Discover more from 5AM StoryTalk

The Untold Horror Story of My First Screenplay Sale

When I sold my first pitch, I celebrated...too soon

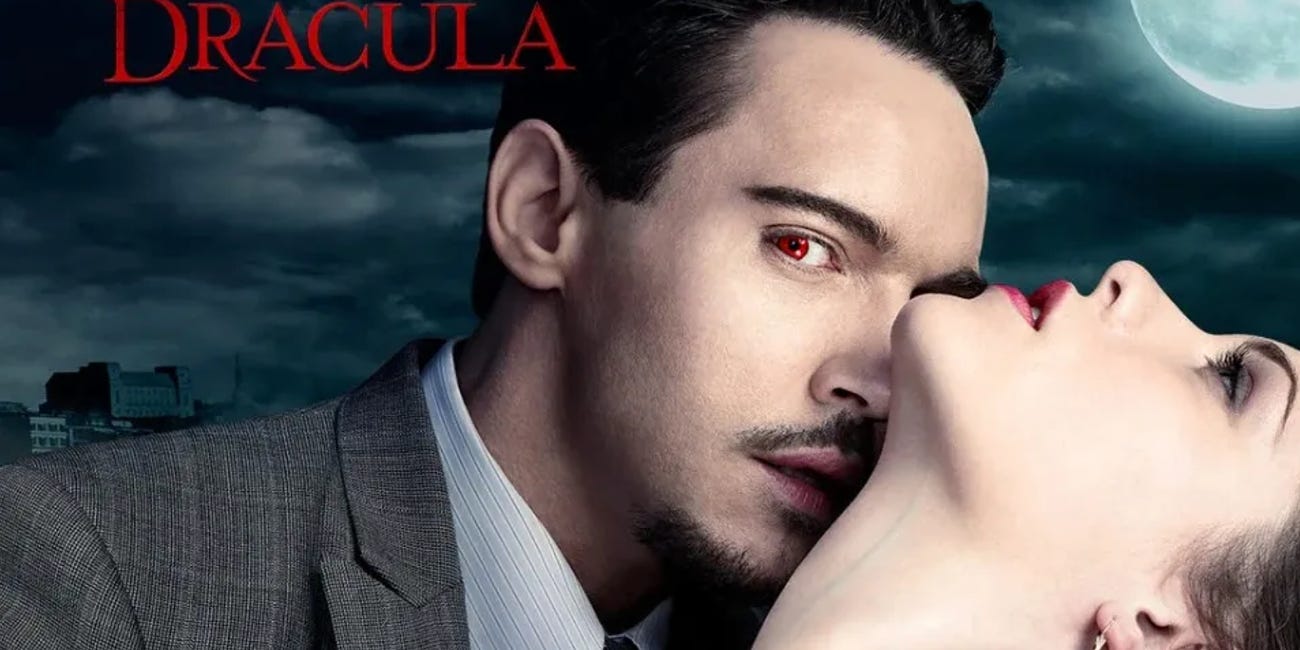

Many of you have read about my horror story creating “Dracula” (2013), something I often call a cautionary tale for screenwriters about what can happen when all your dreams come true. Well, it’s not the only development story from hell in my life. In fact, it’s not even one of five or six – which, let me tell you, is far from unique in Hollywood. What is unique is how often I’ve found myself working with people who, after the fact, everyone around me – sometimes even my reps – said some version of, “Oh god, everybody knows not to work with that person.” Except when you’re new to the business, still emerging as a so-called talent and desperate to secure any work you can, you don’t stop to ask these kinds of questions when someone says they’ll pay you to write anything for them. You take the money and hope for the best. These days, though: I always ask these questions.

I’m going to share with you now the story of my first feature screenplay sale, in the hopes that it prepares you for similar if similar ever comes your way. But also, just because I think it’s an amusing yarn, at least in hindsight. Up until now, I’ve only discussed this in a roundabout way here, so this will fill in a few blanks for some of you.

