Professor Donald Shoup died on February 6th. M. Nolan Gray explains how his mentor changed political economy of parking, and cities themselves, forever.

As we might say in Los Angeles, Donald Shoup was a professor out of central casting.

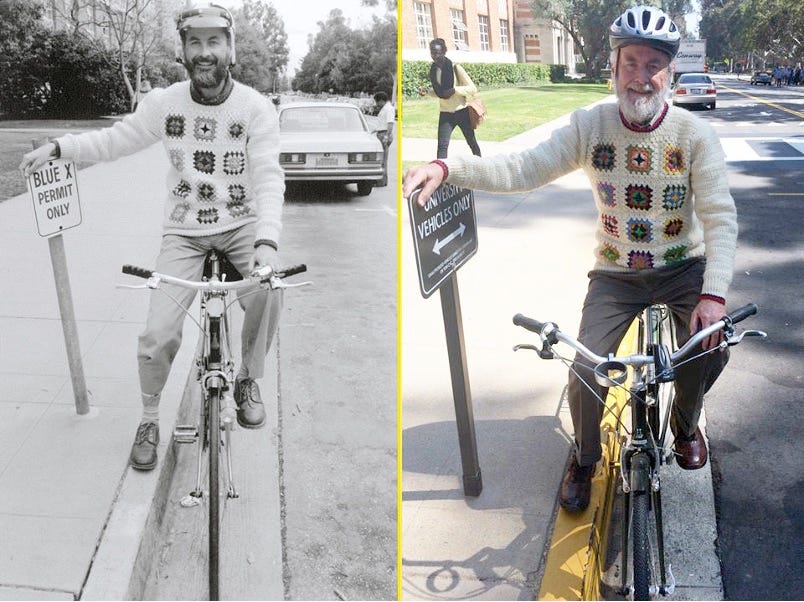

His wardrobe consisted of tweed sport coats, earth-tone khakis, and unfashionably broad ties. He had a long, scruffy beard and spoke in a plodding, measured way. His stalling quirk was a long, ponderous ‘well, yes…’. For much of his career, he biked to campus. From his stuffy office on the fifth floor of the Luskin School of Public Affairs at UCLA, he had chosen to make parking the focus of his studies—an impossibly boring topic, even by the low standards of a city planning department.

Yet by the final accounting, Shoup has a strong claim on being the scholar who will have had the greatest impact on your day-to-day life, radically changing how we approach the unglamorous problem of how and where we park our cars—and, in turn, where we can live, how we move about, and the form our cities take.

Inspired by his work, San Francisco formally adopted demand-based pricing for curb parking in 2017. That same year, Hartford and Buffalo abolished minimum off-street parking requirements citywide. In 2022, California abolished them within a half-mile of transit statewide; around the same time, New Zealand abolished them nationwide. With religious zeal, an army of self-identified shoupistas has gone on to implement his ideas in thousands of cities across dozens of countries—and this is likely only the beginning.

The old professor resisted attempts to hitch his ideas to any particular creed—except Georgism, that school so preoccupied with how we price land. Parking reform is neither conservative nor progressive, neither libertarian nor socialist. (It’s all of these things, Shoup certainly would have argued.) He definitely wouldn’t have identified as a Marxist. And yet, he fully realized that old exhortation from Marx that ‘philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.’

In a world full of professors with fine enough ideas, what made Shoup different?

The premise of The High Cost of Free Parking, Shoup’s 800-page magnum opus, is as simple as it is provocative: parking is nearly always too cheap.

An unfortunate fact about cars is that they occupy a lot of space. Worse yet, they only spend about five percent of their lifespan in motion. The remaining 95 percent of the time, we must find a place to put them. When Americans first started buying cars en masse in the early twentieth century, the solution seemed obvious: park them along the curb. In the most radical shift in city planning in human history, urban streets—once the site of gathering, selling, and playing—were redesigned around moving and storing cars.

