The one constant through all my years has been baseball.

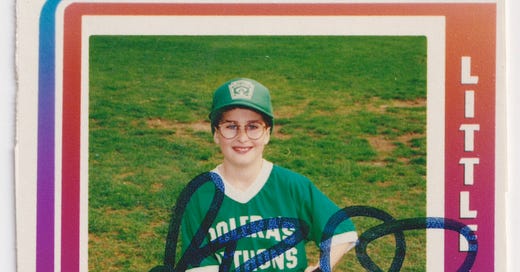

I’ve been swinging bats since I was in short pants, leveling up from tee-ball to D-III ball as an all-glove/no-hit, all-love/no-quit corner infielder. To this day you can still catch me stirruped and cleated on the odd weekend ramble, punching seeing-eye singles and flashing mild-to-moderate leather with a middle-aged menagerie of fellow diamond die-hards.

But baseball has always been more than a pastime for me; more than merely a sport to be spectated from the bleachers or participated in between the chalk lines. As the oversized t-shirt I regularly wore throughout my late elementary and middle school years loudly stated in bold serif font: Baseball Is Life (the rest —piano lessons, Bar Mitzvah prep, the geopolitical implications of Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule — were just details).

I collected baseball cards, poring over the capsule biographies and lifetime statistics of the often stiffly posed subjects on the obverse, carefully and inscrutably arranging them in nine-pocket, plastic-sleeved protective pages that filled binder after binder.

I devoured baseball news and analysis with subscriptions to specialty publications like Baseball America, Baseball Weekly, and Baseball Digest supplementing the more catholic coverage of Sports Illustrated and The Sporting News, and I embarked on an independent study of baseball history that began with the excavation of my dad’s old cards from the ‘50s and ‘60s and culminated with my becoming the youngest member of the Society of American Baseball Research’s Casey Stengel Chapter.

Even in the face of a burgeoning pubescence that countered vigorous incursions of horniness at every turn and from every imaginable source, the compilation and consumption of all things horsehide is where I steadfastly devoted the vast majority of my mental energy.1

In short, I was one cool fucking kid.

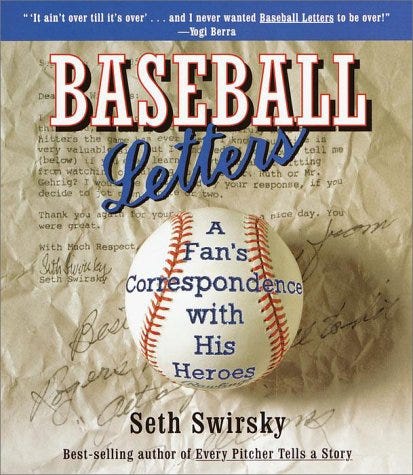

In the course of my scholarly survey of available baseball literature, I came across a bluntly titled book by a memorably alliterative man: Baseball Letters by Seth Swirsky. The story goes that Seth, a baseball fan bereft of baseball to watch in the strike-shortened 1994 season, began writing letters to hundreds of players, past and present, proffering questions about their lives and careers. Many of them wrote back, and those correspondences became the basis for his book.

Instantly hooked by the simple premise and the author’s oddly similar name to my own, I was inspired to take up the very same endeavor. Armed with Jack Smalling’s Baseball Autograph Collector’s Handbook — a slim but mighty volume which magically listed the mailing addresses of every living former Major Leaguer — and undistracted by even the faintest idea of finding a girlfriend, I opened Microsoft Word on my Bondi Blue iMac G3 and typed out my first letter.

