Last week, I shared an extract from a chapter-in-progress about prose poetry in the 1990s:

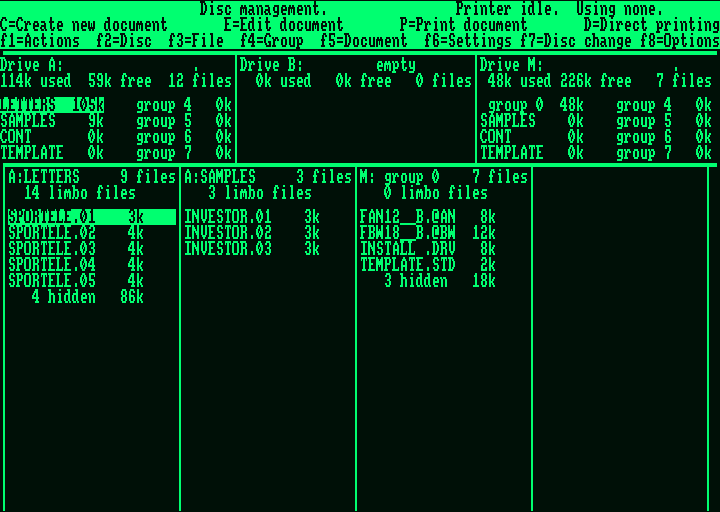

I’m finding the Nineties a fascinating decade to write about, partly because it was when I discovered poetry as a teenager, which means researching it has led to leafing through old magazines in my loft. And this has got me thinking of Nineties literary culture as a time between paper and screen, when reading and writing were still primarily offline activities, but increasingly moving to what David Kinloch described — in a prose poem from 1992 — as the “green loom” of an early word processor.