The result was a classic ‘tragedy of the commons’ situation: When a good is unpriced, we naturally overconsume it. In pure economics terms, the demand for a good at a price of zero nearly always exceeds the supply, resulting in scarcity. Hence, the ‘tragedy.’ In the case of curb parking, unpriced curbs rapidly fill up with cars whose drivers have no incentive to free up space. Thus, the state of a typical residential street: a travel lane or two framed by two parking lanes lined with cars that rarely move.

All of this ‘free’ curb parking is hardly free. Rather, the typical driver must instead spend time cruising around, looking for parking. One survey of the literature suggests that drivers in the typical American city spend an average of eight minutes looking for parking at the end of each trip. If a driver makes seven trips like this a week, she will waste nearly 49 hours each year merely looking for parking. If she values her time at the median US hourly wage, these delays will cost $1,898.75.

The hidden costs of ‘free’ curb parking only start there. The same surveys suggest that around a third of all drivers in the typical American city are actively cruising for parking. The share is likely even higher in dense residential neighborhoods like South Philadelphia or Boston’s Back Bay. If we could flip a switch and reduce traffic by 30 percent—with all the attendant costs to air quality, street safety, honking, wasted time, and street damage—we would almost certainly do it.

As the token economist in UCLA’s planning department, Shoup recognized the solution: price the commons. If you set a high enough price, at least one spot will always be available. Nobody will have any incentive to waste their time cruising. Better yet, if prices can fluctuate in response to demand, drivers will be incentivized to adjust their trips efficiently. Those with options could instead take the bus, minimize driving at peak times, or park a little further away and walk the rest of the way. Thus, the demand and supply would naturally equilibrate.

