Discover more from Exploring Church History

A Review of Mark Noll, In the Beginning Was the Word: The Bible in American Public Life

Living in what some call a post-Christian society, one might expect the Bible to have receded from public life by this time. While it might still have some influence in small enclaves of believers, it would rarely be seen in the public discourse. And to some degree this is true. Yet even in recent presidential campaigns and inaugural addresses, the Bible still shows up. Its lingering influence points to a long, complex history of the Bible’s place in American public life.

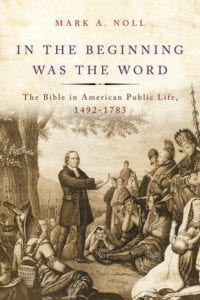

Eminent religious historian Mark Noll traces the early part of this history in his book In the Beginning Was the Word: The Bible in American Public Life, 1492–1783 (Oxford University Press, 2016; source: publisher). So much could be said about the Bible in America, and Noll seeks to narrow his discussion by focusing on how the Bible influenced public life—that is, “to show how such influences shaped the history of Scripture for political, imperial, and national purposes” (5).

As one expects from Noll, he provides a very readable account of how Americans used the Bible in public discourse. Inevitably, he must be selective, and many aspects of the history of biblical interpretation stand beyond the scope of the volume (e.g., exploring debates over principles of exegesis, examining shifts in the commentarial tradition). But his selections form a coherent tale that illuminates the shifts within the increasingly sticky relationship between the Bible and politics. Noll gives us an overarching view of the story of the Bible in American public life and provides insightful historical analysis along the way.

To give a taste of Noll’s historical analysis, I want to focus on a handful of themes that he emphasizes in his book. First, a central topic of the volume is the Bible’s relationship to Christendom—that is, the structuring of society through a church-state establishment. To this end, Noll roots his history in the rise of Protestantism. While Luther, Calvin, and other reformers pledged allegiance to the Bible as their greatest authority, they nonetheless saw no contradiction between sola scriptura and a church-state establishment. Thus, as Bible-devoted Puritans migrated to the New World, they sought to build states on the teachings of the Bible, just as English Puritans sought to do in the Interregnum period in England. Both political ventures eventually failed, but while Oliver Cromwell’s Bible-based Christendom spelled the end of the Bible’s influential reign in England, the lack of a militaristic conflagration in New England allowed the Bible to continue exerting influence even after the Bible-based state had waned. That is to say, when Americans built an entirely new political nation in the United States, they found ways to keep the Bible central that the British did not. In short, this book traces the survival of the Bible’s influence in America in the wake of Christendom’s doom.

A second theme of the book is the rise and influence of biblicism, which Noll defines as “an effort to follow ‘the Bible alone’—absent or strongly subordinating other authorities—as the path of life with and for God” (8). While the notion of sola scriptura reaches back to the Reformation era, Noll differentiates between what the reformers understood as “the Bible supreme” and what later Protestants took to mean “the Bible only.” Holding to “the Bible only” freed Protestants at first from the authority of what they deemed to be a corrupt church. But it later freed them from all kinds of authorities and even limited Protestant churches in controlling their people. Unmoored from an authoritative structure, the Bible became an unwieldy instrument in the hands of people who often used it for their own purposes.

In this vein, it is perhaps worth mentioning that Noll, who affirms “the Bible as definitive divine revelation,” lays out this history in such a way that will make some who share his high view of the Bible squirm (4). For such evangelicals, Noll calls this story “a cautionary tale” (4). He seeks to show how this devotion to the principle of “the Bible only” accomplished both good and evil. For example, not only did the Bible deepen as it enabled African American slaves to find the hope of new life both in this world and in the world to come, but the Bible also thinned as the Bible-only principle allowed others to defend race-based slavery and imperial policies in the interest of economic gain.

Related to the theme of biblicism is a third theme: democratization. On the one hand, the Bible had a democratizing effect on readers, particularly through the new access that readers had to the Bible in their language. The mid-eighteenth-century revivals likewise encouraged those from below to read and even preach the Bible, giving those who traditionally lacked power new opportunity and influence. On the other hand, these new readers democratized the Bible, making it their own and using it to defend views that often diverged one from another. Interestingly, the versification of Scripture in the mid-sixteenth century facilitated democratization because it made it easier for various readers to proof-text in order to support their positions against theological—and political—opponents.