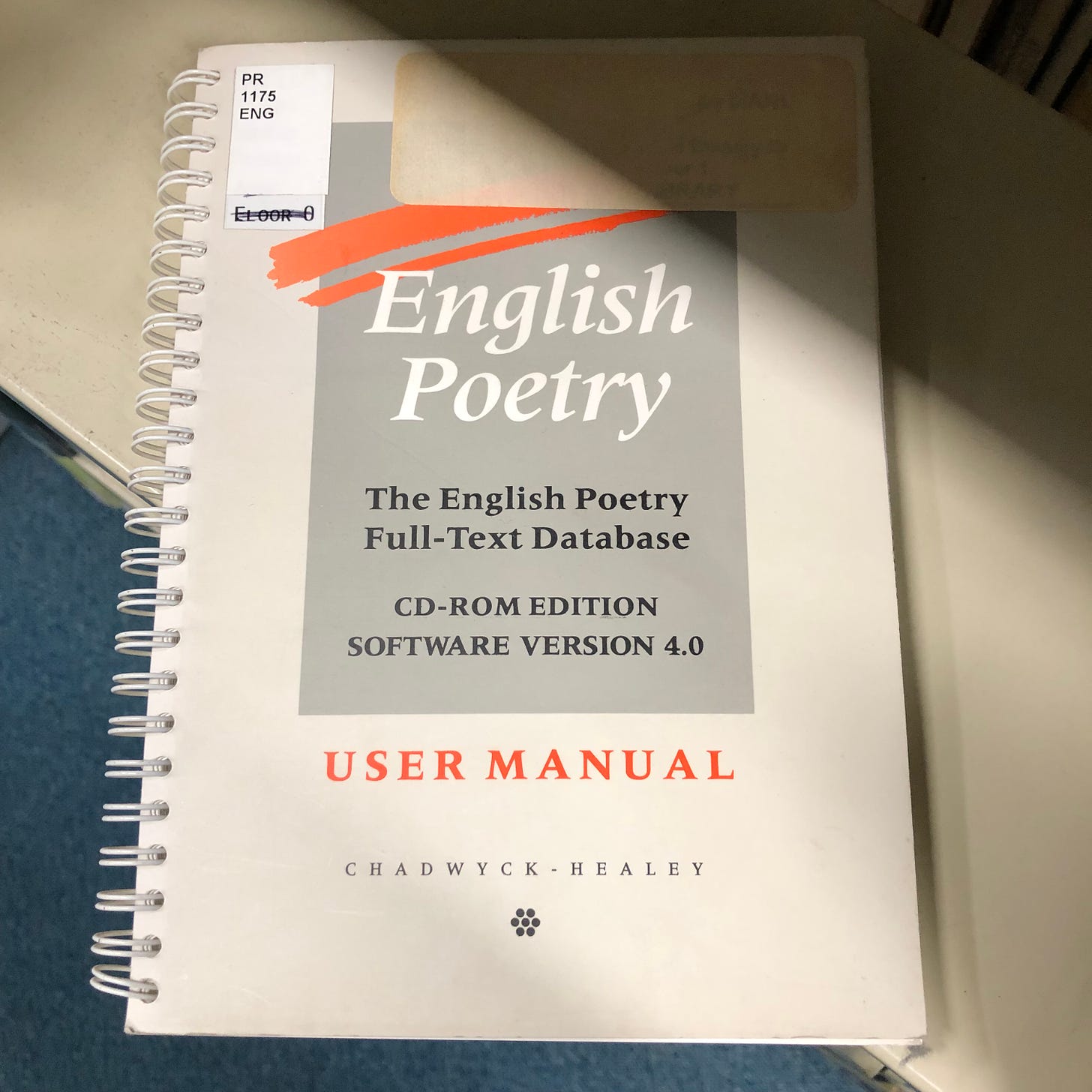

Here are some of the millennium-bugs-in-amber that I’ve uncovered, including a programme to improve your formalism and a found poem from a user manual. Feel free to post your memories below — did you research the word “love” using the English Poetry CD-ROM? — but please remember to observe Netiquette* at all times!

* “Good manners on the Internet” — Poetry Review (Spring 1995)

On the computer screen, it looks like a sort of oddball word-processor. The writing area is a field of numbered blank lines. Above it is a row of dots and dashes representing whatever rhythmic form the author has chosen. (Anapestic tetrameter is displayed as . . / . . / . . / . . /, for example.) If the writer isn’t sure what that will sound like, a single keystroke will cause the program to “play” the rhythm aloud in a series of bleeps and toots.

[…]

An author can pick all his end rhymes first. As soon as he decides on the first line-ending, the program obligingly generates a long list of rhyming words from which to choose. He selects one, punches a key, and the rhyming word is inserted at the end of the second line and the color-scheme is adjusted accordingly. He then fills in the rest of each line until the poem is completed.

If the electro-bard is worried that his composition does not match the desired metric arrangement, he can strike another key for an instant analysis: The program chews through the poem, compares it against a database of English pronunciation, and re-displays the text with the accented syllables highlighted in a different color from the unaccented. It also counts the beats in the line and displays an “equals” sign if the meter is right, a “+” if there are too many beats, a “-” if too few.

Curt Suplee reports on Michael Newman’s “Poetry Processor”, Washington Post (1987)