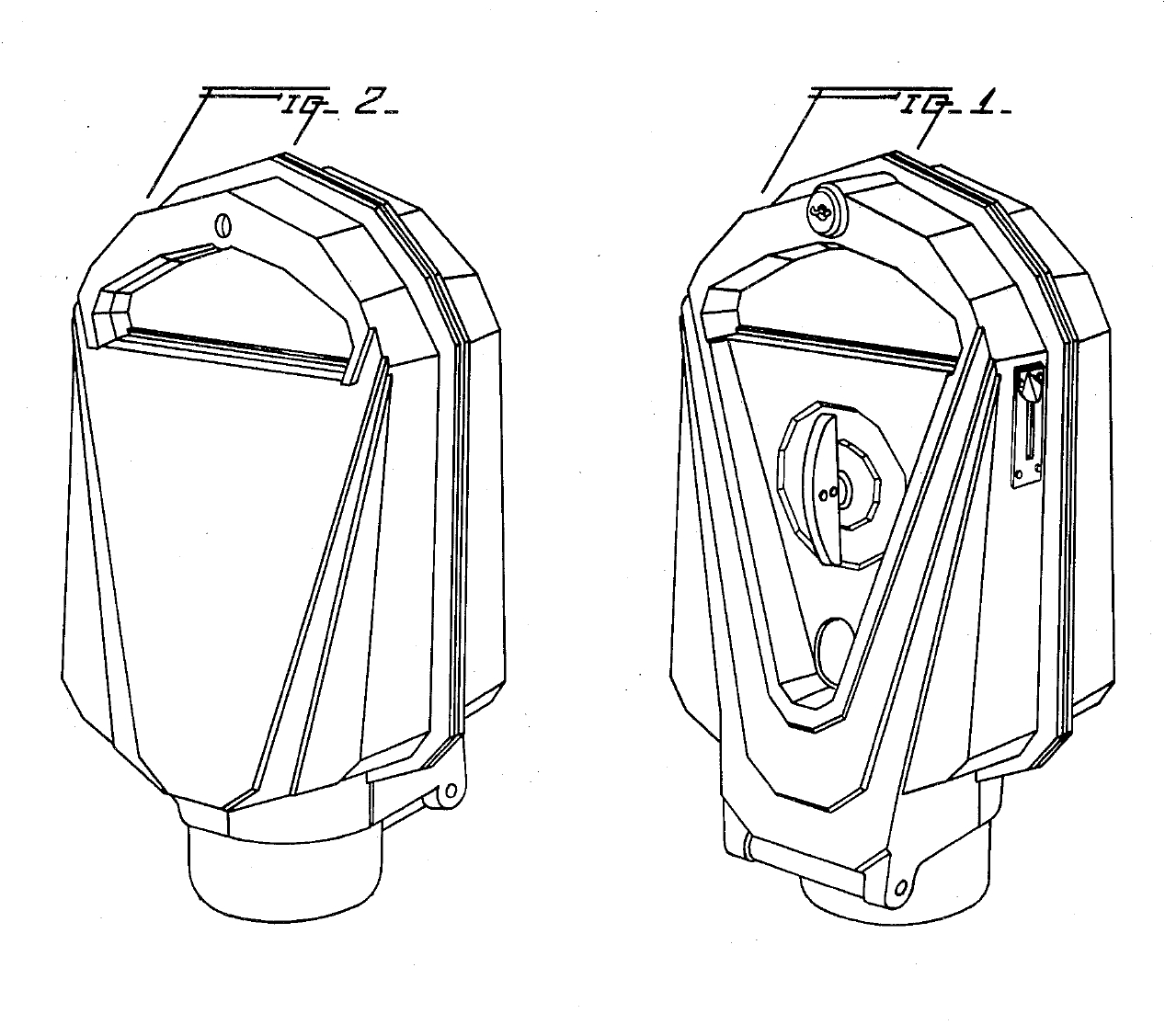

In fits and starts, cities have tried to price curb parking. In 1935, Oklahoma City installed a newfangled device called the ‘Park-O-Meter’ at the behest of downtown merchants with a financial interest in parking turnover. Absent pricing, commuters would fill up the spots each morning, boxing out shoppers. Yet properly priced curb parking remains the exception. The vast majority of curb parking remains ‘free.’ In New York City, where every square inch of land is enormously valuable, 97 percent of curb parking is unpriced.

Why? In the Seinfeld episode aptly named ‘The Parking Space,’ George balks at Elaine’s suggestion that he pull into a paid garage rather than waste time cruising. ‘It's like going to a prostitute. Why should I pay when, if I apply myself, maybe I can get it for free?’ To the extent homo sapiens falls short of homo economicus, the politics of pricing curb parking are bleak. We struggle to make sense of the time value of money and hate paying for something we had thought of as free—even if doing so would improve our lives. (Not to imply that you should pay for sex.)

Instead, American city planners turned to minimum off-street parking requirements, ‘solving’ the parking problem by mandating that vast amounts of it be built as part of any new residential or commercial development. In 1923, Columbus, Ohio, became the first city to require that any new apartment building provide each unit with at least one off-street parking space. Over the next century, such mandates rapidly spread worldwide, becoming a mainstay of modern land-use planning.