Just to play with the forms I use at Substack, I’ll present the story to you in the form of a beat sheet. Notes within parentheses will indicate observations from the present about these events. I’ll return at the end for a quick wrap-up.

Int. Hotel Lobby – Day

I pitch a new idea to my MANAGERS. (I’ll come to realize this is the best pitch of my entire career, the perfect one liner when it comes to action films.) Here it is: “The greatest thieves and scoundrels of Arabian Nights assemble in Ocean’s Eleven fashion to pull off the greatest heist of their careers.” And I want to call it Thieves of Bagdad, inspired by my passion for the classic film Thief of Bagdad (1940).

My managers tell me this isn’t a good use of my time since nobody in Hollywood will want to buy another desert film since Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time is due to come out soon. I explain this isn’t a “desert film”, whatever that means anyway. It’s primarily set on the ocean, in colorful cities and lush jungles, and in snowy mountains – just like the classic tales. I also point out that the cast would be wildly diverse. Sinbad and Scheherazade are Subcontinental Asian (Indian/Pakistani/etcetera) so we could get the biggest stars of Bollywood, Aladdin is Chinese which would mean Chow Yun-fat (a dream come true for me), and so on.

Nope, doesn’t matter, don’t pitch it, I’m told. This is how reductive Hollywood can often be: “Only one desert movie at a time” — again, whatever that means. I’ll let you draw your own conclusions.

Int. Development Exec’s Office – Production Company – Later That Day

Two hours after my in-person meeting with my managers, I pitch Thieves of Bagdad to a YOUNG DEVELOPMENT EXECUTIVE (YDE). They immediately walk me into their boss’s office and ask me to repeat the pitch. THE PRODUCER tells me he fucking loves it. Can we pitch it together? Hell yes, I say.

But there’s one problem: we need a white character.

Int. Home Office – My Apartment – The Next Day

I pitch my solution to the Producer’s challenge of “how do we get a white character into an Arabian Nights project?” I’m determined not to just white-face the cast.

“So, you know the revisionist take on Robin Hood, right? He was a Crusader before he was a Prince of Thieves. So, one of our cast of super-thieves will be a young Will Scarlett, one of Robin Hood’s future Merry Men. Bagdad is a wildly diverse city at this time, so this kid is an escaped slave, living on the streets, sort of a Parkour master. He ends up joining Sinbad and Ali Baba on their quest. Sinbad would be Danny Ocean, Ali Baba would be Rusty Ryan, and Will Scarlett would be Linus Caldwell. At the end of the film, we’ll do a post-credits scene where Will, captured in Jerusalem, is thrown in a prison cell with…Robin Hood.”

I add, “Our sequel could be the Thieves of Bagdad versus the Thieves of England.” The Producer says he fucking loves it. We can get Zac Efron.

(Truth is, I loved the idea, too. I still like the idea of people of color constantly berating and othering this obnoxious token white kid rather than a POC being tokenized in this kind of story.)

Int. Studio Exec’s Office – Big Studio – A Few Days Later

I pitch Thief of Bagdad to a STUDIO EXECUTIVE, exactly as I had to the Producer. I repeat the detail, “It’s Pirates of the Caribbean meets Ocean’s Eleven.”

The Studio Exec buys it in the room. Their parting command: “Write me that – Pirates meets Ocean’s – and we’ll make this.”

Int. Hallway – Big Studio – Moments Later

While walking to the elevator, the Producer and his boss, a LEGENDARY PRODUCER, congratulate me, then tell me to ignore the Studio Exec. “Those movies are terrible,” I’m told about one of the biggest franchises of the 21st century and one of the greatest heist films of all time.

Int. Legendary Producer’s Office – Producer’s Office – The Next Day

I’m sitting down with the Legendary Producer, Producer, and YDE. The Legendary Producer is telling me how much they loved Thief of Bagdad as a little kid. In particular, they loved the monkey in it. Can I put a funny monkey in my script? “Yeah, absolutely, I love that idea,” I lie.