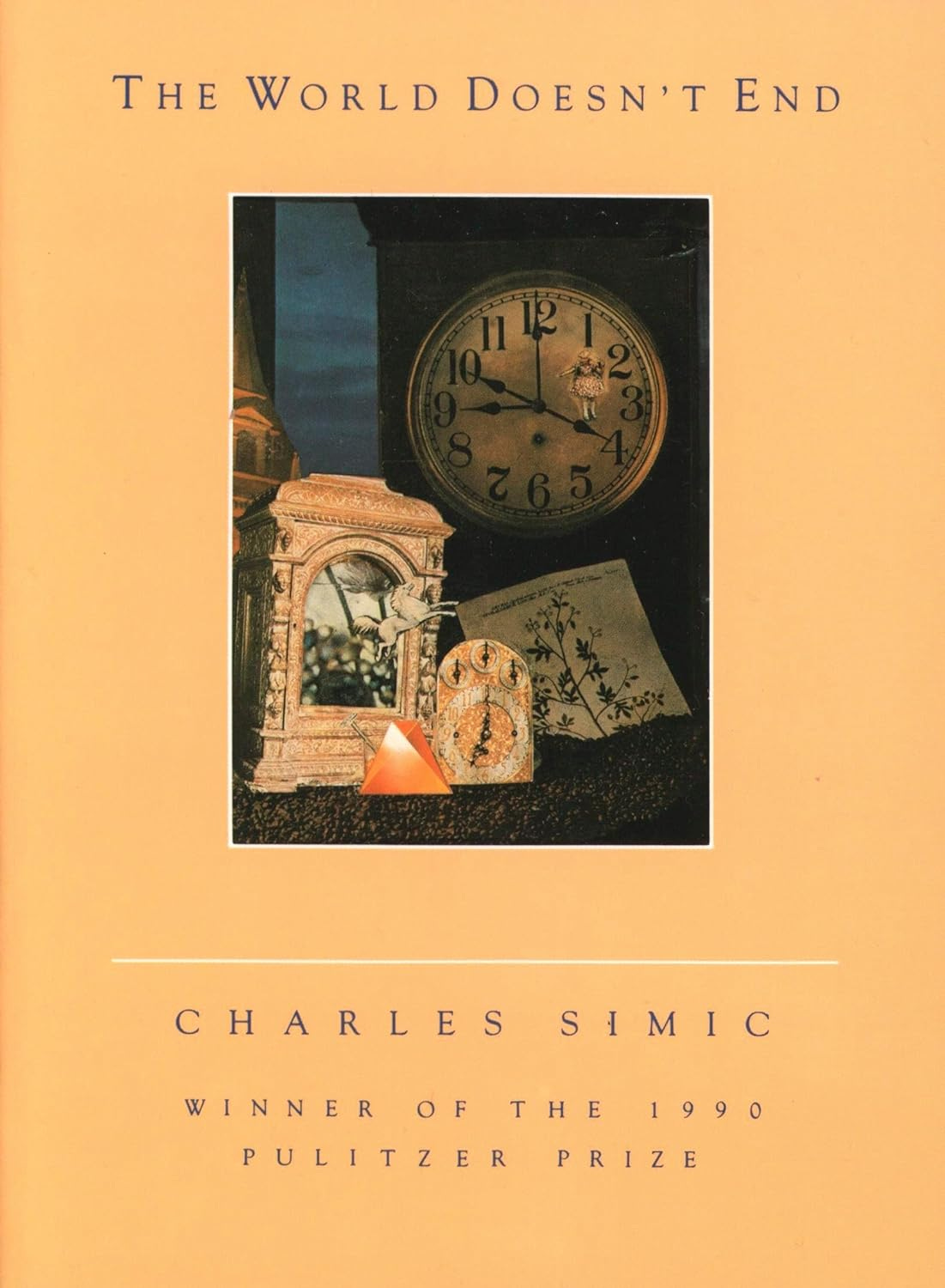

It is my habit to revisit old notebooks from time to time and see if any of the drafts I’ve left behind can be salvaged. I never paid any attention to this other stuff, though, until the summer of 1988 when I inherited a computer from my son and decided to teach myself how to use it, and in the process store my poems on disks. One day, not having anything else to do, and since I suddenly liked how they sounded, I read and copied a few of these short passages of prose. By the time I had gone through a dozen notebooks, I had some one hundred and twenty pieces, most no longer than a few short paragraphs. Nevertheless, I begin to think that I might have a book there.

Charles Simic, describing the process that produced his Pulitzer-Prize-winning collection of prose poems, The World Doesn’t End.

https://plumepoetry.com/essay-on-the-prose-poem-by-charles-simic/

Some editors have already learned to recognize word processor logorrhea — a characteristic wordiness and repetition that comes from editing on-screen […] Similarly, the ease of rearranging paragraphs with a computer can, if overdone, turn intellectual structure into mush. In a vaguely medieval prescription aimed at this pitfall, one critic recently insisted that word processors should be limited to documents less than one thousand words in length.

Michael Rogers, “Computers and Language” (1990)

