Transform Your Thinking with a Commonplace Book

Capture, Organize, and Revisit the Ideas That Matter Most to You

I’m fascinated by perfect-looking notebooks. I’m not referring to ones with colorful, aesthetic covers or those filled with helpful templates. I love notebooks filled with organized content and valuable insights — genuine relics that are invaluable for the material they contain.

Two that I’ve seen on television shows immediately come to mind.

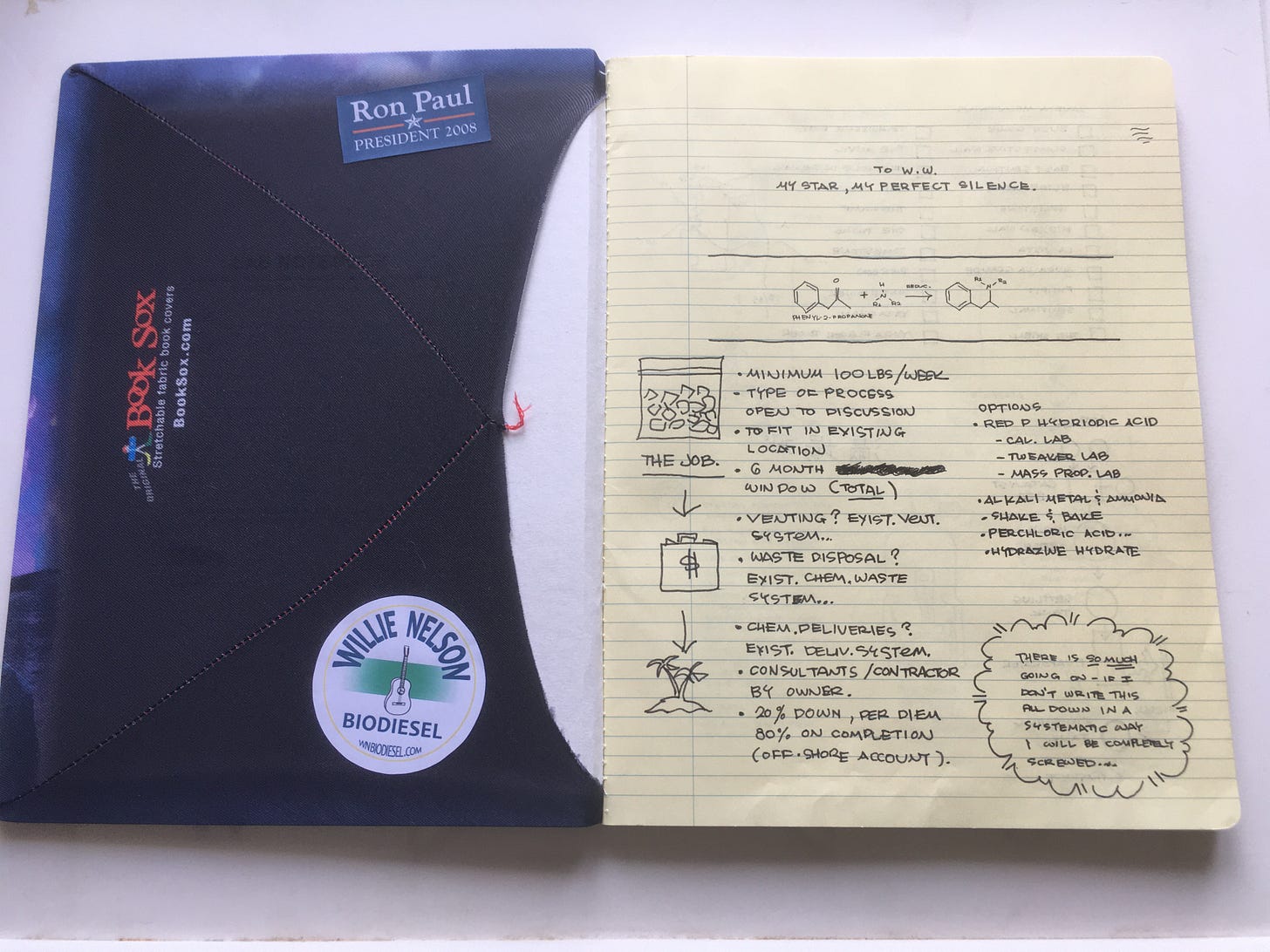

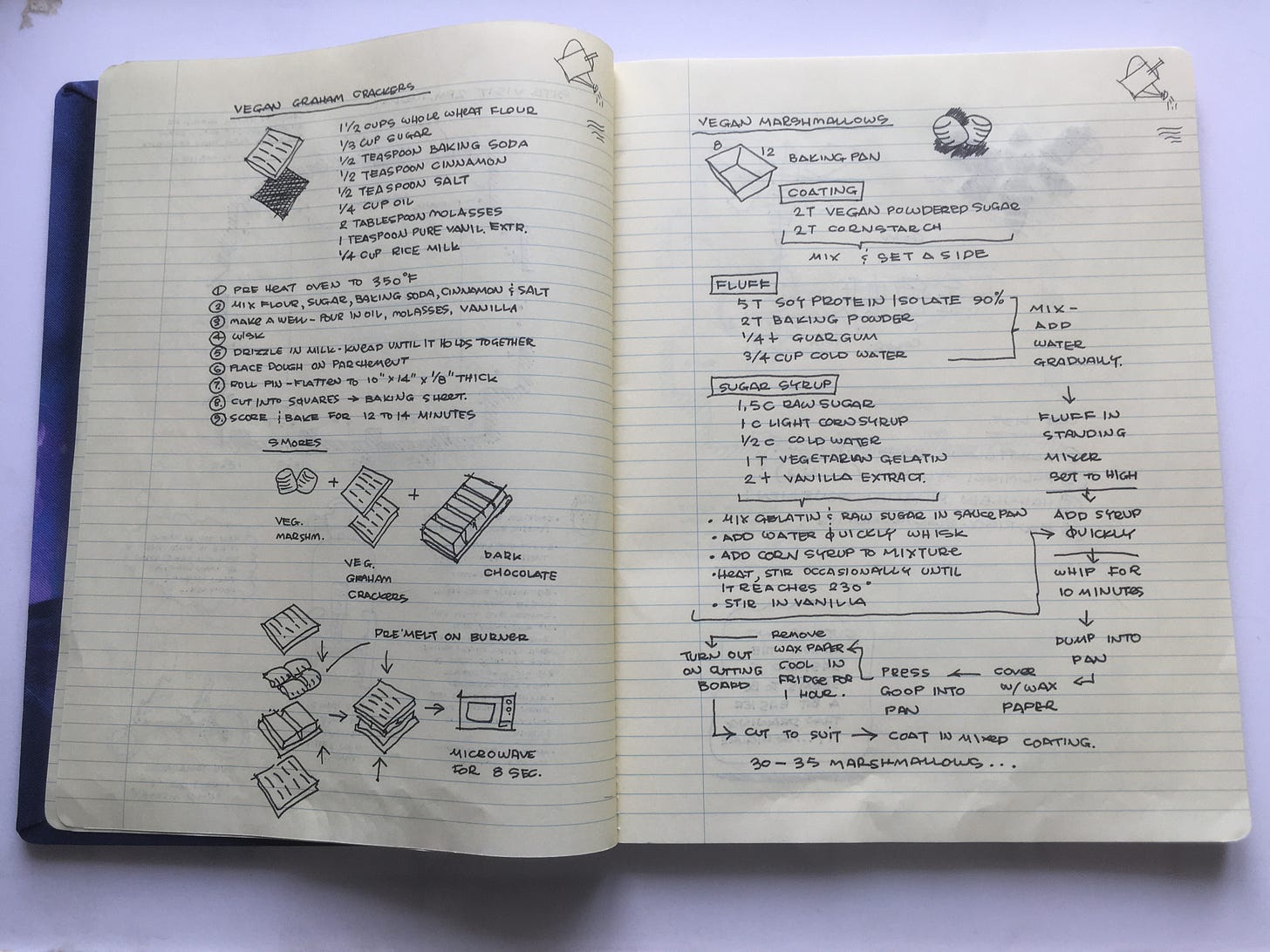

The first is Gale Boetticher’s lab notebook from Breaking Bad, which contains various contents, from instructions for synthesizing methamphetamine at scale to a recipe for vegan s’mores.

