I’ve written about federal government arts funding in the past. Back then I highlighted the fact that you can plow billions into programs for producing art, but if no one’s interested in consuming what comes out the other end, then what do you have to show for the exercise?

Why dredge all that up again now? Over on his Substack, publisher and editor Ken Whyte recently quoted at length some related thoughts from industry veteran Patrick Crean. Based on a lot of inside experience, Crean is critical of the way the Canada Council supports the publishing of some "really bad stuff" from as many as 120 English language publishers. In its current form, the system invites box-checking and system-gaming. "Some publishers," Crean wrote, "make more money from the government than they do from sales."

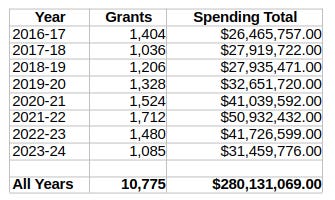

Which got me thinking. Is it possible to actually measure the impact government funding has on the number of people who read Canadian books? Funding totals are easy enough to find. Here’s how much the Canada Council for the Arts spent over the past eight years on books that fall in the category they identify as literature:

And Treasury Board numbers for 2024-45 report $34,000,000 in grants, and $2,666,301 in contributions for the Canada Book Fund. We can therefore estimate that, between the Canada Council and the Canada Book Fund, more than a half billion dollars was spent on book production over the past eight years.

So what did Canadians get for their money? Ideally, I’d prefer to measure that using a hard metric like book sales. In other words, how many more books are Canadian publishers able to sell each year due to the government grants they receive. But that kind of detailed data is hard to find.

Statistics Canada does measure financial revenues for Canadian book publishers, but it lumps all “trade book” sales together. When you consider how big sellers like Margaret Atwood, Michael Ondaatje, Cherie Dimaline, and Desmond Cole dominate the trade market, it’s obvious that a single yearly sales figure isn’t going to tell you anything about grant recipients struggling for attention.

So, for want of anything better, I decided to generate my own statistics. My ever-loyal AI research assistant gave me the titles of 40 books published in the last two years by 20 Canadian publishers receiving federal grants. These books stretch across multiple genres, including fiction, memoir, poetry, young adult, and non-fiction. They also include a wide range of publishers1. And a couple of the authors were so famous even I’d heard of them.

I then collected the Amazon Best Sellers Rank for the softcover edition of the books on the list on Amazon.ca. The Best Sellers Rank (BSR) is far from a perfect measure of success, but it is possible to use it to broadly estimate the number of copies a book is selling each month.

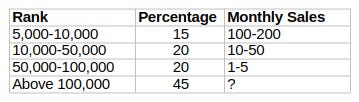

Here are the estimated monthly sales for the four categories of books from that list:

In other words, only 15 percent of the books I looked at were likely to sell anywhere close to 1,000 copies in a year. Of course, those numbers only represent softcover sales on Amazon. I’d double that to account for Amazon sales in all formats, and double that amount to incorporate non-Amazon sales.

Which is to say that I think we can assume that only the top 35 percent of those books can reasonably expect to sell more than 500 copies in each of their first couple of years. The other 65 percent will sadly leave this cruel world much the way they found it.

Of course, what we’ll never know is how many of those books would have been written, printed, sold, and read had the Canada Book Fund and Canada Council for the Arts never existed. Nor is there any easy way to measure the positive social benefits the books that are published leave behind. So accurately measuring the full impact of these programs isn’t possible.

But I’m not convinced that the people who make funding decisions have all that much better information at their disposal than I do. And if the government’s goal is to help Canadians find high-quality home-grown literature, do the actual results justify a half billion dollars in public spending?

An earlier version of this post implied that the giant Canadian publisher McClelland & Stewart received grants. This is incorrect.

The answer to the question you pose at the end of your article is no. An inefficient, ineffective method of disposing of tax payer funds that may or may not be heavily influenced by ideology. What you’ve shown here is another example of government waste which could be eliminated by a government intent upon reducing expenditures and showing some respect for the tax dollars it extracts from hard working citizens.

Grants should reward success, not failure.

More books sold then the bigger the grant.