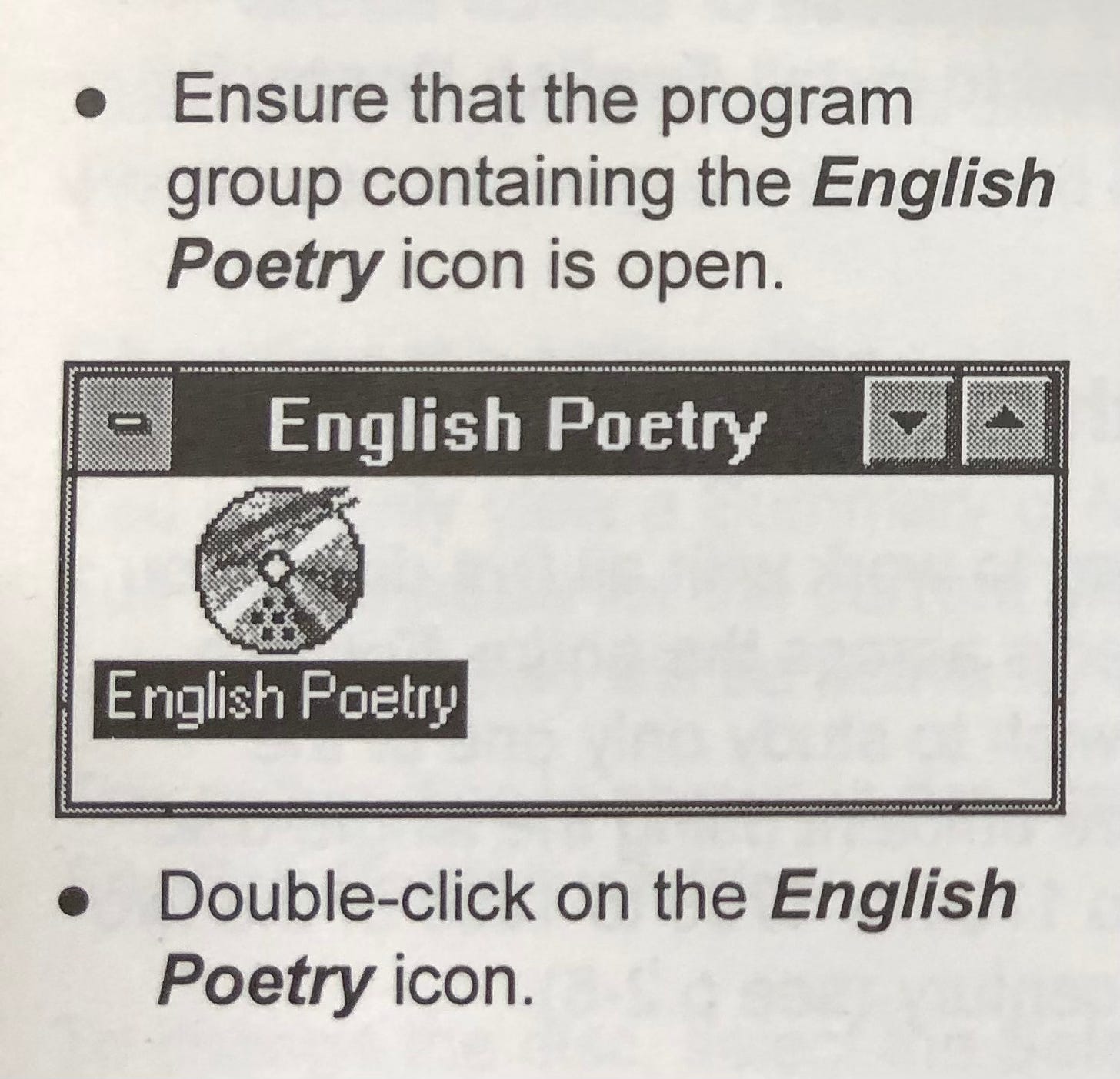

Keyword Searches [Found Poem]

To find “love” anywhere in the database:

love

To find “dream” in stanzaic poems:

dream in <poem> cont <stanza>

To find “God” in all headings and titles:

(god in <head>) or (god in <title> in <source>)

To find “love” anywhere other than in a poem:

love not in <poem>

To find “sonnet” or “sonnets” in division titles:

(sonnet* in <head> in <doc>) not in <poem>

To find “love” or “heart” in all dedications:

love or heart in <dedicat>

To find “moon” in poems that do not contain “night”:

moon and not night in <poem>

The English Poetry Full-Text Database CD-ROM Edition Software Version 4.0 (1995), User Manual: Appendix D