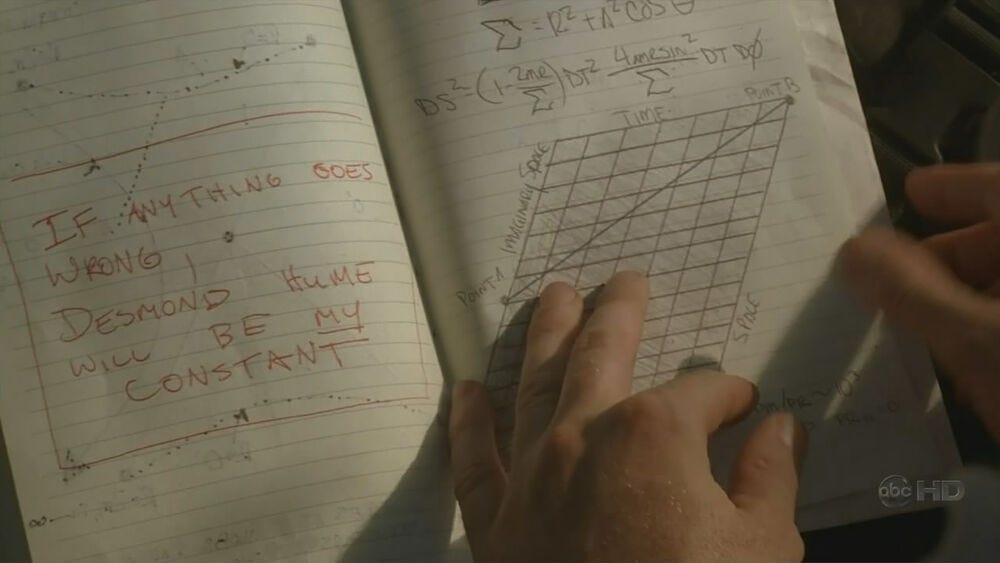

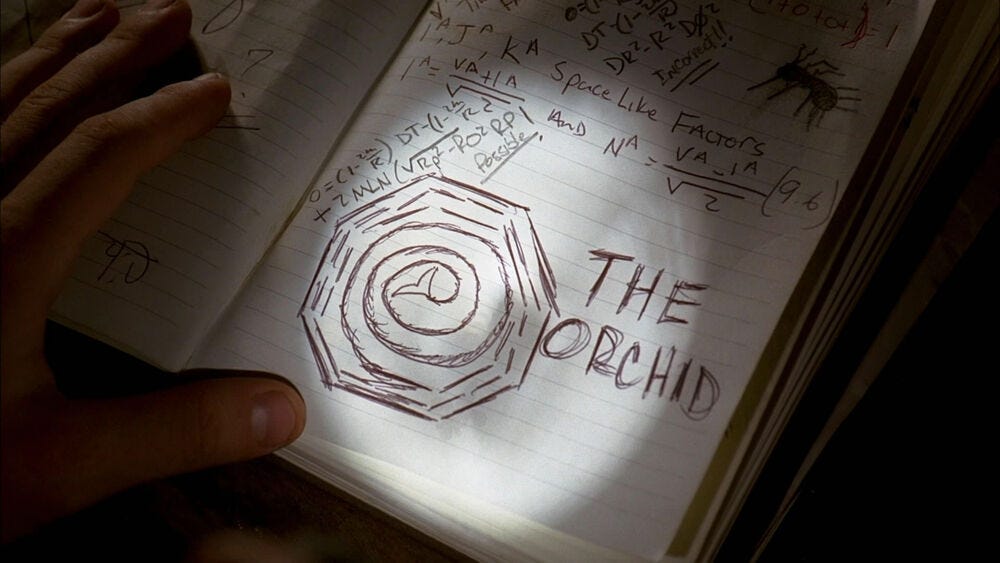

The other was Daniel Faraday’s notebook from Lost, filled with research about space-time and the Dharma Initiative.

I’ve always been envious of people whose notebooks are filled with rich content and look this well-organized. Mine always seem to turn into a jumbled mess. A glance at my notebooks reveals bullets of unfinished sentences, circled or crossed-out words, messy flowcharts, unfinished drawings, half-baked ideas written in margins, and entire pages that don’t seem to fit in.

My lack of order always unsettled me. I’m a planner and like things organized. The idea that others had cracked the code of taking well-structured notes bothered me because I never seemed to figure out a sound system that worked for me.

But more recently, I began to ask myself some questions: What if these examples of organized notebooks didn’t represent all of the author’s notes but were instead a final product generated from earlier drafts? What if these authors had other, messier notebooks containing the raw material that ultimately made their way into this finished product?

The idea seemed interesting. Much like how social media only reflects the life someone chooses to display, it’s logical that a notebook specifically curated for public viewing would be the result of significant time and effort. So, I began to research note-taking systems. Little did I know I was stumbling toward a centuries-old practice called the commonplace book.

I’ve spent the past few months delving into commonplace books. I read about their origins, learned various organizing techniques, and even started keeping one myself. In the rest of this post, I’ll share what I’ve learned and argue why you should consider starting one of your own.

What is a commonplace book?