Int. My Home Office – My Apartment – Later That Day

I’m speaking to my accountant, who is about to form my S-Corp to accept payment from the Big Studio for my services. He’s been after me for a name for the company for a week now. “I’ve got it,” I tell him. “Dancing Monkey Productions.” (I was the monkey, if that wasn’t clear.)

Ext. Patio - The Crescent - That Night

More than thirty friends — including my team of managers, agents, lawyers, and business manager (really, this was absurd to type) — show up at this Beverly Hills bar to party with me on its street-facing patio. They know how hard I’ve worked to make it this far. I’m a professional screenwriter, woo-hoo. Soon to be a member of the Writers Guild of America West. I still can’t believe it. Dreams really do come true!

Int. My Home Office – My Apartment – The Following Week

I’m on the phone with my managers. As my voice trembles, I inform them that after much consideration, I am ending our relationship. Had I followed their instincts, I would still be unemployed and who knows how long, otherwise, it would’ve taken to finally break into the industry? This led to a valuable realization for me: All you really have are your creative instincts. (You can read more about this here.)

Int. Meeting Room – Producer’s Office – Two Months Later

I have delivered my first draft and been privately told by the YDE that they are very happy with it. I’m now sitting across from the Producer and YDE in a dark meeting room. The Producer has a printout of the script for me; they’ve also printed out a copy for me that I didn’t ask for, as I have my laptop with me, so I’ve privately groaned about the tree that died for a 120-page manuscript I’m going to recycle as soon as I get home.

“Sony has a Sinbad project,” the Producer tells me. “They’ve hired writer after writer – huge names – to work on it. They’re, like, $6 million in at this point. This script you wrote is better than anything they’ve been given.” (Looking back, I remember how mind-boggling it was to be told this; I’d been paid $90K for my script, so I seemed like both a deal and the next big thing if I was really this good.) “We have a few notes,” the Producer goes on, “but nothing big.”

The rest of the meeting is relatively mundane. I’m given mostly smart observations by the YDE, but the Producer is fixated on character. They think Sinbad needs work. I try to interrogate this, so I can go home and answer the note as strongly as possible.

“Look at Indiana Jones,” I’m told. “What do we know about him? He has a hat, a whip, he’s afraid of snakes.”

(In hindsight, what I said next was the exact opposite of what I should’ve said. I didn’t know better. I thought I was discussing my work with a peer who wanted the best script possible rather than someone who needed to have their ego fluffed.) “But details like that don’t give a character character,” I reply. “They make them caricatures without all the other stuff, the goals and how they set about achieving them — their decisions and why they make them — that’s what really matters”

The Producer doesn’t find this amusing, but reiterates how good the script is. I’m asked when I can get the changes to them. “A week or so,” I say, “maybe sooner.”

Int. My Home Office – My Apartment – Six Months Later

In the film, we would jump cut forward in time. I’m on the phone with my agents. “Twenty-six drafts, and they still won’t let me deliver it to the studio! I’m done. I can’t do this anymore.”

I’ve completed twenty-five more drafts since I delivered the first one to the Producer. Several of these were page one rewrites, starting completely over on a script that I had previously been told was amazing. I’m still being asked to do more. When I’ve queried other screenwriters if this has ever happened to them, they all concede free rewrites are part of the game, but that’s usually in the range of three to, in the worst case scenario, ten. Twenty-six drafts and still not being allowed to deliver it to the studio, so I can get paid, is extraordinary. Concerned that I was the problem, I’d also sent my most recent draft to my agents (who loved my first draft). They loved it. I sent it to other screenwriters. They thought it was solid; I’d done my job.

“Twenty-six goddamn drafts!” I keep repeating to anyone who will listen, trying to understand what’s happening to me.

Stepping away from my “beat sheet” for a moment: the following is an anecdote about the Producer I was working with. They helped develop an early version of the Planet of the Apes reboot that Tim Burton would eventually direct. The words here are not mine; they were taken from elsewhere and modified for clarity.

