The First Pretty Horse Ain't So Pretty

Cormac McCarthy's All the Pretty Horses: the first sentence

I’ve been writing a series exploring prose style for writers, but here we become readers, examining the styles (and mistakes) of famous books. We begin with Cormac McCarthy and All the Pretty Horses.

But let’s take care of some business first—in 4 parts:

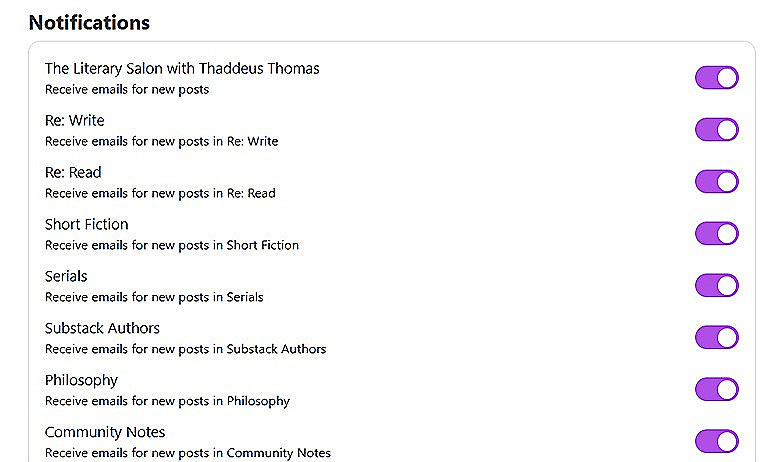

1. Easily Manage Your Subscription

Every Section has a toggles. Toggle on the ones you want to receive and toggle off the ones you don't.

go to: https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

That’s https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

2. Grab a Free Book and Support our Promotional Efforts

Visit the Totally Awesome but Very Humble Authors promotion.

3. A New Private Newsletter for Bookmotion Members

I’ve opened a private newsletter to help simplify communication. Bookmotion members, please visit news.bookmotion.pro and subscribe.

4. Not yet subscribed to Literary Salon?

Some of my essays are for paid subscribers only.

And now let’s talk about All the Pretty Horses

The Grady name was buried with that old man the day the norther blew the lawnchairs over the dead cemetery grass. The boy's name was Cole. John Grady Cole.

All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy

Now that I’ve moved The Last Temptation of Winnie the Pooh to Literary Salon, it’s being rediscovered, and I’m once again struck and honored by the comments saying I’ve captured the style of A. A. Milne and the original stories. The striking part is that no caveat is given for those aspects inspired by or paying homage to Cormac McCarthy—particularly Blood Meridian.

The opening line of the story—Behold the bear—echoes the opening of Blood Meridian—See the child. There are times when the inspirations flow back and forth, and while the wording is clearly outside of the normal Pooh tale, the voice isn’t lost.

The bear hears only the nothing-noise and nothing else in the whole wide Wood. Even the birds have taken the brethern’s vow of silence.

Later in the book, perhaps the reader notices this pastiche:

Once, they were dancing, and the ground beneath them danced too. Towering over them all was Christopher Robin, lively and quick. His mother said it’s bedtime, but he said he never sleeps. Yes, he said, he never sleeps, and Pooh never sleeps because he’s made of fluff, and Christopher robin wanted to be made of fluff, because Pooh, he said, will never die.

And Christopher Robin would never die. He said he’d never die.

McCarthy’s rhythmic quality of the writing and the stretches of short sentences, create similarities with Milne’s classics for children, and this is where my thoughts lie as I approach the prose of All the Pretty Horses.