A commonplace book is a central hub for ideas, concepts, quotes, anecdotes, observations, and more. These valuable pieces of information remain accessible and ready for future revisiting for personal projects, professional work, or other ventures.

Commonplace books are distinct from diaries or journals. A diary or journal, while also a valuable resource, is something you can use to record your thoughts. A commonplace book is like a database for the most useful wisdom you learn. It’s meant to house the knowledge you want to retain throughout your life.

The commonplace book has been around in some form for as long as people have been writing:

The ancient Greeks gave us the word commonplace and were known to capture notes for self-improvement.

Like many traditions that started with the Greeks, it continued in Roman times. Individuals used scrolls to capture Roman legends and abstracts of speeches.

As early as the 7th century, the Chinese kept collections of writings that contained anecdotes, quotations, random musings, philological speculations, literary criticism, and short fictional stories.

In the early 1000s, the Japanese had similar repositories called pillow books, which were collections of notes collated to represent a period in someone’s life.

However, the form of the commonplace book we know today grew in popularity during the late Renaissance and came into its own during the European Enlightenment in the late 1600s.

The printing press was invented around 1440. This technological leap made producing written text more efficient, exponentially increasing literacy beyond the narrow realm of scholars. With the growing number of readers and the expanding volume of material per reader, they soon faced challenges retaining so much information (sound familiar?). The commonplace book was developed to capture sources and inspirations, jot down thoughts, and work out various ideas.

English philosopher John Locke codified this process in 1685 when he developed a methodology for creating commonplace books. His work was republished posthumously in 1706 under the title, A New Method of Making Commonplace Books. Locke developed techniques for entering proverbs, quotations, and ideas. He also provided specific advice on arranging material by subject and category, using key topics such as love, politics, or religion.

Commonplace books come up repeatedly amongst some of the greatest thinkers in history. Here are a few examples of famous people who maintained this practice:

Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations was essentially a commonplace book. Though he didn’t refer to it as one, the work is filled with aphorisms, reminders to himself, and ideas from things he had read.

Leonardo DaVinci kept notebooks that can be considered commonplace books. These notebooks contained sketches, observations, and ideas on various subjects, including anatomy, engineering, and philosophy — an inspiration for today’s multifaceted creative pursuits.

Thomas Jefferson kept several commonplace books for literary and legal matters. In them, he kept track of quotes and passages from books he’d read that he wanted to remember.

While at Harvard, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau were taught about keeping a commonplace book. They shared one devoted solely to poetry.

Benjamin Franklin kept a commonplace book with a wide range of contents. It included historical events, original poetry and epitaphs, a list of street names in Boston, instructions for making dyes of various colors, and instructions for removing spots from different fabrics, among other things.

The practice has remained a proven method for capturing knowledge and fueling creativity to this day. Two of my favorite modern thinkers, Ryan Holiday and Tiago Forte, have written about the concept. They keep a commonplace book to help inspire them throughout their writing, speaking, and creative careers.

Why keep a commonplace book?

People keep a commonplace book for all sorts of reasons, and though each person’s motives may differ, staying consistent with this habit can offer many benefits.

To summarize your thoughts

Have you ever realized, after closing a book, that its key points seemed to vanish as quickly as you read them? Rest assured, this isn’t a sign of poor memory but rather a common challenge in synthesizing information. This is where a commonplace practice can help. People learn most effectively when they distill the essence of what they have read. By rewriting the core ideas we consume in our own words, we can better detail what we genuinely think about a subject. A commonplace book is the perfect place to store these thoughts.

To retain information

We are bombarded with information every day. Scientists have found that the average human consumes ~74 gigabytes of data daily (the equivalent of watching 16 movies) — a number that’s continuing to increase. From all we consume on television, social media, webpages, books, and anywhere else, retaining what you consume is challenging. Writing down the passages you liked, quotes that stuck out, and ideas that inspired you gives you a chance to fully engage with your material. Doing this can enhance your ability to remember that information and turn it into knowledge.

To draw on your knowledge in later works

John Locke once said: “It would be of little purpose to spend our time reading books if we could not apply what we read to our use.” What is the point of learning new things if you can’t apply what you’ve learned to other things in life? A commonplace book helps you store your ideas in a place that can be accessed later in life. By capturing important insights and organizing them for easy reference, you can draw on past lessons and incorporate them into new projects. It turns knowledge into a living resource, ensuring that the ideas you gather through reading and experience can actively shape your future endeavors.

