DOGE and the Coming Tsunami

Elon Musk is aggressively and foolishly courting catastrophic risk. We'd be wise to learn from the wisdom of the Moken people to stave off disaster—before it's too late.

Thank you for reading The Garden of Forking Paths. Some of this edition is for paid subscribers only, so to unlock this post and gain full access to 180+ other essays from the archive, consider upgrading to a paid subscription for just $4/month. I rely exclusively on reader support to keep writing for you. Or, you could also check out my book—FLUKE.

I: The Coming Laboon

On December 26, 2004, at 7:58 in the morning, the thick plates beneath Sumatra’s west coast began to shake violently. For ten terrifying minutes, the earth split apart, forming a rupture that stretched for more than 700 miles. The earthquake, which was the third most powerful ever recorded, caused the entire planet to vibrate.

But its true destruction was yet to come, as water was swept away from the epicenter, a gargantuan surge sloshing toward unsuspecting people on distant coastlines, at the speed of a jet airplane. A quarter of a million of those people—228,000 souls in total—would be dead within hours, marking the Boxing Day tsunami as the worst natural disaster of the 21st century. (So far).

On the Surin Islands off the west coast of Thailand—where I’m currently writing to you from—one group of people didn’t die: the Moken.1 This indigenous community, known sometimes as the sea gypsies, is so intertwined with the sea that they “learn to swim before they can walk.”2 Through the generations, collective wisdom about their ocean lifestyle was passed down through ancestor narratives. Among them, there was a cautionary tale warning of a rare peril that lurked within the ocean, the coming of a laboon: a wave that eats people.

As an invisible force mysteriously sucked the water away from pristine beaches, Thai villagers and tourists alike near Khao Lak ventured out to collect stranded sea life. But on the Surin Islands, the reverse surge resurrected the lingering knowledge of their forefathers. They warned nearby boats filled with unaware tourists, then headed inland, saving countless lives—then saving themselves.

By contrast, those in nearby Khao Lak had no warning; up to 8,000 people, tourists and locals alike, were killed by the relentless fury of the sea.

None of the governments in the area had bothered to invest in early warning systems; it was viewed as a wasteful, unnecessary, inefficient expense. After all, year after year had gone by without a tsunami, so what politician would want to champion a major new investment in emergency preparedness? The money would have to be spent now, but the political credit would be taken later—and possibly by a political rival.

Tsunami prevention follows a predictably foolish but instructive pattern. It is only after large numbers of people are killed that governments tend to start pouring money into prevention, which is why the United States only began tackling the problem in 1949, a few years after a tsunami unleashed a 45-foot wave that killed hundreds of people in Hawaii. Following an even more destructive tsunami that struck Chile in 1960, the United States helped to build and host a far more robust early warning system. But it had limited reach.