Connected to democratization is a fourth theme, namely, that the Bible was interpreted in diverse—even opposing—ways in American public life. Examples abound, including debates over Anne Hutchinson’s interpretation of the Bible, over religious freedom in Rhode Island and Pennsylvania, over slavery, over revival, and over the patriot cause. This final issue presents a striking picture of divergent views, since both patriots and loyalists defended their views by recourse to the Bible. Here Noll observes that those who claimed devotion to “the Bible only” sometimes used the Bible for their own purposes rather than letting the Bible guide them.

Together these themes highlight an undercurrent that flows throughout the book: the question of authority. A Protestant monk in Germany questioned the authority of the Roman Catholic Church; a dissenting voice resisted the Congregational establishment in Massachusetts; an African American asserted the injustice of slavery in a slave-based economy; a woman exercised influence by leading Bible studies in a paternalistic community; a patriot defended all-out rebellion against the British crown—and all did so by arguing from the Bible.

In all these and other cases, this book reminds us that the question of who or what holds ultimate authority—whether the state, the church, the Bible, or the individual with his or her right of private judgment—has far-reaching consequences for how a society structures itself. Noll thus highlights a corollary question on authority, namely, “the persistent Protestant dilemma of supreme trust in Scripture accompanied by divergent interpretations of Scripture” (322). And he underscores that while trust in the Bible as one’s only authority brought about some good results, it “did not guarantee positive benefits for that influence in society” (4).

In my view, this descriptive approach has much to commend it, especially from the perspective of historical analysis. At the same time, it also raises a number of theological questions that go unanswered in the volume. Why doesn’t the Bible uniformly affect its readers? What does the divergence in interpretation say about the nature, perspicuity, and authority of Scripture? How should one—like Noll—uphold the Bible as “definitive divine revelation” (4) in light of divergent interpretations among Christians?

This review lacks the space to answer these questions, though theologians have offered helpful considerations in response—such as the notions that the nature of fallen humanity makes interpreters fallible, that the visible church includes both true believers and false professors, that even some Protestants believe Scripture is best interpreted within the church, and that there are better and worse methods of interpreting Scripture. Understandably, Noll’s primary aim is historical, not theological, and thus he cannot be expected to explore these questions in depth. They do, however, merit further discussion.

At least one way that Noll does helpfully qualify the picture of divergent interpretations is to note that some used the Bible as a “didactic authority” while others used it rhetorically to promote their causes (327). Here he clearly recognizes that not all interpretations are equal, rejecting an all-out relativistic assessment of Bible interpretations.

Bearing these theological thoughts in mind, the historical themes in Noll’s book highlight well that the way some Americans have cast the sola scriptura principle as “the Bible only” does not always remain faithful to Scripture and can even bring about negative results in society. Noll also does a commendable job of including diverse voices in his history of the Bible, avoiding a merely white, elitist account. In addition, he details the changes in how people approached the Bible by rooting the story in the Protestant Reformation and tracing both Christendom’s demise and democracy’s rise, revealing much about the lingering views of the Bible in our world today. And this book also reminds us that throughout early American history, the Bible loomed large at every turn—a history of America, therefore, is incomplete without a history of the Bible in America.

But In the Beginning Was the Word only tells part of the story. While the Bible, as we noted earlier, bears some influence in public discourse today, it does not carry the same degree of influence as it did in the colonies or in the Revolution. How did that influence wane? It did not, of course, immediately leave the scene once the states ratified the Constitution. And a second book from Noll is in the works that will carry the story into the early decades of the Republic to tell how the new nation appropriated the Bible apart from the structure (and strictures) of Christendom but ultimately failed in realizing its expansive vision for the United States. That volume is sure to be a welcome addition to our understanding of the important history of the Bible in America.

*Full Disclosure: I received a complimentary copy of this book from the publisher in exchange for my honest review.

Subscribe to Exploring Church History

A home for my musings on history, theology, and culture