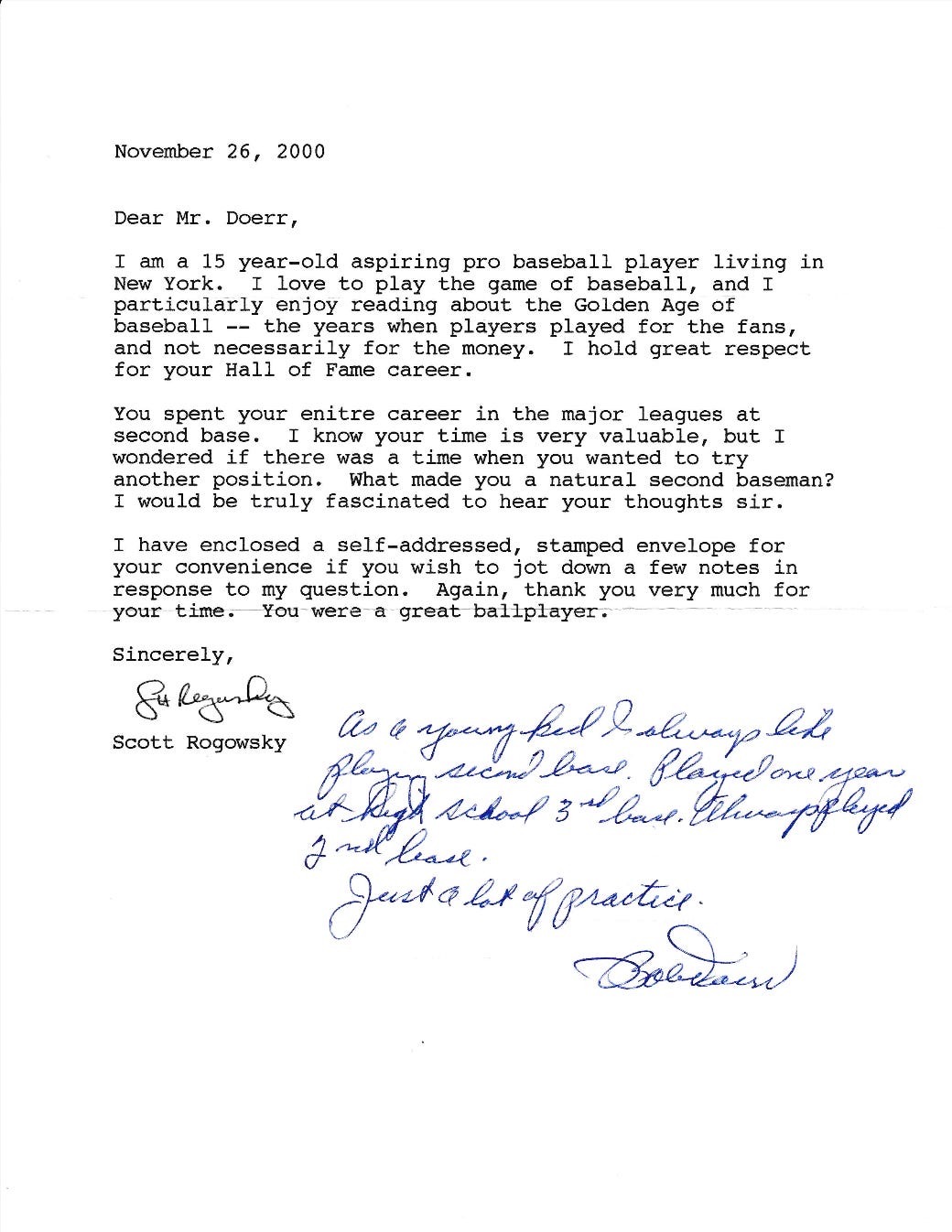

By dint of Boston shortstop Nomar Garciaparra being my favorite active player at the time, I had gone particularly deep down the rabbit hole of Red Sox lore, to the point where there could be only one logical recipient of my maiden missive: Bobby Doerr. Name another Y2K teenager who spent his sophomore Thanksgiving break writing to an 82-year-old Hall of Fame second baseman — I’LL WAIT.

As a young kid I always liked playing second base. Played one year at high school 3rd base. Always played 2nd base. Just a lot of practice. Bobby wrote me back on the same piece of 20 lb. weight printer paper I sent him, replying to my simple question with a simple answer in handwritten script he must have learned as a grade schooler during the Calvin Coolidge administration, and returning it with the self-addressed stamped envelope essential to any successful through-the-mail attempt.

Emboldened, I kept writing… and writing… on and off, for years and years… targeting the oldest living extant ballplayers in hopes I would reach them before they reached their expiration dates. Realizing beginner’s luck might have been a factor in Bobby Doerr’s case, I homed in on the lesser-known and outright unknown names of the Baseball Almanac who nonetheless had brushes with greatness in the form of teammates, opponents, or managers and coaches.