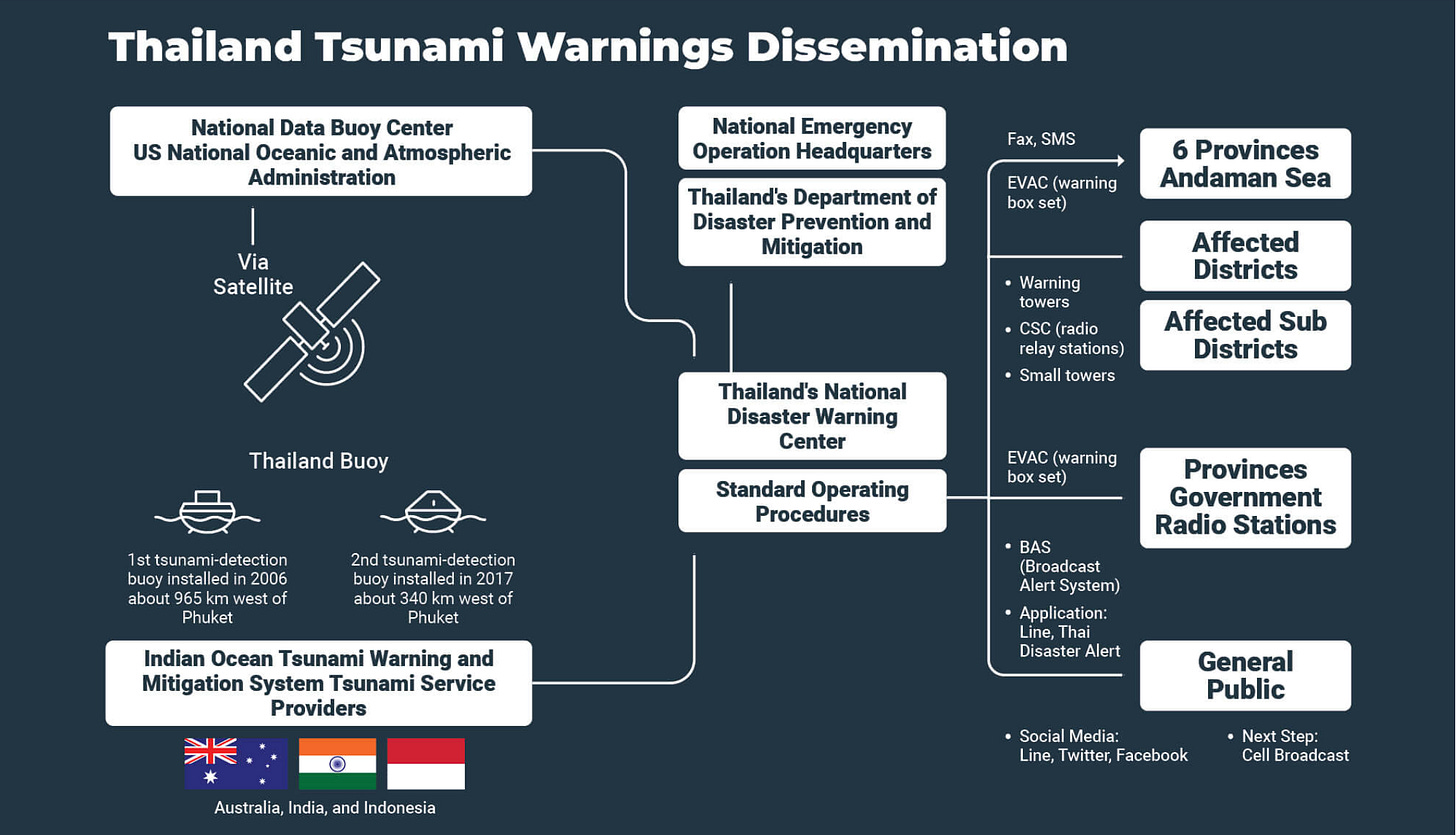

As a result, in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami that caused billions in damage and left hundreds of thousands dead, Asian governments turned to the United States for help—and USAID delivered, providing funding and technical advice to build a new early warning detection system that soon featured 148 seismometers.3 Additionally, Thailand, in coordination with the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has installed advanced warning systems, along with education programs—bringing the wisdom of the Moken to everyone else who lives along the Thai coastline.

Now, almost exactly two decades after the waves struck coastlines here in the Andaman Sea, this tragic saga offers a useful parable for ourselves in 2025.

We inhabit a period of unparalleled existential risk from interlaced crises—social, political, technological, and ecological.

By unravelling the hidden lessons from that destructive tsunami, it will become devastatingly apparent why Elon Musk’s efforts to take a literal chainsaw to the federal government are recklessly inviting tragedy on a potentially cataclysmic scale, beckoning a tsunami-scale disaster that will soon hit American shores.

The parable of the Surin Islands and the mythology of the laboon provide insights to better understand:

Why government “waste” is often just preparedness and resilience;

How seemingly wasteful spending being slashed by DOGE actually saves money through long-term planning;

How risk tolerance and catastrophic risk differs in the public and private sectors (and why Elon Musk treating the US government like Twitter is a disaster waiting to happen); and

Why knowledge production and retention act as bulwarks against risk (and why the ongoing attack on the US knowledge industry is therefore deeply dangerous).

But unlike the laboon, as we will see, the cresting Muskian wave will not just eat people who live in its geographical path, but will rather needlessly flood the entire globe with a surge of avoidable catastrophic risk.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Garden of Forking Paths to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.