The First Pretty Horse Ain’t So Pretty

The candleflame and the image of the candleflame caught in the pierglass twisted and righted when he entered the hall and again when he shut the door. He took off his hat and came slowly forward. The floorboards creaked under his boots. In his black suit he stood in the dark glass where the lilies leaned so palely from their waisted cutglass vase. Along the cold hallway behind him hung the portraits of forebears only dimly known to him all framed in glass and dimly lit above the narrow wainscotting. He looked down at the guttered candlestub. He pressed his thumbprint in the warm wax pooled on the oak veneer. Lastly he looked at the face so caved and drawn among the folds of funeral cloth, the yellowed moustache, the eyelids paper thin. That was not sleeping. That was not sleeping.

This does not sound like Winnie-the-Pooh, nor was that my point. Instead I had in mind Brooks Landon’s notion that there isn’t much an author can do with a short sentence, stylistically, and I’ve prickled at the idea, certain that authors can and must impose their style upon writing that embraces the shorter sentence. Milne does it, as does Hemingway. The question is only in how.

The answer isn’t that much different from the long sentence, where Landon’s beloved cumulative sentence creates its style one clause or phrase at a time, so must it be for every Hemingway—one sentence at a time. Punctuation is never a hard stop on style, if one chooses to use punctuation much at all.

McCarthy begins the novel with complex imagery and then follows that up with a simple and easy: He took off his hat and came slowly forward. In fact, the entire paragraph is written in brief sentences punctuated by three longer ones at the beginning, middle, and end, like signposts of the paragraph’s structure.

McCarthy begins with something Landon would warn against, a compound subject which does nothing to help the sentence move forward. That subject is: The candleflame and the image of the candleflame caught in the pierglass.

A pierglass is a tall mirror that’s usually placed between to windows, which was a definition and a word unknown to me. I’d just finished work on a story that takes place upon a ship, where the lanterns are fashioned to remain upright as the ship rocks, and I had this in mind as I read the sentence, not understanding that the air pressure of the door’s movement bent the flame of the candle and of the candle’s reflection.

Because I couldn’t ground myself in that first sentence, I was still trying to catch up for the next several and missed the point that the hall is decorated with portraits of the boy’s ancestors. This isn’t a funeral home but the his grandfather’s ranch house. I did at least understand that the man was dead.

I’ve taken Blood Meridian, The Road, and Cities of the Plain down from my shelves. All three have opening sentences that are easy to understand.

They stood in the doorway and stomped the rain from their boots and swung their hats and wiped the water from their faces.

Cities of the Plain by Cormac McCarthy

It may be that Pretty Horses confused no one else, and I’m just a fool. For the moment, I’ll assume otherwise.

It’s the compound subject that creates my confusion, as I could easily deal with not knowing what a pierglass was. I thought the pierflass was a window set in the door, and as the door opened, the angle of the glass twisted its image, which it wouldn’t do, nor would it affect the actual candle flame even if it did—no matter. No, the confusion is in the subject, in trying to capture within that subject its reflection in the mirror.

With the subject simplified, the sentence reads like this:

The candleflame twisted and righted when he entered the hall and again when he shut the door.

It’s a fool’s errand to find fault with a classic writer like McCarthy, especially one whose work you love, but this isn’t a good sentence, let alone a good opening. The subject isn’t confusing merely because it’s comprised of twelve words;—I initially assumed caught was the verb, not merely part of the ongoing subject. 1

When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he’d reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him.

The Road by Cormac McCarthy

I can’t remember ever running into a complex subject in any of McCarthy’s other books, at any point, not that I’ve gone back and looked, except for these three opening lines.

See the child.

Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy

Complex sentences are good, but I’m going to have to agree with Brooks Landan on this one; extreme versions of a complex subject are not.2

Let’s take our definition and examples from Snap Language. 3

Articles, adjectives, phrasal verbs, and even embedded clauses can be added to the simple subject. The resulting construction is called a complex subject.

“Learning takes a great deal of commitment.”

“Learning a new language takes a great deal of commitment.”

“The most common online learning taking place around the country today takes a great deal of commitment.”4

The second example, the first to demonstrate a complex subject is fine enough, but the third example is eleven words long, and the sentence still isn’t moving. This is what makes people think they hate long sentences and why so much professional writing is impossible to decipher.