To draw connections across topics

Creativity comes from the connections of ideas across seemingly unrelated things. These links happen all the time in life. In a commencement speech at Stanford in 2005, Steve Jobs credited a calligraphy course as having been essential to the success of the first Macintosh computer. Combining your unique interests into one repository helps you to bring seemingly disparate ideas together. It’s a way to make something personalized to your experiences and interests. Who knows what contribution you could make to society by combining your knowledge into one melting pot and seeing what sparks?

To reflect and grow

Capturing and engaging with the ideas and thoughts you have engaged with allows you to codify what is essential to you, giving you a unique place to reflect. A commonplace book can help you find meaning in this world, discover your philosophy of life, and develop your values, leading to a form of self-awareness that can give you a better sense of purpose.

To leave behind an autobiographical account of the things you hold most important

Like it or not, we all will die eventually. When we do, our loved ones will have the bittersweet job of going through our possessions. A commonplace book is one of the most incredible things we can leave for them to find. Compiling our thoughts on the subjects we care about can open a window into who we truly are. To be able to do that for those we love most is a wonderful final gift.

How to get started with one?

There are countless examples of commonplace books. Spend 15 minutes browsing the Commonplace Book Reddit community, and you’ll find some inspiration. Here are some valuable tips to help you get started with your practice:

Decide on your medium: Choose something that fits your preferred writing style. A physical notebook, digital software (such as Notion, Evernote, or Obsidian), notecards, or a hybrid model of all of these can work fine. The specific choice doesn’t matter — what does is that your method best suits your lifestyle.

Develop a system for capture and organization: You’ll need some process that helps you determine what goes into your book (capture) and how to store it for later recall (organization). Coming up with this idea upfront will save you time later on. You can use John Locke’s method, Ryan Holiday’s notecard system, or create your own. Again, what matters is that you have a system, not which one you use.

Capture wisdom, not facts: Google is for facts. Your commonplace book is for knowledge. You don’t need it to help you remember dates or random pieces of information. Use it to store valuable insights that you accumulate throughout your life.

Keep it handy and enter into it regularly: Mine is always by my side, even when traveling. I dedicate time to my practice every Sunday during my weekly review session. I synthesize my notes from the prior week and determine what (if anything) to enter.

Don’t worry about changing it: Your medium, system, and interests may change over time. That’s okay. We all change as people. This is natural and means that you’re growing. Your commonplace book can evolve with you.

My final advice is to get started and not overengineer it. Too often, we have an idea but think we must plan everything perfectly before digging in. This can paralyze us, leading to inaction.

Start by creating a list of topics you care passionately about and gathering some primary research. Keep a highlighter or pencil handy, and capture passages you like. Then, enter what resonates into a notebook. Did you do that? If so, congratulations, you just started your first commonplace book.

My Commonplace Book

I started my commonplace book journey last year and am still working through my first book. While I would not consider myself an expert, below is my process, which has worked so far.

I use a physical notebook — I purchased this one from Amazon. While I use digital software for many things, I enjoy the feeling of paper and pen for this practice. There’s evidence that we remember things better when we write. I chose a dotted grid notebook; it gives me the flexibility to include any content (e.g., words, graphs, drawings, etc.) while still maintaining spatial structure.

Digital software can work. However, if this relic is meant to be passed along, I worry about the lasting effect of notes stored on a computer or cloud server. If I were to die tomorrow, my family would go through any physical notebooks. On the other hand, my entire Notion database would probably be left unread and disappear into the ether.

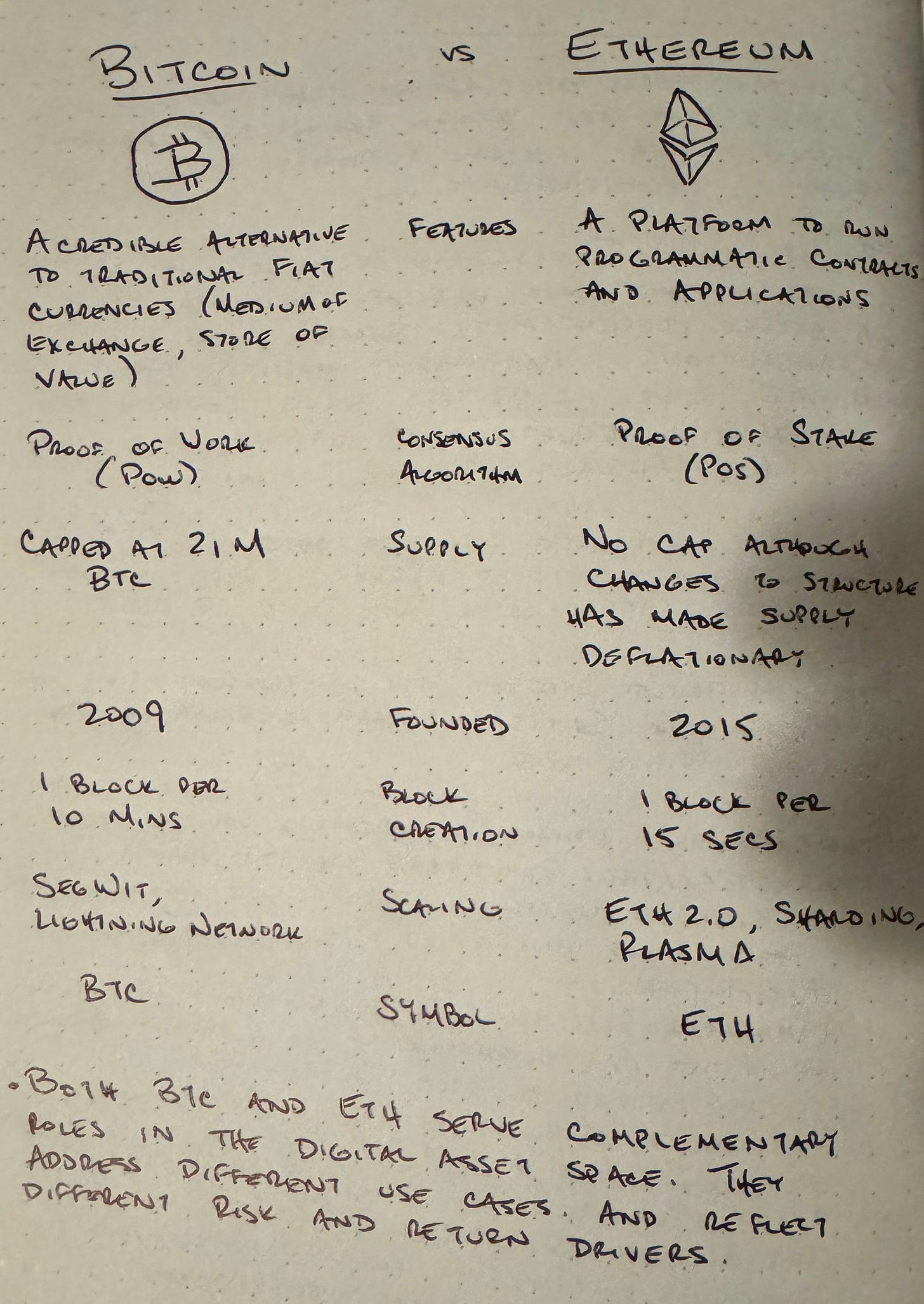

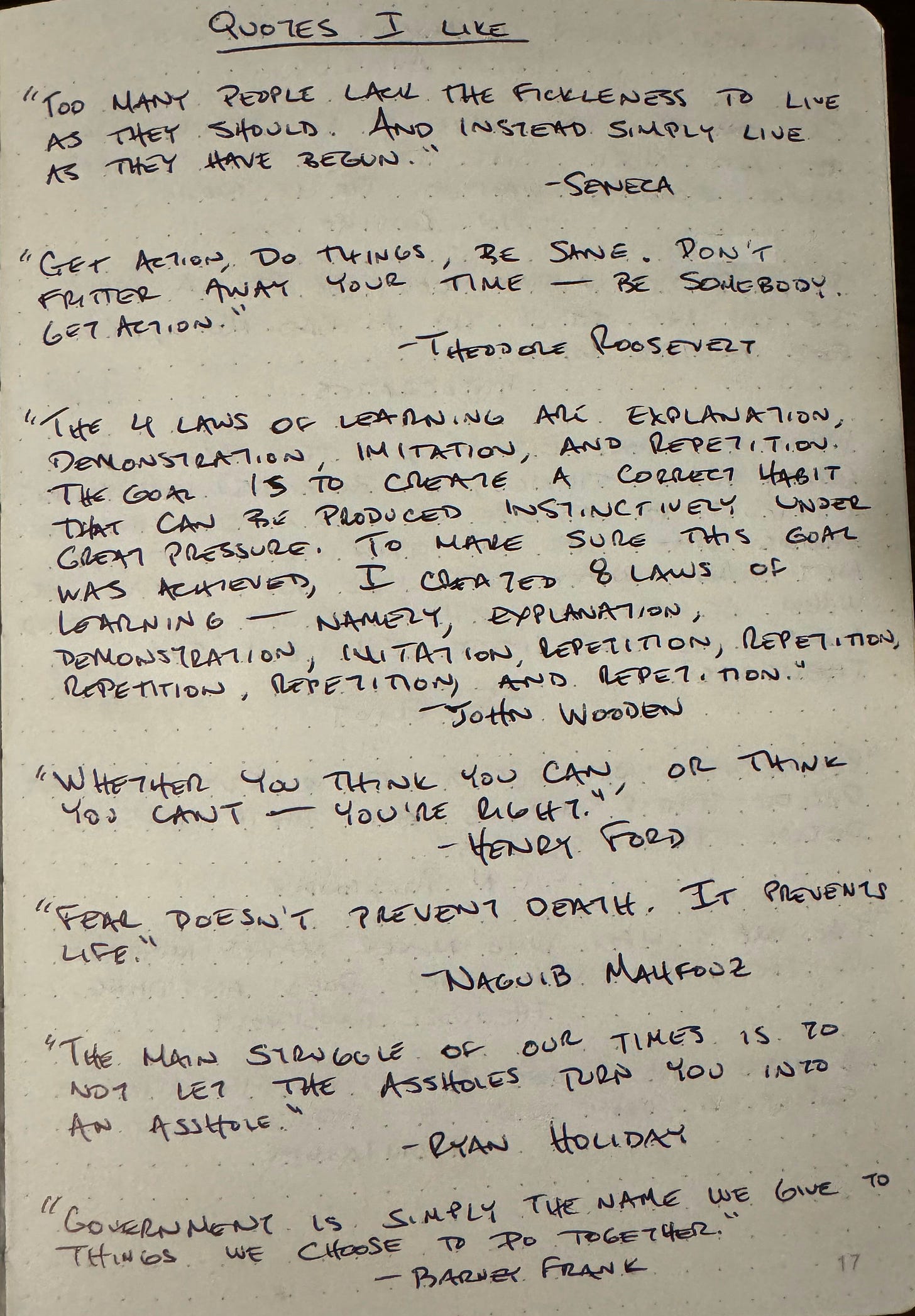

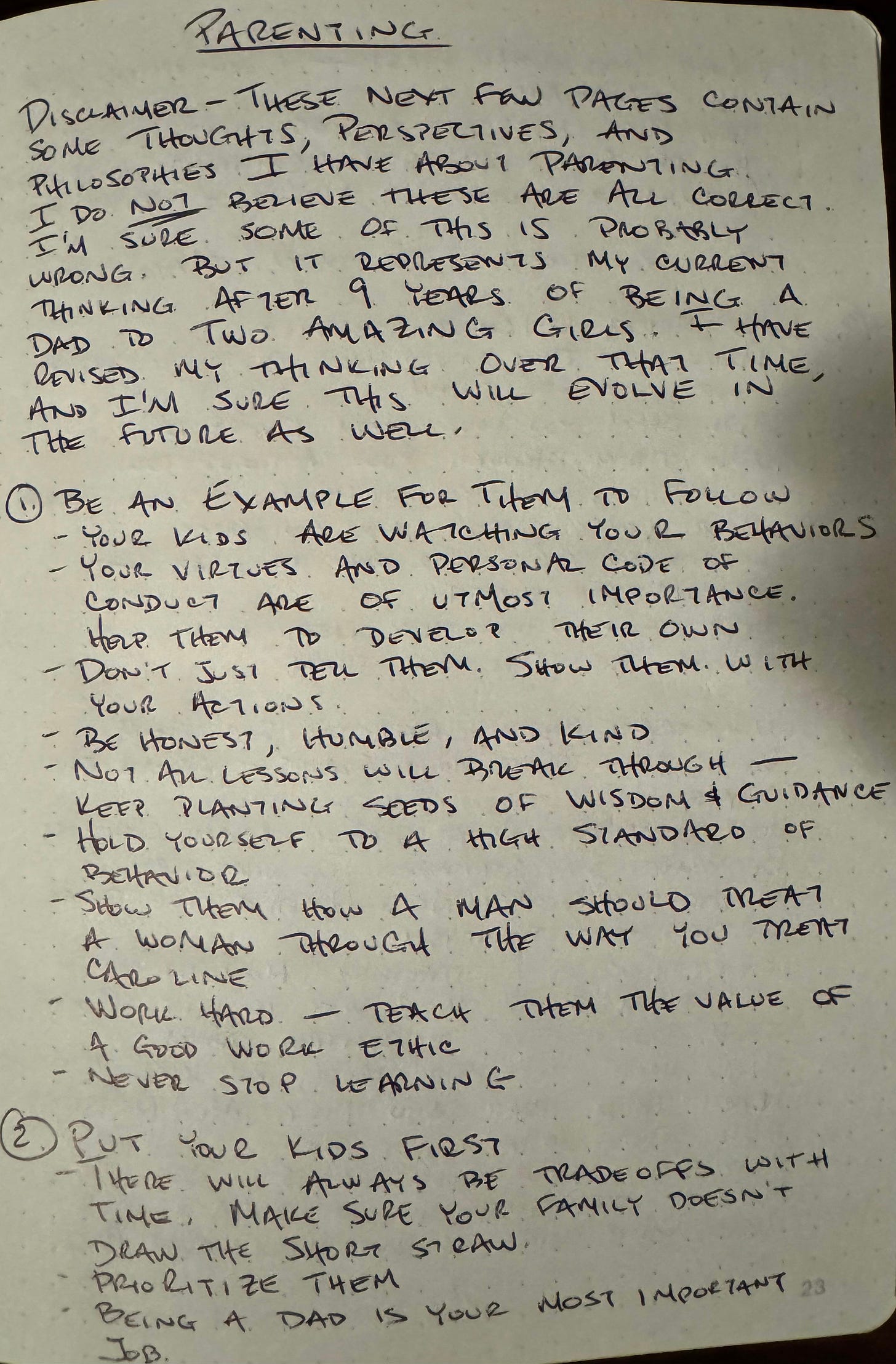

I compile the information about areas that interest me into my commonplace book. Some topics in my notebook include Stoicism, cryptocurrency, AI, fitness & nutrition, parenting, marketing, data & analytics, productivity, miscellaneous quotes I like, and other broad concepts I find interesting (e.g., exponential growth, variance, etc.).

My commonplace book is not my primary notebook. I still have several “front-line,” less organized notebooks for various purposes. I keep one at my bedside, one in my garage, one in my car, and one at my desk for general thoughts that come to mind. I also use Notion for day-to-day notes and task management. I have no filter for what goes into these notebooks; they are meant to capture everything.

During my weekly review session, I reserve time to enter things into my commonplace book. I reread the jumbled notes I wrote within my “front-line” systems the previous week and distill the essential ideas and concepts. I then transfer a small subset of what’s there, usually rewritten with my own words and thoughts, into my commonplace book.

