companies. The effect of this transformation can be clearly seen in a chart of after-tax earnings since 1999:

Sometimes, long term trends are not readily apparent to those who are observing changes on a year-to-year basis. What is clear, however, when looking at the table above is that Berkshire is a far different company today compared to 1999. Furthermore, this trend is likely to accelerate significantly in the future, especially if Berkshire intends to retain all or most of its earnings. As we discussed last year, Berkshire in 2026 is going to look radically different than it does today. However, we do not know what shape it will necessarily take, other than to note that a major recession is likely to help Berkshire substantially when it comes to capital allocation:

Every decade or so, dark clouds will fill the economic skies, and they will briefly rain gold. When downpours of that sort occur, it’s imperative that we rush outdoors carrying washtubs, not teaspoons. And that we will do.

What Mr. Buffett believes to be an advantage for individual investors with the right temperament is even more of an advantage for Berkshire given the company’s ability to accomplish very large transactions quickly during times of economic distress:

During such scary periods, you should never forget two things: First, widespread fear is your friend as an investor, because it serves up bargain purchases. Second, personal fear is your enemy. It will also be unwarranted. Investors who avoid high and unnecessary costs and simply sit for an extended period with a collection of large, conservatively-financed American businesses will almost certainly do well.

Berkshire today has significant excess capital available for deployment but the level of exuberance in capital markets is quite high so we have seen cash continue to build up. Mr. Buffett is 86 years old and apparently has no plans to retire anytime soon. With some good fortune, he may still be at the helm during the next major economic downturn. From the perspective of Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, the continued retention of earnings and build up of cash makes sense primarily because we are increasing the options available to Mr. Buffett if opportunities arise during his remaining years running Berkshire.

Non-GAAP Accounting

Journalists seeking a “gotcha” story have sometimes identified Berkshire’s treatment of amortization of intangible assets as fertile ground for charges of hypocrisy. This is because Mr. Buffett has frequently criticized the use of non-GAAP accounting measures at other companies.

In Berkshire’s presentation of the results of certain operating subsidiaries, the amortization of intangible assets is excluded and instead presented as an aggregate figure. This appears to be done for two primary reasons: First, the presence of intangible amortization is a function of Mr. Buffett’s capital allocation decisions rather than the underlying ability of subsidiary managers to generate returns on the actual tangible capital they are working with. Second, much of the intangible amortization is not really an economic cost from Mr. Buffett’s perspective. Indeed, some of the intangibles are likely to be appreciating in value over time rather than depreciating.

For several years I have told you that the income and expense data shown in this section does not conform to GAAP. I have explained that this divergence occurs primarily because of GAAP-ordered rules regarding purchase-accounting adjustments that require the full amortization of certain intangibles over periods averaging about 19 years. In our opinion, most of those amortization “expenses” are not truly an economic cost. Our goal in diverging from GAAP in this section is to present the figures to you in a manner reflecting the way in which Charlie and I view and analyze them.

On page 54 we itemize $15.4 billion of intangibles that are yet to be amortized by annual charges to earnings. (More intangibles to be amortized will be created as we make new acquisitions.) On that page, we show that the 2016 amortization charge to GAAP earnings was $1.5 billion, up $384 million from 2015. My judgment is that about 20% of the 2016 charge is a “real” cost. Eventually amortization charges fully write off the related asset. When that happens – most often at the 15-year mark – the GAAP earnings we report will increase without any true improvement in the underlying economics of Berkshire’s business. (My gift to my successor.)

Mr. Buffett goes on to point out that, in some cases, GAAP earnings overstate economic results. For example, depreciation in the railroad industry regularly understates the actual cost of maintenance capital expenditures required to prevent deterioration of the system.

Are the charges of hypocrisy valid? We should want managers to present results according to GAAP (which Berkshire does within its financial statements) and to also point out important factors that might cause investors to make appropriate adjustments. This requires both trust in management’s honesty and the ability of investors to bring to bear appropriate analytical abilities to judge the situation for themselves. We do not have to blindly trust Mr. Buffett’s statement on intangibles. We can see the results of the business operations over time and attempt to evaluate whether intangible amortization makes any sense in light of results. Viewed in this manner, Berkshire’s supplemental presentation seems both useful to shareholders and reflective of economic reality.

In contrast, many companies use non-GAAP measures for purely self-serving purposes, as Mr. Buffett goes on to describe in some detail:

Too many managements – and the number seems to grow every year – are looking for any means to report, and indeed feature, “adjusted earnings” that are higher than their company’s GAAP earnings. There are many ways for practitioners to perform this legerdemain. Two of their favorites are the omission of “restructuring costs” and “stock-based compensation” as expenses.