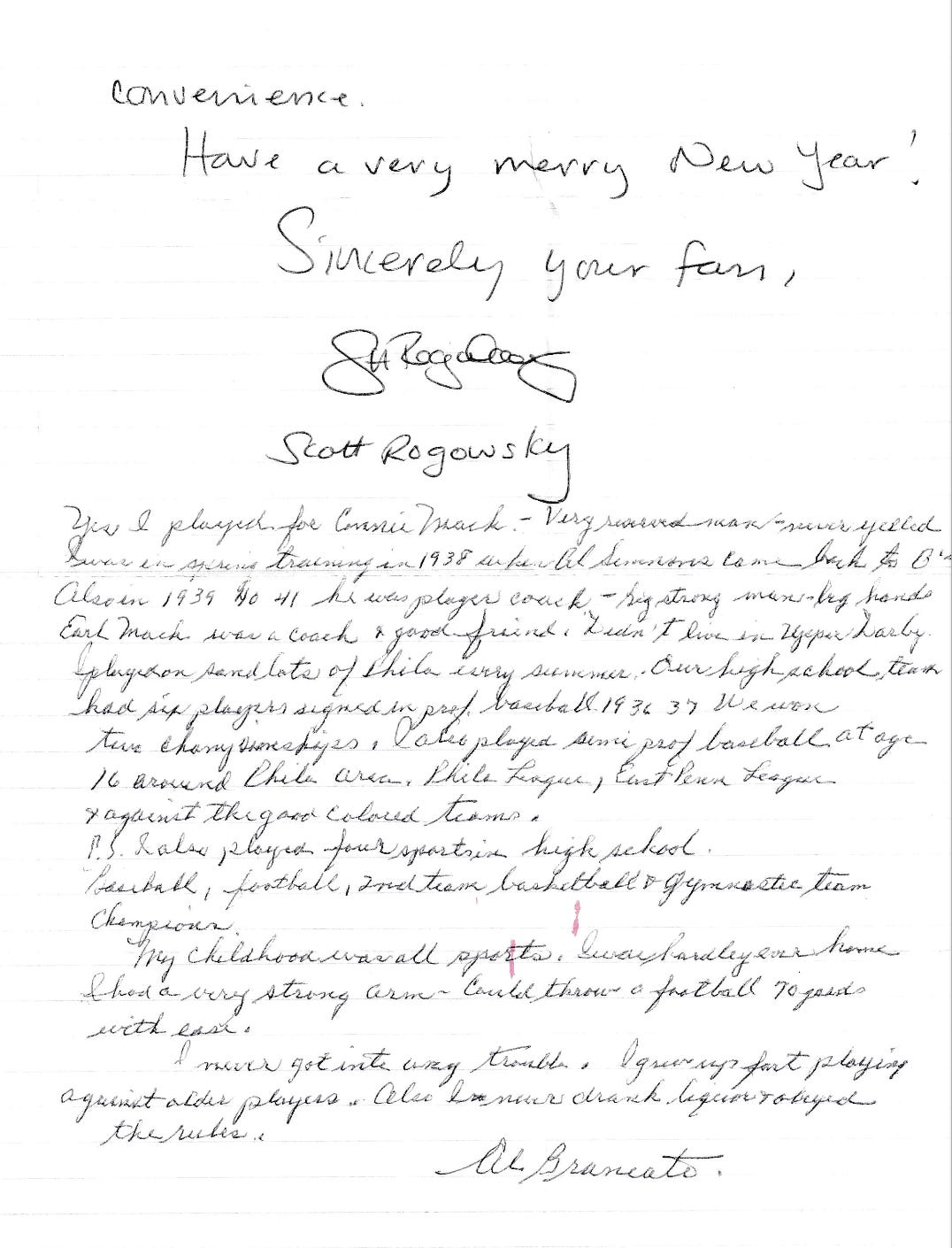

Al Brancato was one such individual, a light-hitting, poor-fielding shortstop/third baseman who got into 272 games across three pre-war seasons with the Connie Mack-helmed and Al Simmons-coached Philadelphia Athletics.2 I asked Mr. Brancato for his memories of playing amidst these legendary baseball figures:

Yes I played for Connie Mack. Very reserved man - never yelled. I was in Spring Training in 1938 when Al Simmons came back to A's. Also in 1939-40-41 he was player/coach. Big strong man, big hands. Earl [sic] Mack was a coach & good friend. Didn't live in Upper Darby. I played on sand lots of Phila every summer. Our high school team had six players signed in prof baseball. 1936-37 we won two championships. I also played semi prof baseball at age 16 around Phila area. Phila League, East Penn League & against the good colored teams.

P.S. I also played four sports in high school. Baseball, football, 2nd team basketball & gymnastics team champions.

My childhood was all sports. I was hardly ever home. I had a very strong arm - could throw a football 70 yards with ease.

I never got into any trouble. I grew up fast playing against older players. Also I never drank liquor & obeyed the rules. Arriving home from school soon and running to the mailbox became the most thrilling part of my day, sodden as it was with anticipation for what typographical treasures may have been mixed among the utility bills and pennysavers. And the surprise would be manifold: Did anything come? Who is it from? What did they say? Many players were gracious enough to send multipage, handwritten responses and include extras like photocopied articles or unsolicited autographed cards and photos. Others scribbled out a few words on my original letter and didn’t even bother to sign off. Some I never heard back from at all.