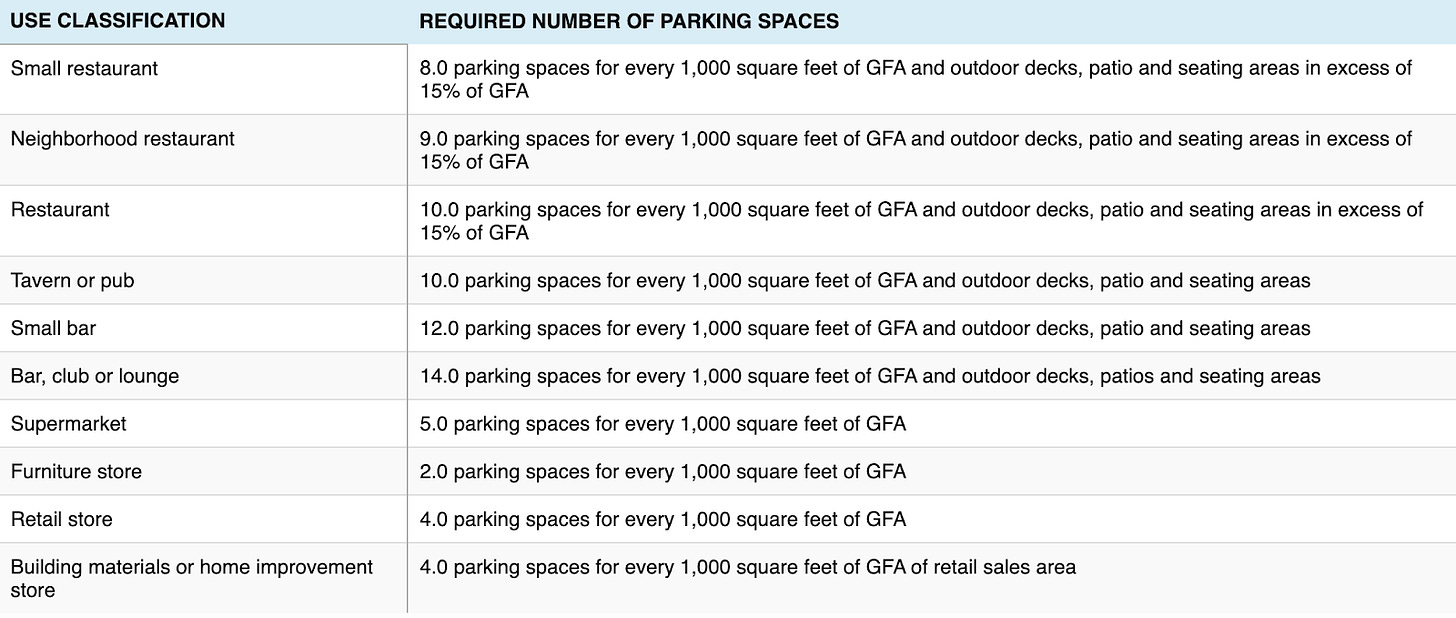

Today, residential developers are nearly always required to supply one parking space per housing unit. Commercial developers must build anywhere from 2.5 to 10 parking spaces per 1,000 square feet (93 square meters) of office or retail space. These rules are frequently amusing in a byzantine way: In one city, gyms must provide one parking space for every 2,500 gallons of water in a pool, as if deeper pools invite more patrons. In another city, nunneries must provide one parking space for every 10 nuns. What happened to church vans?

Most cities set their requirements based on the Parking Generation Manual, a $500 tome published by the Institute of Transportation Engineers. The book estimates parking demand for everything from airports to wineries. At first blush, it seems very scientific, replete with charts, numbers, and statistical jargon. But the typical estimate in the Fifth Edition is based on fewer than 10 observations, often with no clear correlation—that is, pseudoscience. If you submitted such work as part of an introductory statistics course, the professor would likely ask you to come to his office hours. And yet it became official policy in cities the world over.

Nor are minimum parking requirements even needed: developers have the knowledge and incentives to provide the appropriate amount of off-street parking. If a developer builds too little parking, she will struggle to attract tenants and command lower rents. If she builds too much parking, she will find she cannot compete with other developers on cost. In contexts where no minimum requirements exist, but parking is still needed, developers virtually always provide it. For all their faults, markets have a way of solving issues like this.

The practical effect of these requirements is to force the construction of far more off-street parking than could ever conceivably be necessary. As the Strong Towners have long documented, suburban shopping mall parking lots are so cartoonishly overbuilt as a result of minimum off-street parking requirements, that they usually sit empty even on Black Friday, the busiest shopping day of the year.