Charlie and I want managements, in their commentary, to describe unusual items – good or bad – that affect the GAAP numbers. After all, the reason we look at these numbers of the past is to make estimates of the future. But a management that regularly attempts to wave away very real costs by highlighting “adjusted per-share earnings” makes us nervous. That’s because bad behavior is contagious: CEOs who overtly look for ways to report high numbers tend to foster a culture in which subordinates strive to be “helpful” as well. Goals like that can lead, for example, to insurers underestimating their loss reserves, a practice that has destroyed many industry participants.

Charlie and I cringe when we hear analysts talk admiringly about managements who always “make the numbers.” In truth, business is too unpredictable for the numbers always to be met. Inevitably, surprises occur. When they do, a CEO whose focus is centered on Wall Street will be tempted to make up the numbers.

Those of us who read earnings results routinely know that the types of “adjustments” Mr. Buffett refers to are more the norm than the exception. The idea that items that recur every single quarter should be excluded from earnings is obviously absurd, but this is how managers are evaluated by the investment community. Stock based compensation is almost always excluded from “adjusted” figures as if dilution is irrelevant (or, worse, doesn’t matter because the company is blindly repurchasing shares at any price to offset the dilution). Many companies, including some Berkshire investees, announce restructuring activities on a routine basis and either exclude them entirely from non-GAAP numbers or report these costs as a separate corporate line item that is unallocated to business segment results.

Will Mr. Buffett’s admonishments have any effect whatsoever on the behavior of managers or the blind willingness of the analyst community to accept non-GAAP numbers at face value? The answer is likely to be no.

Investment Portfolio

Although Mr. Buffett does not discuss Berkshire’s equity investment portfolio in much detail, there are a couple of notable items that deserve investor attention:

Berkshire’s investment in Kraft Heinz is accounted for by the equity method and is not carried on Berkshire’s balance sheet at market value, unlike most equity investments that are regularly marked-to-market. As a result, Berkshire’s 325,442,152 shares of Kraft Heinz are carried by Berkshire at $15.3 billion but had a market value of $28.4 billion at the end of 2016. This $13.1 billion in unrecorded market value is worth an incremental $8.5 billion in book value for Berkshire after accounting for deferred taxes at an approximate 35 percent tax rate. It is probably a good idea to adjust Berkshire’s reported book value by adding this $8.5 billion.

Berkshire owned $7.1 billion of Apple stock at the end of 2016. There has been much speculation regarding whether this position was purchased by Mr. Buffett or by Berkshire’s two investment managers, Todd Combs and Ted Weschler. Mr. Buffett provides a clue: Mr. Combs and Mr. Weschler manage a total of $21 billion for Berkshire which includes $7.6 billion of pension assets not included in the figures reported for Berkshire. Accordingly, they control about $13.4 billion of Berkshire’s portfolio reported in the letter and annual report. While it is not impossible that the entire Apple position can be attributed to Mr. Combs and Mr. Weschler, it would have to account for more than half of their combined portfolio. This seems unlikely. We would infer that Mr. Buffett is responsible for at least part of Berkshire’s position in Apple.

Are Berkshire’s positions in marketable securities “permanent”? Many are held with no predefined “exit” date, but Berkshire reserves the right to sell any security at any time:

Sometimes the comments of shareholders or media imply that we will own certain stocks “forever.” It is true that we own some stocks that I have no intention of selling for as far as the eye can see (and we’re talking 20/20 vision). But we have made no commitment that Berkshire will hold any of its marketable securities forever.

Confusion about this point may have resulted from a too-casual reading of Economic Principle 11 on pages 110 – 111, which has been included in our annual reports since 1983. That principle covers controlled businesses, not marketable securities. This year I’ve added a final sentence to #11 to ensure that our owners understand that we regard any marketable security as available for sale, however unlikely such a sale now seems.

While it is best to not read too much into this statement, we should keep it in mind the next time media reports appear regarding Berkshire’s “permanent” ownership of stocks like Coca-Cola and Wells Fargo. Indeed, the lack of any mention of the recent Wells Fargo scandal in Mr. Buffett’s letter coupled with this very clear statement could be viewed as a message to managers of portfolio companies.

There are many other important topics in the letter including a lengthy discourse on the merits of passive investment for the vast majority of individuals and institutions. Readers are encouraged to review the entire letter in full and to view the excerpts and commentary in this article as only a starting point.

Disclosure: Individuals associated with The Rational Walk LLC own shares of Berkshire Hathaway.

Subscribe to The Rational Walk

The Rational Walk publishes articles about a wide range of topics including business, politics, investing, personal finance, history, philosophy, and books.