I’m going to do a Substack live video interview with Representative Ritchie Torres (D-NY) today at 1PM eastern time. You need the Substack mobile app to watch, but if you’re free I hope you’ll tune in. If you’re not free, I will post the video and audio to the site later. We’re going to talk about his political trajectory over the past few years and the way forward for Democrats writ large.

My New Year’s resolution for 2025 is to try to arrest the internet’s tendency to melt my brain by setting aside time every day to read classic works of literature.

The fiction aspect of this is, I think, important. One reason I’m good at my job is that I’m really good at skimming non-fiction documents, but that means reading non-fiction books (even ones that I enjoy) doesn’t really generate the right kind of mental unplugging. And reading the classics seems like a good project, since old books tend to have complicated sentence structures that require you to actually pay attention.

The first one I tackled was “Middlemarch,” by George Eliot, in part because I thought it would be a nice break from my workday political considerations.

So imagine my surprise when it turns out that one of the book’s plot lines involves the construction of a railroad line and the various NIMBY elements upset about it.

Some context, for those of you who also skipped English literature in college: Eliot is writing in 1871 and 1872, but the book is set in 1829-1832. Middlemarch is a fictional location that’s intended to portray a generic town in the Midlands region (which is just literally the middle of the country), and while the plot primarily concerns a number of mostly ill-fated romances, the theme is the emergence of modern industrial Britain. The railroad plot, though it takes up very few pages in the book, is symbolically important, because railroad construction would have been one of the most obvious ways that Britain changed between the era in which the book is set and the era in which it was published.

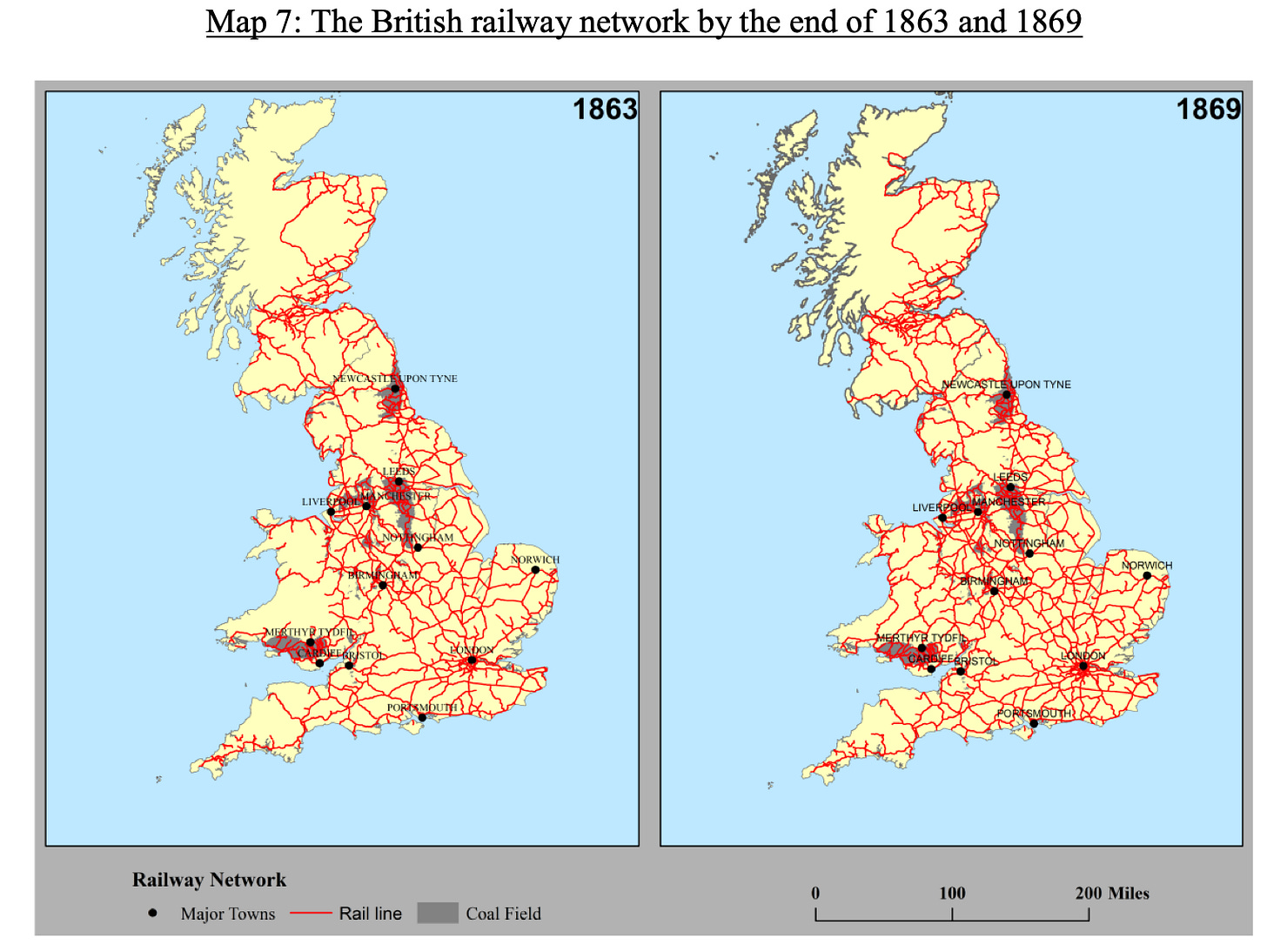

In 1830, there was exactly one intercity railroad in the world: the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, which connected the textile factories of Manchester to the port town of Liverpool. This meant American cotton could move from the docks to the factories more quickly, and finished apparel could move from the factories back to the docks. Forty years later, Britain had an extensive rail network, and the Midlands in particular were criss-crossed by trains linking the countryside to London in the South, Manchester/Liverpool in the North, and the regional hub in Birmingham.

That’s a lot of construction over the course of a generation, and it radically altered the visual landscape of the country. It also, of course, changed the practicalities of life. Before the railroad, London was 15 hours from Birmingham by stagecoach and 20 hours from Liverpool. With trains, the city was three hours from Birmingham and five from Liverpool.

But how did they build so much so quickly? That’s where we turn to Eliot.

You can’t stop progress

One of the many difficulties of railroad construction, now or in the 1830s, is that unless you want to build expensive viaducts, you need to take swathes of rural land that are not actually being served by railroad stations.

Many of the big landowners in Middlemarch, including Sir James Chettam and the Featherstone family, are not enthusiastic about this idea. It’s going to cut up their parish, it’s going to be loud and unsightly, and it serves primarily to benefit new industrial and mercantile interests. Even if the railroad is not per se bad for their economic interests, it is not necessary to advance them. They earn (or “earn”) a living leasing land to tenant farmers, and they constitute the traditional social and political elite of the town and the country writ large. Making it easier to move raw materials and goods to and from various port towns is only going to accelerate the rise of a new class of people who can displace them.

But there are also plenty of downscale railroad skeptics.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Slow Boring to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.