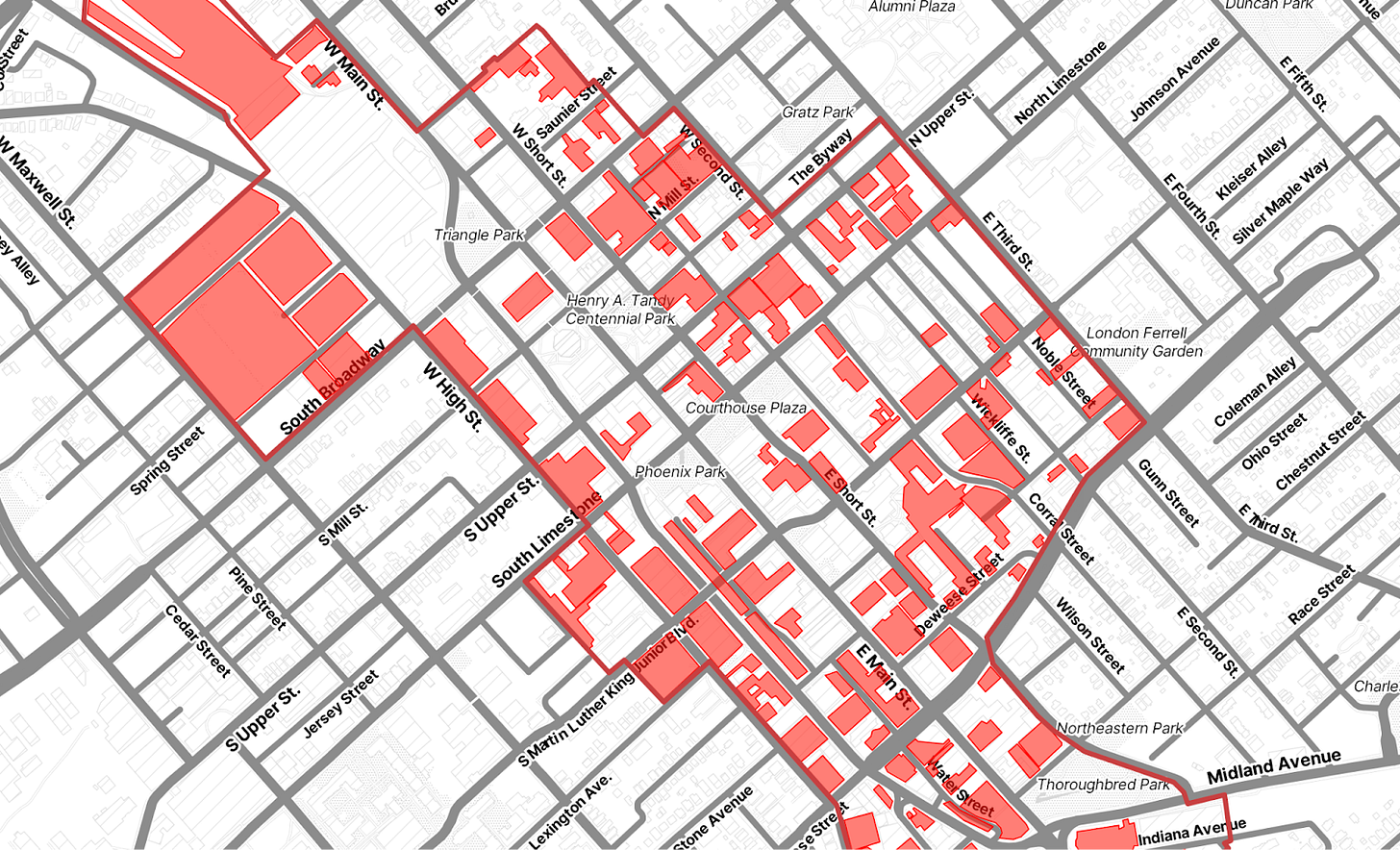

Minimum parking requirements might seem innocuous. But it’s hard to overstate the deleterious effect they’ve had on the form of our cities. In neighborhoods built before the car, they made a wave of demolitions legally necessary. Today, over a third of the typical American downtown is now taken up by surface parking lots—and that’s before considering parking garages. In the suburbs, built out consistent with these rules, the result is a landscape of garden apartments, strip malls, and office parks surrounded by acres of parking lots that are virtually never full.

Of course, none of this off-street parking is ‘free’ either. All of this parking takes up space and increases development costs. In the worst case—as with the adaptive reuse of historic buildings or the construction of infill housing—it may make development altogether infeasible. In the best case, it merely makes development more expensive. Estimates vary, but each additional parking space adds as much as $20,000, $50,000, or $80,000 to the cost of a project, based on whether it involves a surface lot, above-ground garage, or below-ground garage, respectively.