Is there something lost in its removal? Yes, the image McCarthy is trying to create is evocative of the type of house we’re entering into. We learn later that the ranch has fallen on hard times, but there’s a history of prosperity here and an attempt at class. That’s irrelevant if readers don’t understand what they’re reading. McCarthy gets away with it. If I try to start a book this way (and I pray to to God I haven’t), the reader wouldn’t bother attempting to pry lose its meaning. Confusion in the first sentence is the kiss of death for an author—unless that author already has our trust. We trust McCarthy, so we work through our confusion and move on.

Where the long sentence seeks to avoid tripping itself up with confusing clauses or phrases, for the paragraph, the importance is placed upon the whole sentence as well. In this first paragraph, we find a pattern to the sentences, none of them repeating the mistake of confusing the reader:

1 long sentence-2 short sentences-2 long setences-2 short sentences-1 long sentences-2 short sentences5

In structure, it feels like poem, even ending with the coda: This was not sleeping. This was not sleeping.

(continued below)

New Subscribers and Transfers from my Author Site

For reasons intentional (not wanting to subscribe transfers to material unlike what you signed up for) and unintentional (the whole transfer process has been confusing): YOU MAY NOT BE SUBSCRIBED TO EVERYTHING YOU WANT FROM ME.

Toggle your choices at https://literarysalon.thaddeusthomas.com/account

And see what other essays I have to offer here:

And don’t forget my short fiction and serials.

This is not an argument for the dumbing down of literature.

There’s a sentence from later in the book that was highlighted by an English teacher trying to puzzle out its grammar:

Leading the horses by hand out through the gate into the road and mounting up and riding the horses side by side up the ciénaga road with the moon in the west and some dogs barking over toward the shearingsheds and the greyhounds answering back from their pens and him closing the gate and turning and holding his cupped hands for her to step into and lifting her onto the black horse's naked back and then untying the stallion from the gate and stepping once onto the gateslat and mounting up all in one motion and turning the horse and them riding side by side up the ciénaga road with the moon in the west like a moon of white linen hung from the wires and some dogs barking.

There’s nothing to puzzle out here. Normal grammar isn’t used but rather the same mentality as when I text my wife: kissing you.

The sentence has neither subject nor verb but is entirely made up of verb phrases, like a cumulative sentence with its head cut off. That’s a long sentence that lacks proper grammar—but the reader can follow its movement. In a The Secret of Style: Part II, which also builds off of this study of All the Pretty Horses, I talk about how McCarthy’s polysyndeton slows the action down, but I’d argue this run of verb phrases has the opposite effect. It’s a cascade of moments washing over him in the presence of the woman he loves.

The rules matter only as far as they improve communication, and it’s not even a grammatical rule to avoid cumbersome complex subjects. It’s a matter of better communication through style.

—Thaddeus Thomas

Looking for more fiction writers on Substack? I’ve started a list of recommendations:

End Notes

There is always an exception to any rule. I argure this isn’t it.

Long is a relative term.

I dislike writing rules. Like cattle chutes, they funnel most writers into the same pen. So often, published stories read about the same. Language gives us many opportunities to create not only engaging plots but also stories that appeal to our senses and expand our awareness. McCarthy is brilliant in the way he weaves words into a sensory tapestry.

I'm not sure I was aware of any unspoken rule against compound subjects as regards good style (or is it only complex compound subjects with unilateral modifiers prior to the verb?). I am however constantly intuiting whether a sentence's construction is impairing its clarity; consciously considering complex compound subjects would be a good criterion for identifying hang-ups in my sentences.

That said, the opening sentence to ATPH's never really tripped me up. But my dumb reptile brain got stuck on the second sentence of Cold Mountain once because it wouldn't stop reading the word "wound" as the past tense of "wind..." the verb not the noun. Very puzzling reading experience until I got that sorted haha