Discover more from Extropic Thoughts

Vernor Vinge, Natasha Vita-More, and David Brin

Vernor Vinge died on March 20, 2024, at the age of 79, in La Jolla, California. He had been suffering from Parkinson’s disease. Vernor wrote excellent stories, popularized the idea of a Technological Singularity, and was a lovely person.

To the best of my knowledge, Vernor did not get cryopreserved. He has no chance to see the future he envisioned so boldly and imaginatively. The near-future world of Rainbows End is very nearly here. (Hal Finney reviewed the book in Extropy Online.) Part of me is upset with myself for not pushing him to make cryonics arrangements. However, he knew about it and made his choice.

Among Vernor’s remarkable books are True Names (developed out of a 1981 novella), which I read in 1987 and again last year. This was probably the first plausible portrayal of cyberspace and a tremendous influence on later writers such as William Gibson and Walter Jon Williams. As David Brin notes, the book was “even more prophetic about the yin-yang tradeoffs of privacy, transparency and accountability.” I greatly enjoyed the libertarian background of “The Ungoverned” and “The Peace War”, which he put together as Across Realtime, my signed copy of which I read in 1993 and again in 2001.

I was fascinated by the long-term perspective in Marooned in Real Time, which I read in May 1989. Perhaps his most famous novel aside from True Names is A Fire Upon the Deep, which I read in February 1993. His use of the “zones of thought” to get around the problem of writing science fiction in the face of the Singularity was clever and resulted in a masterful novel. I recommend the sequels A Deepness in the Sky and Children of the Sky. You should also read his short stories, collected in Threats and Other Promises or, more completely in The Collected Stories of Vernor Vinge.

In multiple books, Vernor created fascinating aliens – very far from the almost-human aliens of Star Trek. His aliens differ not just in form but in mentality and social organization. Two classic examples are the pack-mentality Tines in A Fire Upon the Deep and the intelligent spider-like aliens in A Deepness in the Sky.

Besides his brilliant science fiction, Vernor was a professor of math and computer science at San Diego State University until he retired to write full time.

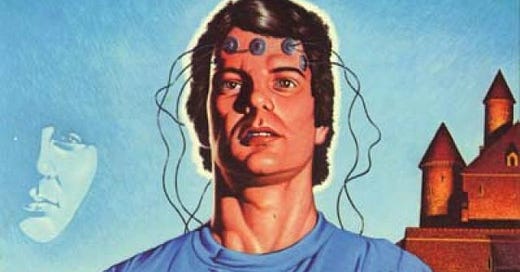

Vernor was the first to publicly explain and popularize the Singularity concept. (Before that, in his second published short story, “Bookworm, Run!” in the March 1966 issue of Analog Science Fiction, he explored the theme of artificially augmented intelligence by connecting the brain directly to computerized data sources.) We reprinted his classic essay, “The Coming Technological Singularity: How to Survive in the Post-Human Era” in The Transhumanist Reader. Although he is the person most closely associated with early use of the concept, he credits mathematician I.J. good who wrote of an “intelligence explosion” in 1965:

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an 'intelligence explosion,' and the intelligence of man would be left far behind... Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control. It is curious that this point is made so seldom outside of science fiction. It is sometimes worthwhile to take science fiction seriously.

The Singularity is really several concepts, more or less closely related. Vernor used the term to refer to a future point where change will be driven so radically by superintelligent machines that we cannot conceive of life after than point.

My use of the word “Singularity” is not meant to imply that some variable blows up to infinity. My use of the term comes from the notion that if physical progress with computation gets good enough, then we will have creatures that are smarter than human. At that point the human race will no longer be at center stage. The world will be driven by those other intelligences. This is a fundamentally different form of technical progress. The change would be essentially unknowable, unknowable in a different way than technology change has been in the past.

An analogy I like to use is Mark Twain and the goldfish. If you have a time machine, you could bring Mark Twain forward into 1997. In a day or two, you could explain everything to him about how the world works (and I think he would love it!). On the other hand, if you were to bring in a gold fish and give the gold fish the same treatment -- try to explain to the goldfish what's going on in 1997 -- the goldfish would remain permanently clueless. That is the difference that I see between current notions of technical progress and the transformation represented by the Singularity. Progress after the Singularity will be fundamentally and qualitatively different than progress than in the past.

My wife, Natasha Vita-More and I met with Vernor in San Diego in 1997 as well as at a conference (on space, if I recall). Natasha interviewed him and published his thoughts in Create/Recreate. This would have been after he wrote A Fire Upon the Deep but before A Deepness in the Sky. When asked if had changed his mind about when the Singularity might occur, he said that his estimates had not changed and “I’d be surprised if it happened before 2004 or after 2030.” He also said, “I do not regard the event as being a certainty; it is simply one of the more plausible scenarios.”

He also considered whether the Singularity can be prevented and what happens to creativity with or without the Singularity.

NVM: Shall we push the Singularity Curve, or attempt to prevent it?

VV: If the Singularity can happen, then I doubt if it can be prevented. There are certain things that may or may not be possible to do with technology. If they can be done, they grant immediate and enormous advantages to the groups that bring those advances about. Trying to prevent the Singularity by laws or public disfavor is essentially futile. If such measures guarantee anything, it is that the law passers and the abstainers will be the losers.

(At the same time, a crash government program to force progress to go faster than what a myriad of independent researchers can do, would probably not be helpful. There have been some spectacular examples of large sums of money being spent trying to force the technological curve, with unsatisfactory results.)

When Natasha asked him about creativity and the arts in the future, Vernor had some interesting thoughts:

VV: Imagining what creativity and aesthetic issues might be for early posthumans is very intriguing. For these creatures, creativity and art might be among the most pleasurable aspects of the new existence. I believe that emotions would still be around, though more complicated and perhaps spread across distributed identities. In writing stories, I have tried to imagine emotions superhumans have that humans don't have. Creativity may be entirely different from before, and this would depend in part on what types of emotions are available.

A more concrete conclusion comes from our own past: before the invention of writing, almost every insight was happening for the first time (at least to the knowledge of the small groups of humans involved). When you are at the beginning, everything is new. In our era, almost everything we do in the arts are done with awareness of what has been done before and before. In the early post-human era, things will be new again because anything that requires greater than human ability has not already been done by Homer or da Vinci or Shakespeare. (Of course, there may be other, higher creatures that have done better, and eventually the first post-human achievements will be far surpassed. Nevertheless, this is one sense in which we may appreciate the excitement of the early post-Singular years.)

But here is a very different possibility: maybe the self-aware part of a superhuman would not be bigger than human. This situation is fairly imaginable. It's an extension of our own situation: the part of us that is self-aware is probably a very small part of everything that is going on inside ourselves. We depend on our non-conscious facilities for many the things. (It's amusing that some of these non-self-aware facilities, such as creativity, are also cited as things that differentiate us from the "nonsentient" world of machines.)

I am already missing Vernor’s writing and his personality. I wish he had been cryopreserved so that there would be some chance that I would enjoy him again. As it is, I say another painful goodbye to a remarkable mind.

Fascinating, and a really nice tribute.