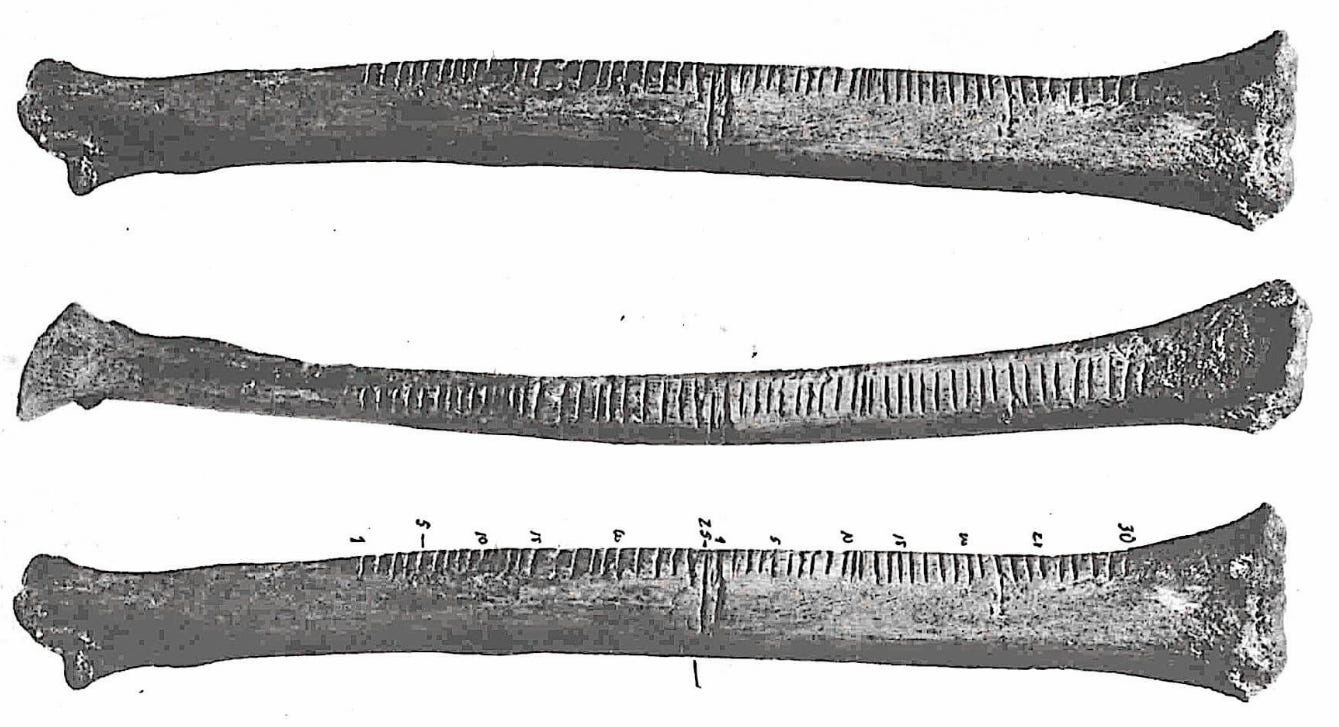

Hachures

Old topographical maps use lines called hachures to indicate slopes and relief. The marks are scored according to steepness, tiny scratches like tallies across the page. When a slope is very sharp, the lines are placed closer together for darker shading. Johann Lehmann, a German botanist who blended interests in physics, natural sciences, and cartography, was the first to use hachures and establish a mathematical methodology for applying them in 1799.

Later models used color-coded lines, green for lowlands and brown for highlands. Despite its logic, there is an intuitiveness to hachures, a deeper artistry from hand to page, a sense of the landscape as it is experienced by the cartographer. An excellent mapmaker can apply hachures in a way that gives the map a sense of a living landscape, as though one could walk out on the page and experience firsthand the valleys and peaks.

Every map is merely an estimate of a space, a momentary snapshot of an eternally shifting scene. Heraclitus said you can’t step in the same river twice. Zeno’s Paradox taught us that you can’t step in the same river once. Existence is change. Hachures, too inaccurate and permanent to represent the ever-evolving slope of terrain, were eventually replaced by contour lines and tints indicating elevation. Perhaps this is why I like hachures so much. They represent the mistakes of human perception and perspective, the land as the cartographer believed it was, the land within the context of experience, red handprints on the wall of cave.