These costs don’t magically disappear. Instead, they translate into higher prices. You might think that Whole Foods parking spot was free, but you can be sure you’re paying for it in more expensive groceries. The impact of minimum parking requirements on housing affordability has earned them the special ire of YIMBYs, who would like to see higher rates of construction and lower prices.

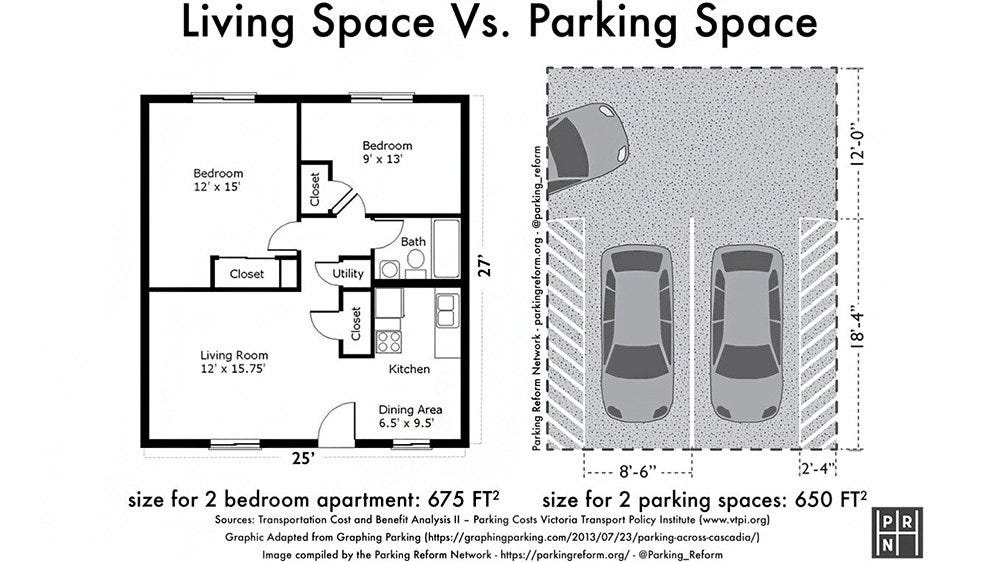

To understand why, imagine a 675 square foot (63 square meter) two-bedroom apartment—hardly glamorous, but the sort of accessible housing many cities need to get costs under control. In much of the US, a developer could profitably bring this unit to market for under $300,000. But if the city imposes a parking requirement of two spaces per unit or one space per bedroom, it could increase the cost of the unit by as much as a third, requiring future residents to consume as much parking space as they do living space. Many families might happily make that tradeoff. But the thing about a requirement is that you don’t have a choice.

Indeed, the most pernicious thing about these requirements is that they write automobile dependence into law. Perhaps most people like living amid vast parking lots and towering parking garages, spending thousands of dollars each year to shuttle themselves by car. Perhaps nobody wants a smaller, more affordable apartment in a neighborhood where they can safely walk to a storefront café or barbershop, or hop on a subway downtown. Less sophisticated observers insist that everything that exists is merely what consumers prefer. But in a world without choices, who is to say?

At this point, the typical policy essay would end: In my infinite wisdom, I have shown yet another way in which the world is bad. But I’m sorry to say that the politics of this suboptimal equilibrium are solid. Unfortunately, it’s all too easy for planners to keep curb parking ‘free,’ no matter the harm, while mandating the construction of endless ‘free’ off-street parking that will quietly increase costs in every other aspect of life. Oh, well.

But that’s not where our story ends. In 2005, Donald Shoup published The High Cost of Free Parking. As an academic treatise, it’s a profoundly weird text: the obligatory scholarly patter about what we still don’t know is absent. The wonky theory, supply-demand curves, and tables of figures are all there, but they’re punctuated by jokes, media snippets, personal anecdotes, and more than a few peculiar allegorical digressions. Taken collectively, it’s the closest a city planning textbook will ever come to House of Leaves.

