Discover more from ADHD Open Space

What do you do when everything stops working?

When your tools don't cut it, it may mean you need a different kind of resource. Luckily, it's something everyone has some access to.

One of the things that I haven’t seen mentioned a lot in all of the writing about late-diagnosed ADHD is the phenomenon that occurs after you learn to recognize it — and it seems to get worse.

It may just be confirmation bias. As I tell you that I used to drive a dark blue Prius, it’s a pretty sure thing that it will seem like there’s a lot more dark blue Priuses (Prii?) in your neighborhood, on your commute, in the parking lot.

Of course there aren’t any more dark blue Priuses than there were before — you’re simply noticing more dark blue Priuses because at this point I’ve said “dark blue Prius” enough times to prime your brain to be alerted to them.

You might even wonder, when you see one, if perhaps I’m driving it. Spoiler alert: I’m not. I no longer have a dark blue Prius.

But when I feel like I am getting “worse” — wait, let’s not phrase it that way. There’s a poor choice of subject, as well as a “judging” label in there.

Trying again:

When it seems that the expression of my ADHD is getting more intense, more prevalent, more inescapable instead of less — it’s possible that I am simply more aware of the particular ways and when’s that my brain does not quite fit into the world that I live in.

Could be nothing more than that.

Putting labels like “judging” and “confirmation bias” on the feeling does not change the fact that it feels like I am getting worse.

Not only that, the things that I used to compensate for the ADHD years and decades before I knew I was diagnosed — strategies to keep focused, or organized, or motivated — don’t seem to work as well.

Part of that is because now they no longer seem like smart choices and valuable skills. Instead, I recognize them for what they are: desperate hacks. Tricks to find some way of fooling either my brain or the people around me that I, too, am a functioning adult.

If I wanted to be generous, I could use Dr. Barkley’s reference of “scaffolding”.

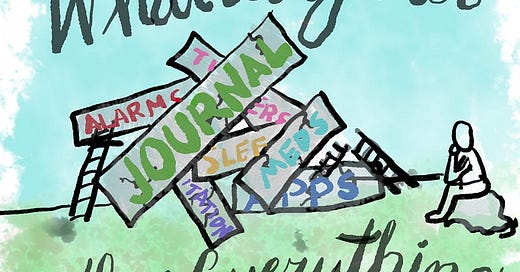

Recently, though, I’ve felt a lot like that drawing I made. I have many, many tools at my disposal. I could easily talk for 30 minutes nonstop about meditation, about movement, productivity, workflows, hell, I could talk for 30 minutes just about timers.

Pray you never get stuck in an elevator with me.

But it doesn’t matter.

Sorry, G.I. Joe: knowing is not even close to half the battle.

With all of these tools at my disposal, in my current phase of life, none of them seem to work as well as they used to — if at all.

The fact that these skills and tools — some of which I’ve invested thousands of dollars and hours of time on — seem to have a shelf-life is horrifying. If I can become as attenuated to a productivity method as an addict can to a drug, why bother?

Nothing is going to work for long. I’ll always have to find some new hack.

And then there’s the fact that I write and talk and create extensively about those very techniques to manage, compensate, and, where possible, thrive with ADHD. I have even started a few private consulting sessions, and they seem to be helping!

It’s not about impostor syndrome any more. It’s a different trope:

the cobblers-child-has-no-shoes situation.

It’s a particular manifestation of the G.I. Joe cognitive fallacy:

Knowing that ADHD often includes heightened versions of

imposter syndrome,

perfectionism,

and a unrealistic set of expectations connected to my self-esteem

does not change the fact that I still feel all those things. It’s just an extra layer of feeling fake, a little more broken — because I feel like I should be able to fix it.

Making my inner dialogue useful.

Luckily, I also have a pretty active self-talk habit — which has basically turned into my own “inner ADHD coach.” The first thing it told me, earlier in the week when I was feeling this way, is also a true thing: “You can’t fix a broken system from inside the broken system.”

It was a paraphrase of something attributed to Einstein, which is pretty powerful.

I realized I was not going to be able to address those feelings of unfocused procrastination and frustration in the middle of the work week, struggling to get even my minimum viable tasks done.

(My inner ADHD coach also pointed out that I had just returned from vacation with a partner who had gotten extremely sick and my own less severe version of “Con crud”, and therefore it was likely that I was going to be less effective at work and experience higher impact from my ADHD while I was sick, because, inconveniently, I am also a human.)

I looked ahead in my week, saw that there was some very open time on the weekend, and made the active choice to not schedule anything. Instead, I spent the time doing some journaling, brainstorming, visual thinking, some rearranging of my environment, and analysis of my weekly and daily routines. I wanted to spend the time using everything I have learned about how my brain works to make sure that the next week started with a plan for making things better.

Sometimes the fixing has to wait.

That’s a useful lesson. Even if we have all of the tools we need to figure things out — and usually we do — the thing we forget is that we also need to create the time and the space to use them.

The bard put it best, through the voice of Hamlet: “if the time be not now, yet it will come — the readiness is all.”

Or maybe it was that other bard, Mark Knopfler: “Sometimes you’re the windshield…sometimes you’re the bug…”

Not sure it’s exactly the same concept…but it’s definitely resonant with my experience of ADHD.

If you’re looking for some organization, workflow, or productivity strategies with or without ADHD, let’s talk!

You can schedule a discovery call by clicking on this button: