How long should CPR be performed after cardiac arrest in the hospital?

A series to help inform the final life-and-death decision

This is the first of a series of articles on the duration of CPR for in-hospital cardiac arrest. Read the whole series:

Introduction

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is performed on more than 250,000 people in U.S. hospitals each year. When a patient is failing to recover spontaneous circulation, the clinician in charge must decide whether and when to cease resuscitation efforts. Moments after he or she says “stop,” the person will be declared legally dead.

It’s an awesome and humbling responsibility, the ultimate life-and-death decision.

Yet physicians receive no formal guidance or training on how, when, or why it should be made.

How do physicians and providers decide to stop CPR after in-hospital cardiac arrest—and how should they?

Silent Guidelines, Clinical Variation

The American Heart Association publishes voluminous guidelines on how CPR should be performed and closely controls the process of CPR training and certification. However, AHA’s guidelines are notably silent on how long to perform CPR.

Without guidelines or established professional norms, physicians have a high degree of autonomy in deciding how long to perform CPR. Lacking evidence to guide their decisions, they typically default to heuristics acquired during training or from the local culture in their health systems.

This allows for flexibility in treating individual patients, but also results in wide variability in the observed duration of CPR after in-hospital cardiac arrests.

For example, among 45,500 in-hospital cardiac arrests between 2001 and 2010, the median duration of CPR among the patients who did not achieve ROSC (i.e., who died) was 21 minutes. But the range was broad: 25% were coded for less than 13 minutes, and 25% for more than 30 minutes.

The major factors associated with a longer duration of CPR were patient age (odds ratio 1.8 for age <65) and the placement of an advanced airway (odds ratio 2.6).

That data also produced an interesting signal: hospitals with the longest durations of CPR on average—at least 25 minutes in most patients—also had higher rates of ROSC and survival to hospital discharge (both odds ratios ~1.1).

It’s unclear whether those improvements were due to the longer CPR itself or unmeasured factors (confounders) like healthier patients or better cardiac or critical care.

If longer CPR does lead to improved survival with acceptable neurologic outcomes, should a specific duration of CPR be recommended?

And if CPR is futile past some identifiable period, should there be a maximum duration of CPR for most patients?

Duration of CPR’s Relationship to Outcomes

The relationship between the duration of CPR for in-hospital cardiac arrest and outcomes was best explored in an analysis (Okubo et al., BMJ 2024) of a large registry of ~350,000 hospitalized U.S. adults who underwent CPR between 2000 and 2021 at hospitals participating in the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines program.

That data provided the most comprehensive picture to date on survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest:

Overall, two-thirds (67%) of patients undergoing CPR recovered spontaneous circulation (i.e., survived CPR).

However, about two-thirds of those patients who survived CPR died in the hospital before discharge.

That left less than one-quarter (23%) who survived until hospital discharge after in-hospital cardiac arrest.

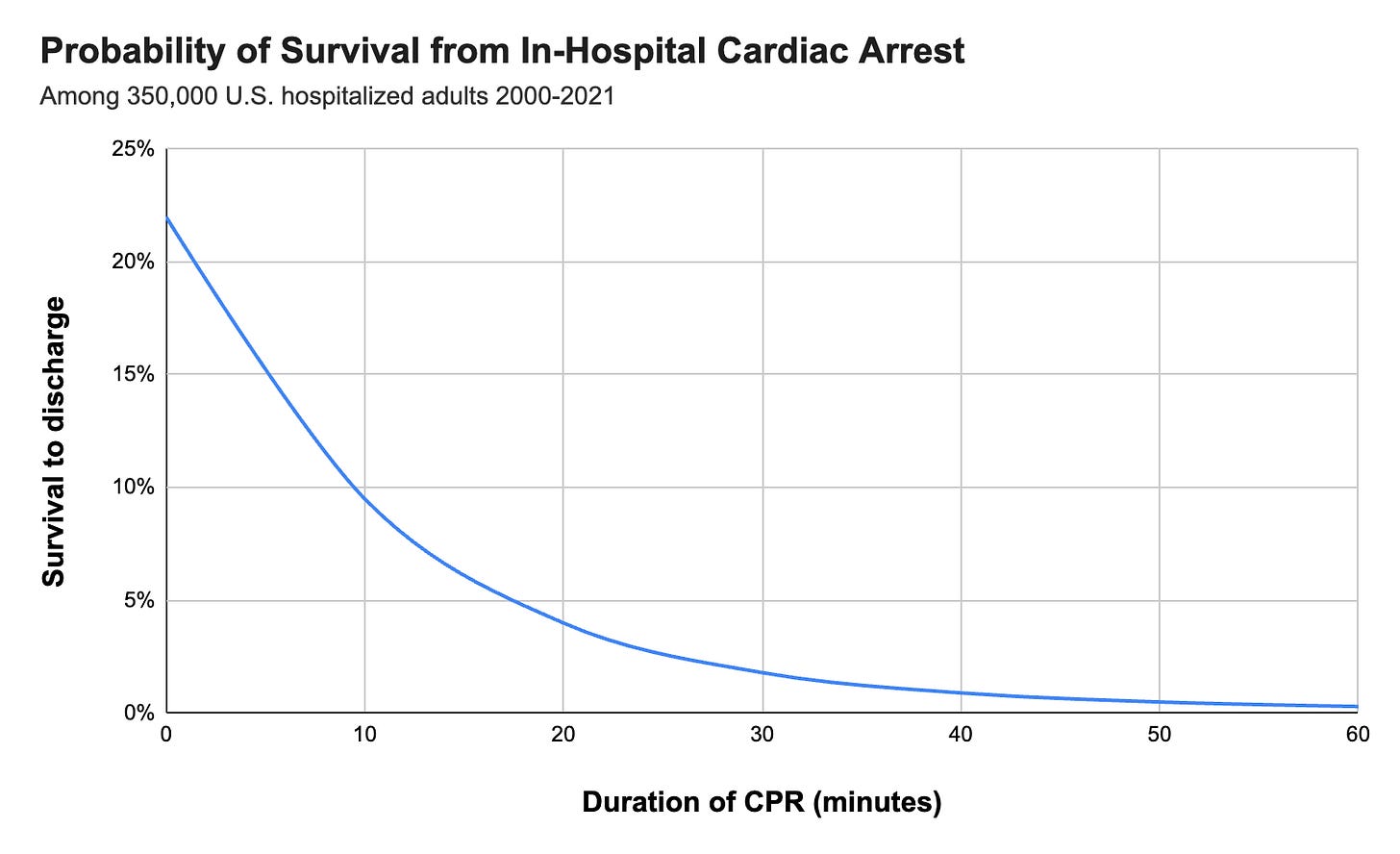

Survival to hospital discharge declined with longer duration of CPR in a nonlinear fashion:

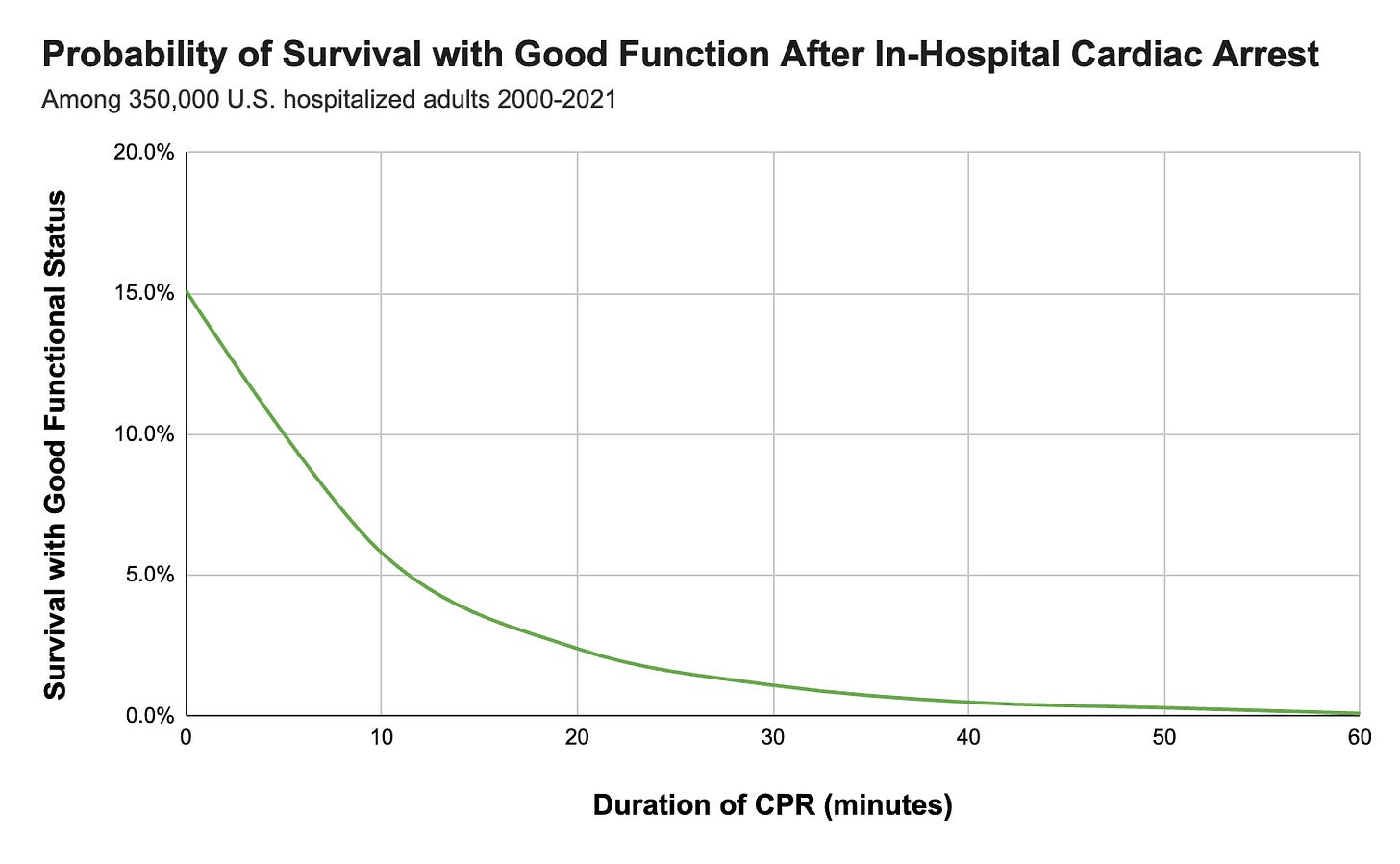

About two-thirds of those surviving to discharge had good functional status (able to live independently, with mild-to-moderate disability or no disability). Survival to hospital discharge with good functional status likewise declined with longer durations of CPR:

(If you’re reading this in an email, click the post title for a better view of the plots on the website or app.)

Much More to the Story

These plots hide enormous variation and complexity among the patients experiencing in-hospital cardiac arrests, which we will explore in detail in this series of posts on CPR:

Outcomes after CPR for arrests due to “shockable” rhythms (ventricular fibrillation and tachycardia) are much better than those due to “non-shockable” rhythms (pulseless electrical activity and asystole).

Patients with witnessed cardiac arrests have better outcomes on average than those with unwitnessed arrests, thanks to faster initiation of CPR and better-resourced care environments.

Younger patients’ outcomes after in-hospital cardiac arrest are significantly better than older patients’, on average.

Clinicians understand all this intuitively, but the most recent data permit us a granular view of these variations and their implications for individualized patient care decisions.

Potential Risks and Harms of CPR

CPR can be lifesaving and it should be performed to the maximally beneficial extent on all patients who have not explicitly declined it (directly or through their surrogates).

It’s also an aggressive, frequently injurious procedure that ideally should not be performed beyond the point of potential benefit.

CPR can result in survival with severe neurologic injury or disability that may not be acceptable to some survivors. (This is a complex area, as some severely disabled people report a higher-than-expected quality of life after a period of adjustment.)

Health professionals who repeatedly perform CPR perceived as excessive or futile may experience reduced job satisfaction and well-being.

A Look Ahead

Clinicians perform CPR on thousands of patients every day in hospitals around the world.

The technical aspects of the procedure are meticulously taught and tested. But as for the important question of how long to perform CPR, physicians and providers are on their own.

Recent data can help inform this challenging decision, allowing clinicians to develop rational and caring heuristics that can then be tailored to individual patients.

In the coming weeks, we’ll take a deep dive into these data and what they mean for clinical practice.

Codes will always be intense—as the adage goes, the first thing to do is to check your own pulse. This series will try to help with the last part: ending resuscitation efforts, knowing you did your best.

References

Okubo M et al. Duration of cardiopulmonary resuscitation and outcomes for adults with in-hospital cardiac arrest: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2024;384:e076019

Thank you for your take on this complex topic. I haven’t looked at the research, but has bedside US (quick look) impacted the duration of CPR efforts? Keep up the amazing work.

Great analysis and thanks for expounding upon the previous CPR piece. So much of ICU medicine seems to be fighting like crazy for the certain percentage who might actually pull through. It’s sobering when you see that some patients get long CPR and still make it through. Not sure what that percentage might be or the ancillary cost of anoxic but hemodynamically stable patients might be, but it’s great that someone is looking at data here.