If the content is related to an existing topic, I’ll add it to that section of the book if space is available. If there isn’t additional room in the section I’ve previously written or it covers a topic I have not written about, I’ll add the content to the next blank page. The book’s first few pages contain an ad-hoc table of contents, where I list the topics and associated page numbers. I update this as necessary when I add new material.

Below are pictures of a few of the pages from my notebook:

I’m not suggesting this is the one way to go. I’m sure there are many ways I can and will improve this process in the future. The point is that I’m going through this exercise and doing it, and it works for me now.

It’s the process that’s making me better. At the end of the day, that’s what it’s all about.

Conclusion

I’m still early in my commonplace book journey, but I can already say that integrating this into my life has been incredibly beneficial.

Like many, I have felt overwhelmed by the bombardment of information. There is too much to process between the books I read, podcasts I listen to, web articles I browse, and random nuggets of wisdom that occasionally make it into my social media feed. I struggled to keep up and didn’t know how I could ever expect to retain anything.

Building a process to capture this information, organize it into something I can access later, and distill my thoughts helps me better express myself throughout my life (shout-out to Tiago Forte and his CODE framework). I feel less cluttered, knowing I have a system to ingest the essential things I consume. As a result, I stay more present, significantly impacting my personal growth, well-being, and relationships with my family and friends.

I highly recommend that you try this out for yourself. Commonplacing is a practice that can help people of all lifestyles. Don’t put it off or try to plan it perfectly. Just start — and keep going. Trust me, it’s worth it.

If you have a common book practice, please share it in the comments below. I’d love to hear about it.

You should also check out the Commonplace Reddit channel. It’s full of outstanding examples that have inspired me.

If you like what you read today and want these posts sent directly to your inbox, please subscribe to my mailing list. Future posts will vary in focus — you can read more about the topics I write about here. New essays are written approximately twice monthly.

Good luck if you choose to start your commonplace journey. I’ll be back with another essay in mid-February.

All the best,

Lukich

Hi! I’m a huge fan of your YouTube videos and I would gladely pay for your solver school although it is inactive right now. Feel free to reach out to me if that would be possible. I can pay through any platform you prefer.