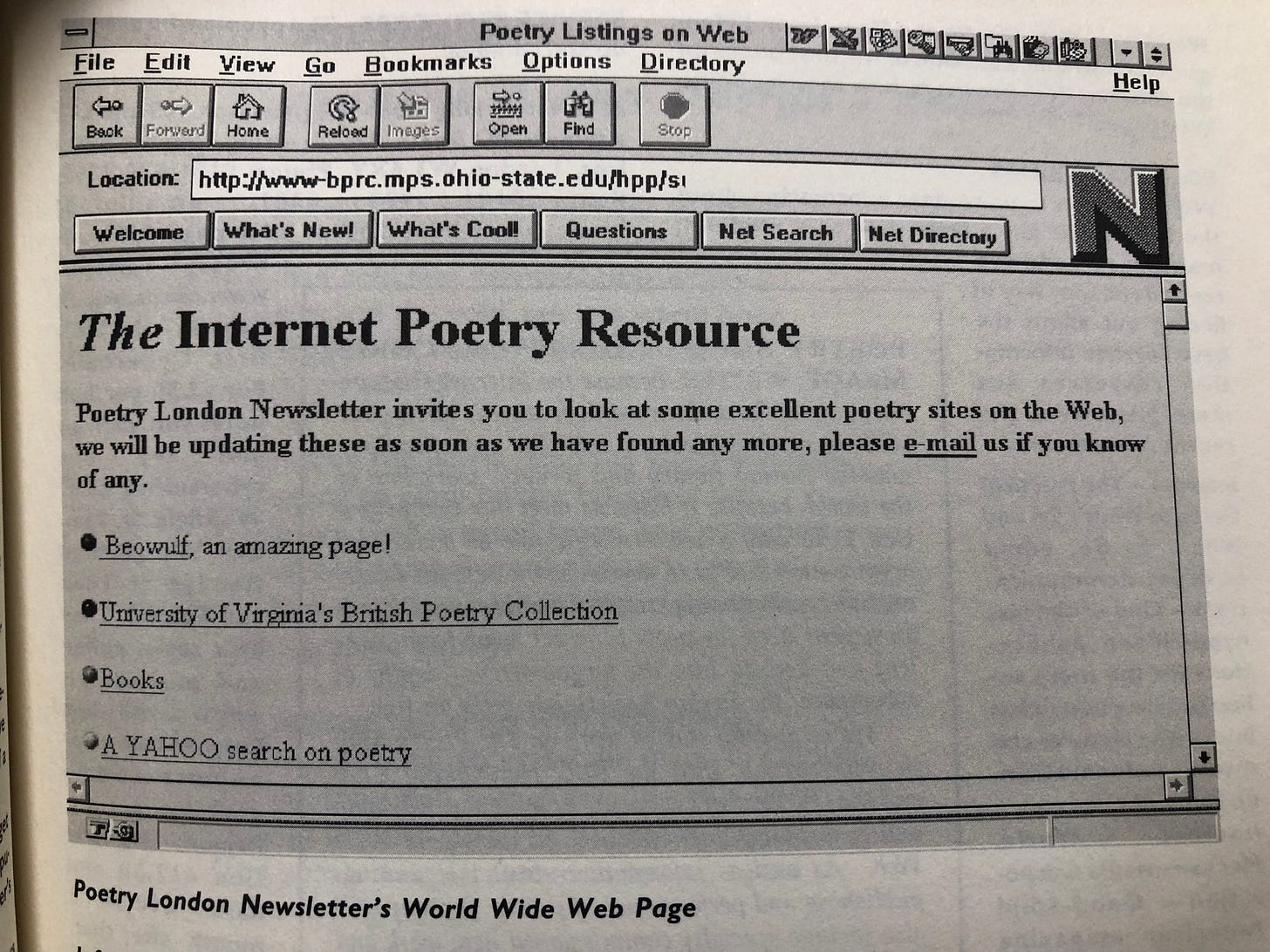

The wild card this year is the Internet: the Poetry Society arrived in cyberspace in February. At the moment, waiting long minutes for graphic files to download must be very like the experience of a former generation listening to early crystal sets: it’s magnificent but also pretty awful.

Peter Forbes, Poetry Review editorial (Spring 1995)

Things on the Internet are happening with such dizzying rapidity that a good part of the information in this chapter could be out of date by the time you read this. By the time we finish writing this sentence, three new poetry sites will have been launched on the Web.

[…]

There are over five hundred — and counting — literary journals currently on the Web.

[…]

So by all means, enjoy what the electronic age has to offer in terms of convenience, ease, and connection; but don’t spend so much time netsurfing that you neglect the true work of a poet — simply to write.

Kim Addonizio and Dorianne Laux, The Poet’s Companion: A Guide to the Pleasures of Writing Poetry (1997)

Please do not submit poems by e-mail

Thumbscrew magazine submission instructions (1998)

NOTES

Almost four decades after the invention of the Poetry Processor — which got a similar flurry of media coverage to poems generated by AI last year — I’m still sceptical that computers are ever going to be any good at writing poetry:

I've never thought about Amstrad + poetry + 90s, but this reminds me that I started a poetry MA in 1994 and arrived in Bristol with a shiny new Amstrad (for essays rather than poems). The graduate centre had dial-up internet and there was much talk of a poetry database currently being created that would allow us magically to search for any English language poem by a single word. I had the impression of teams of scribes uploading poems day and night.

Think I still have a 5” floppy disc somewhere with some early musings. The thrill of printing to a dot matrix. It was almost as if I had published my own pamphlet. We had taken control of the means of production…sort of.