Fox became frustrated by the distance between their approach and screenwriter Terry Hayes' interpretation of Oliver Stone's ideas. As producer Don Murphy put it, "Terry wrote a Terminator and Fox wanted The Flintstones". Fox studio executive [My Producer] felt the script could be improved by comedy. "What if Robinson finds himself in Ape land and the Apes are trying to play baseball? But they're missing one element, like the pitcher or something,” My Producer continued. "Robinson knows what they're missing and he shows them, and they all start playing." My Producer refused to give up his baseball scene, and when Hayes turned in the next script, sans baseball, My Producer fired him. Dissatisfied with Sellers' decision to fire Hayes, the project’s direct Phillip Noyce left Return of the Apes to work on The Saint.”

Int. Meeting Room – Big Studio – A Few Days Later

I meet with the Studio Exec, Producer, and YDE. The Producer spends much of the meeting telling the Studio Exec they’re wrong about the draft I demanded be turned in. It’s clear now I am completely and utterly fucked.

Int. My Home Office – My Apartment – A Few Days Later

I’m on the phone with the Studio Exec, who tells me I am indeed completely and utterly fucked, though maybe not in those words. Someone has to be blamed at the Studio for this clusterfuck. It’s not going to be the Legendary Producer’s company; that’s politically impossible. So, I will be blamed instead.

I’m advised to write the best official second draft I can, “swing for the fences,” because it will be a writing sample now to hopefully get more work in the future.

Int. Restaurant – Five Years Later

I’m having dinner with my friend, a producer, a few years after development of Thieves of Bagdad was abandoned by the studio. Thieves of Bagdad was rewritten by a screenwriter who would go on to become a close friend, by which point it was renamed Arabian Knights because, I can only imagine, Arabian was less offensive to Western ears than Bagdad. A story about thieves became a story about…knights? Okay, sure. (Despite all this, I wish it had been made. It would’ve meant I’d have a thriving feature career today rather than primarily being a TV writer, which is what I moved into as the feature market dried up.)

My friend, the one I’m dining with, tells me they just had a meeting at the Studio and brought my name up. For the first time in half a decade, it didn’t get him shut down. I don’t understand what he means. He then explains to me what he always thought I knew but I suspect my agents didn’t share with me “to protect me”. “Nobody on the lot could ever get you hired because the studio wanted nothing to do with you,” my friend says. “What I was always told was that you shit the bed on Thieves of Bagdad.”

In other words, I was shunned by a studio for years because of how catastrophic the development process, led by the Producer, was for all involved.

It’s reasonable to wonder, as I did when all this was happening, if I was somehow to blame. Was my writing just that bad?

I have no way to counter that argument except to say that my agents didn’t think so, my peers didn’t think so, the person who was eventually hired to rewrite me didn’t think so, and the people who subsequently hired me based on the merits of my draft of the Thieves of Bagdad script didn’t think so. My next job landed me on the Black List, which really launched my career. The next one was so well-received the studio bought two more projects from. And then the next, a TV pilot, was greenlit to series. I’ll never understand how all that was the result of me “shitting the bed,” but I guess that’s Hollywood for you.

What really galls me about this whole experience is both the creative trauma it inflicted on me and how one unfortunate collaboration could have such a spectacularly deleterious effect on my career and reputation. I was young and inexperienced as a professional, and these events forced me to question my instincts and how to pursue my career. Had I not been gifted determination and confidence by non-existent gods, I might have been broken by it and abandoned my dream altogether. Don’t let that happen to you, my friends, no matter how bad it gets.

If this article added anything to your life but you’re not up for a paid subscription, consider buying me a “coffee” so I can keep as much of this newsletter free as possible for the dreamers who couldn’t afford it otherwise.

If you enjoyed this particular article, these other three might also prove of interest to you:

Dancing Monkey Productions…LOVE IT!!!!!!

So freaking helpful and generous of you to share. Thank you!