I have lived for thirty-seven years in a land marked by infinite space and time. To inhabit the Saint Francois Mountains is to be surrounded by hachures, descansos, sign posts of the past, reminders of a circular future. It’s a cursed town, true, ever-jockeying for tragedy. Each day on my way to work I pass highway markers memorializing my former students.

When a major gas station chain started construction by the highway outside of town, the city’s leaders reasoned, We have five places to get a pizza. Can’t you put in anything else?

The station’s reply—This is what our customers like—another reminder that, even this, is not for them.

It’s an old story of the colonizers and enslavers who tapped these rocks, then and now, and the curse is in our blood tests. A lawyer recently sent to placate community members angered by a devastating fire at a new battery plant within one mile of three of the town’s four schools—a man emboldened by wealth and the easy target of a town carrying a heritage of mining and mineral exploitation—incorrectly and patronizingly characterized the town by an exaggerated and singular visual: missing persons’ posters. The company hopes to rebuild even bigger than before, assuring citizens that these jobs will revitalize the community: they should be grateful. But the citizens saw something familiar in the smoke.

It is, after all, a town with lead in the soil, unable to grapple with its own past, frozen like dead fish in the water—a town of a million tragedies, miracles, too. I’ve been baptized in these springs more than once. Tuck Everlasting is as real as fried chicken. Joseph Smith came to Missouri looking for Eden, but didn’t find us. Somehow, even the cartographers forgot to look here. As always, only capitalists have an eye for heaven. Hachures all over these hills.

Hachures have always been instructive, good reminders. We figured that out early on. But nature knew long before us. We are, after all, in the grand scheme of things, barely born.

Once, while spotting my husband who was climbing a tree to put up a deer stand, hachures emerged in an unexpected place. I pulled a chair from the back of his truck, set it up under a grove of young pine trees, and began sketching some pale lichen on a stump. I snapped a small twig off a pine nearby that was poking me.

Sitting back to take in a different view, I noticed that each tree had a ladder of dead limbs, sacrifices for each new stage of growth, hachures marking both space and time. As the pine grew and new limbs sprouted at the top to eat up sunlight, old limbs died. A tree, like all beings, is more than a single organism. It is an ecosystem, even in its own cells. It knows better than most of us, though, that care for others is care for the self.

The thing about hachures is that they require the cartographer to consider the entire landscape. Each mark must correlate to the terrain, and accuracy ensures that the shape of the hills rise from the paper.

When I was a kid, I loved stretching out under pine trees, even fake Christmas ones, and looking up through the limbs. I learned this habit from my older sister. Both stars and twinkly Christmas lights look the same when you take off your glasses. My dad built a house in the woods by a dilapidated A-frame cabin. The previous owners–city people, we were told–planted white pines in lines around the property leading back to the cabin in case one of their guests became lost on the ten acres of land. Their pale green was stark in the winter against the dark, bare oaks.

The small pond that we skated across was framed by pines. My sister and those trees are intertwined in my mind. She is the magpie. I’m the heron. But I’m saving those archetypes for another time.

These are the hachures, the marks and archetypes that I can’t seem to escape: the starling, eclipse, fire, boar, rope bridge and more. You’ll see what I mean, the circular nature of this brain and time as I document each one. This won’t be our last look at hachures. I’ve spent my life running from symbolism while crashing into ghosts. But as we are here now, the irrevocable and terrible here, let’s see what they have to say.

Tonight I will draw the pine tree, and I’ll squint at the Christmas lights in these branches. I will pay as much attention to the dead undergrowth as I do the imposing crown, many iterations of body and time. I will feel the context of this being’s experience and see my own reflected in it. The tree is a map, the lines–albeit intentional–will reveal the evolving nature of the landscape of living. I’ll step onto the page. I may get lost.

Strange, these palms against this cave wall. The first lines are clear and isolated, deep incantations against smooth rock; the next extended like fractals, synapses, tree limbs; the last like the skin of a lizard, too little water, too much sun; someone else’s hands, stretched and open, as if letting go–life as I thought it was; imperfect hachures in a perfect hue.

Cicada ornament for a 2024 Archetypal Christmas Tree