It is also strikingly practical. Shoup empathized with the plight of the typical planner: Yes, we know that minimum off-street parking requirements cause all sorts of problems. But if we don’t impose them, we’ll need to price curb parking to avoid a tragedy of the commons situation—and pricing curb parking is beyond the pale.

His solution to this political problem would end up being his greatest contribution: parking benefits districts. If you take curb parking revenue and invest it in conspicuous local improvements, such as street trees, repaved sidewalks, or regular street sweeping, locals will not only support pricing curb parking—they will often demand it. Once a parking benefits district is established, the politics of pricing curb parking will be secure, and planners can remove minimum off-street parking requirements without fear of backlash.

As Shoup would readily admit, the idea wasn’t handed down from heaven—though Pasadena comes close. In 1993, the city started installing parking meters in what was then a rundown downtown. Customers, merchants, and landlords balked. As a compromise, city leaders agreed to allocate a share of the revenue to local improvements. Streets were repaved, palm trees replanted, graffiti removed, and sidewalks regularly power-washed. Thirty years later, Old Pasadena is one of the poshest shopping districts in North America.

The release of The High Cost of Free Parking in 2005 immediately generated buzz among practicing city planners. By then, Shoup had spent decades training generations of planning practitioners and scholars—including Michael Manville, the current chair of the UCLA planning department—turning parking studies into a lively discipline. In its official timeline, the American Planning Association recognizes the book’s publication as one of the seven most important things to happen in planning over the past 25 years.

Shortly after its publication, Patrick Siegman, a planning consultant and early Shoup acolyte, went on a rant about parking at Zeitgeist, a popular bicyclist bar in San Francisco. His conversation partner, local bicycling advocate Dave Snyder interjected: ‘Oh, you’re just a shoupista.’ The name stuck. A movement had been born. At the depths of the Great Recession in 2008—planners no doubt finding themselves with a lot of free time—a group of shoupistas started a Facebook Group to take turns ranting at each other about parking.

Across California, planners wasted no time rebuilding parking policy along shoupista lines. In 2005, Redwood City overhauled its downtown parking management with the goal of ensuring that at least one or two spaces were always available on each block, eliminating cruising and improving walkability. Closer to home, Ventura started pricing curb parking in 2010, directing part of the revenue into free public WiFi. In Los Angeles, LA Express Park brought sanity to downtown parking in 2012. It was a revolution from above.

In retrospect, these were just a trial run for what would be the most thoroughgoing implementation of Shoup’s ideas: SFPark. Program director Jay Primus’ goal was not merely to install parking meters in a few busy areas. Rather, the goal was to take the program citywide, with prices fluctuating based on demand using sensor-based monitoring. Prices would then be communicated via an app, allowing drivers to make tradeoffs in real time.

The result was a rare win for San Francisco governance: We know from pilot areas that implementing demand-based pricing reduced congestion and parking citations while speeding up transit and increasing overall sales tax revenue. The program is now widely regarded as a model for parking management.

Alongside these California developments, the revolution was being exported, with shoupistas guiding the creation of parking benefits districts in cities like Bangalore, Beijing, and Mexico City.

Then a strange thing happened: normal people started becoming shoupistas. In 2015, a cartoon version of Shoup appeared in an episode of the hit TV show Adam Ruins Everything, making the case against minimum off-street parking requirements. In 2017, a Vox video exploring Shoup’s ideas quickly garnered millions of views. The old shoupista Facebook Group swelled from hundreds of members to thousands, with members producing an endless stream of memes. Shoupistas eagerly shared photos of themselves with Shoup, dressing up as Shoup for Halloween, and their tattered copies of The High Cost of Free Parking.

Back in the real world, the rising YIMBY movement enshrined Shoup as a minor saint and made abolishing minimum off-street parking requirements one of its top priorities. In 2017, the dam broke, with Buffalo, New York, and Hartford, Connecticut, being the first cities to abolish minimum off-street parking minimums—citywide, and for all uses. In 2020, they were abolished nationwide in New Zealand. And in 2022, California abolished minimum off-street parking requirements within a half-mile of transit statewide.

At the time of Shoup’s passing, 99 cities in eight countries had completely abolished minimum off-street parking requirements. Thousands more cities have made incremental progress in rolling back these mandates. In 2019, YIMBY activist Tony Jordan founded the Parking Reform Network, institutionalizing the revolution—and kicking it into overdrive.

In 2005, ideas like implementing dynamic curb pricing or abolishing minimum off-street parking requirements were unthinkable. A mere twenty years later, they now seem inevitable.

Academia is overflowing with hard-working professors with clever ideas that go nowhere. Yet Donald Shoup, perhaps the most unlikely candidate, somehow managed to kick off an international movement and usher in a wave of policy reform. What gives? In my capacity as the teaching assistant for his legendary ‘Parking and the City’ course at UCLA these past four years, I spent a lot of time puzzling over this question. Every quarter I helped teach the course, we had to expand the capacity to let in students desperate to take it. I have come to at least three conclusions.

First, Shoup picked a topic that was simultaneously important, tractable, and neglected. If you ever had more than a 30-minute conversation with him, you no doubt heard the following shoupism: ‘I’m a bottom feeder. But there’s a lot of food down here.’ The way we manage parking is of profound importance to nearly every aspect of our lives. It’s also something local planners have a lot of control over. And yet, before Shoup took up the issue, there was virtually no scholarship on parking—and even less in the way of activism around the issue. We could use a Donald Shoup on many more issues.

The addicting thing about shoupism is that, once you’re on board, you start to see parking everywhere: A story in the newspaper about two drivers getting in a fight over parking? Well, the parking must have been underpriced. (Henry Grabar starts his excellent book on parking by inviting the reader to try to make sense of such a seemingly senseless story.) Finding yourself depressed by yet another town gutted by parking? That’s the minimum off-street parking requirements for you. You know you’ve fully come around when you start taking strange pleasure in paying for parking.

Second, Shoup exercised unparalleled message discipline. He published his first paper on the topic in 1978 and spent the next half-century writing on little else. Aware of the responsibility of his celebrity, Shoup studiously avoided taking a position on almost any other issue. When protesters and counter-protesters flooded UCLA’s campus in response to the Israel-Palestine conflict, I asked for his take. ‘I’m just wondering where they all parked,’ he replied.

Indeed, Shoup worked hard to make his ideas palatable across the political spectrum. Are you a conservative? People should pay for the services they consume. Are you a progressive? All this unnecessary driving can’t be good for the environment. Are you a libertarian? Clearly, the solution to scarcity is prices and markets. Are you a socialist? Let’s stop privatizing the public realm by turning it into a free parking lot. As a result, the typical shoupista gathering is an oasis of peaceful coexistence.

Finally, Shoup built up the next generation. He not only trained many young planning practitioners and scholars—he often bent over backward to help them start their careers. Shoup eagerly responded to emails from planners in even the most unremarkable small towns and often helped young scholars to co-author some of their first research on parking. In his seminars, students were encouraged to publish their work via op-eds or academic papers. Regularly, I hear from former students telling me it changed the course of their careers.

Nor did Shoup shy away from activism: When the aforementioned California bill was in trouble, he sprung into action, calling everyone in Sacramento who would listen. (The bill’s author, Laura Friedman, is now one of at least a dozen self-identified shoupistas in Congress.) In the last quarter Shoup taught, he had students pestering UCLA administrators with memos explaining why they should designate safe parking sites for homeless students. When Los Angeles seemed poised to end a pandemic-era order allowing outdoor dining on parking lots, he worked with former students to make the case against a crackdown.

If you were ever trying to visit Shoup on campus, you probably didn’t need to look up his office number. His was the room with the door covered with newspaper comics about parking—and the source of periodic laughter. When my book on zoning was about to come out, Shoup counseled: when you work on a superficially boring topic, you have to start by making it funny. One of Shoup’s favorite ways to open a talk was by noting that ‘in an audience this large, some of you were probably conceived in a parked car.’

Perhaps being able to laugh at a problem is the first step toward fixing it.