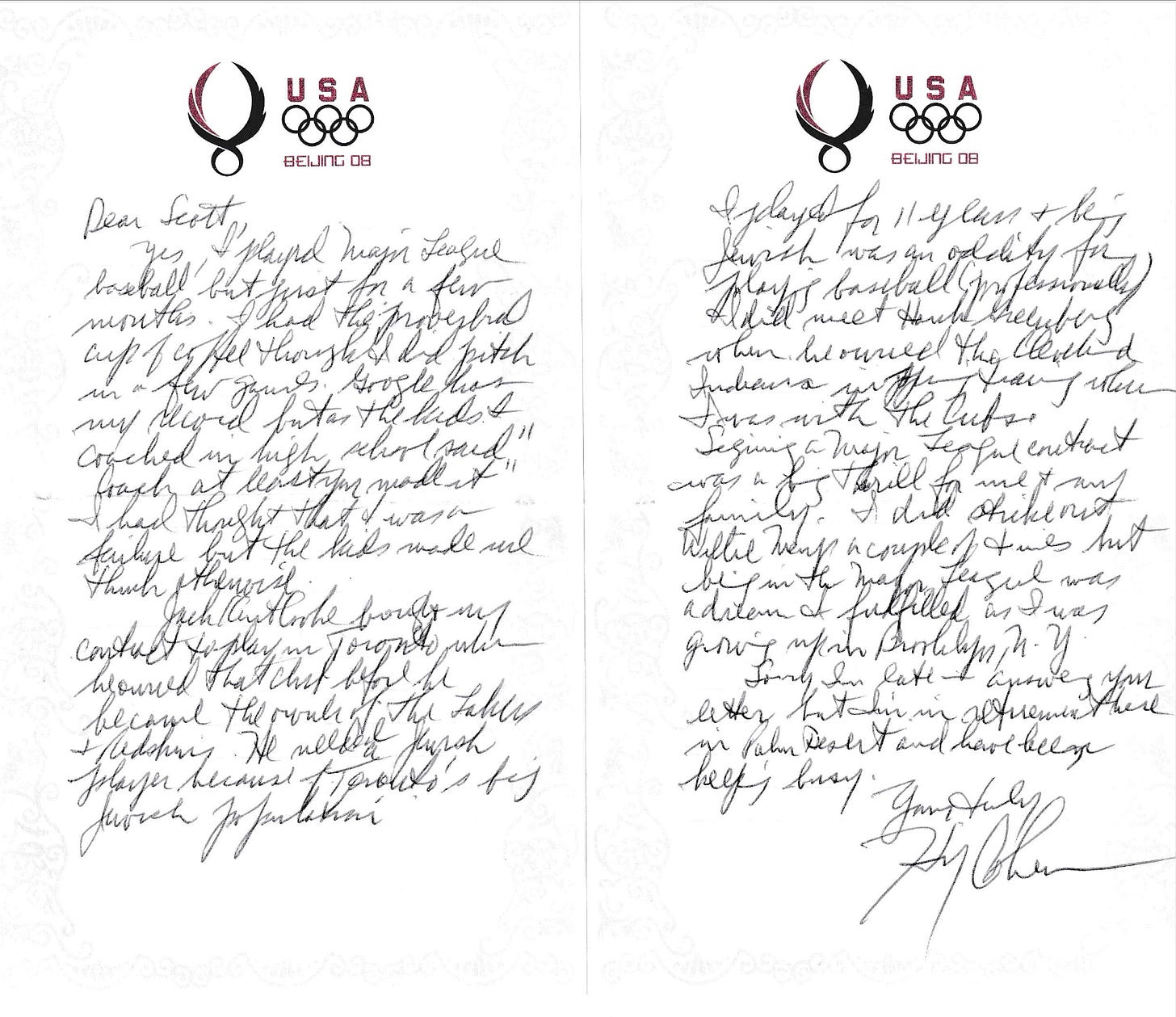

Dear Scott, Yes I played Major League baseball but Just for a few months. I had the proverbial cup of coffee though I did pitch in a few games. Google has my record but as the kids I coached in high school said, "Coach at least you made it." I had thought I was a failure but the kids made me think otherwise.

Jack Kent Cooke bought my contract to play in Toronto when he owned that club before he became the owner of the Lakers & Redskins. He needed a Jewish player because of Toronto's big Jewish population.

I played for 11 years & being Jewish was an oddity for playing baseball (professionally). I did meet Hank Greenberg when he owned the Cleveland Indians in Spring Training when I was with the Cubs.

Signing a Major League contract was a big thrill for me & my family. I did strike out Willie Mays a couple of times but being in the Major Leagues was a dream I fulfilled as I was growing up in Brooklyn, NY.

Sorry I'm late in answering your letter but I'm in retirement here in Palm Desert and have been keeping busy.

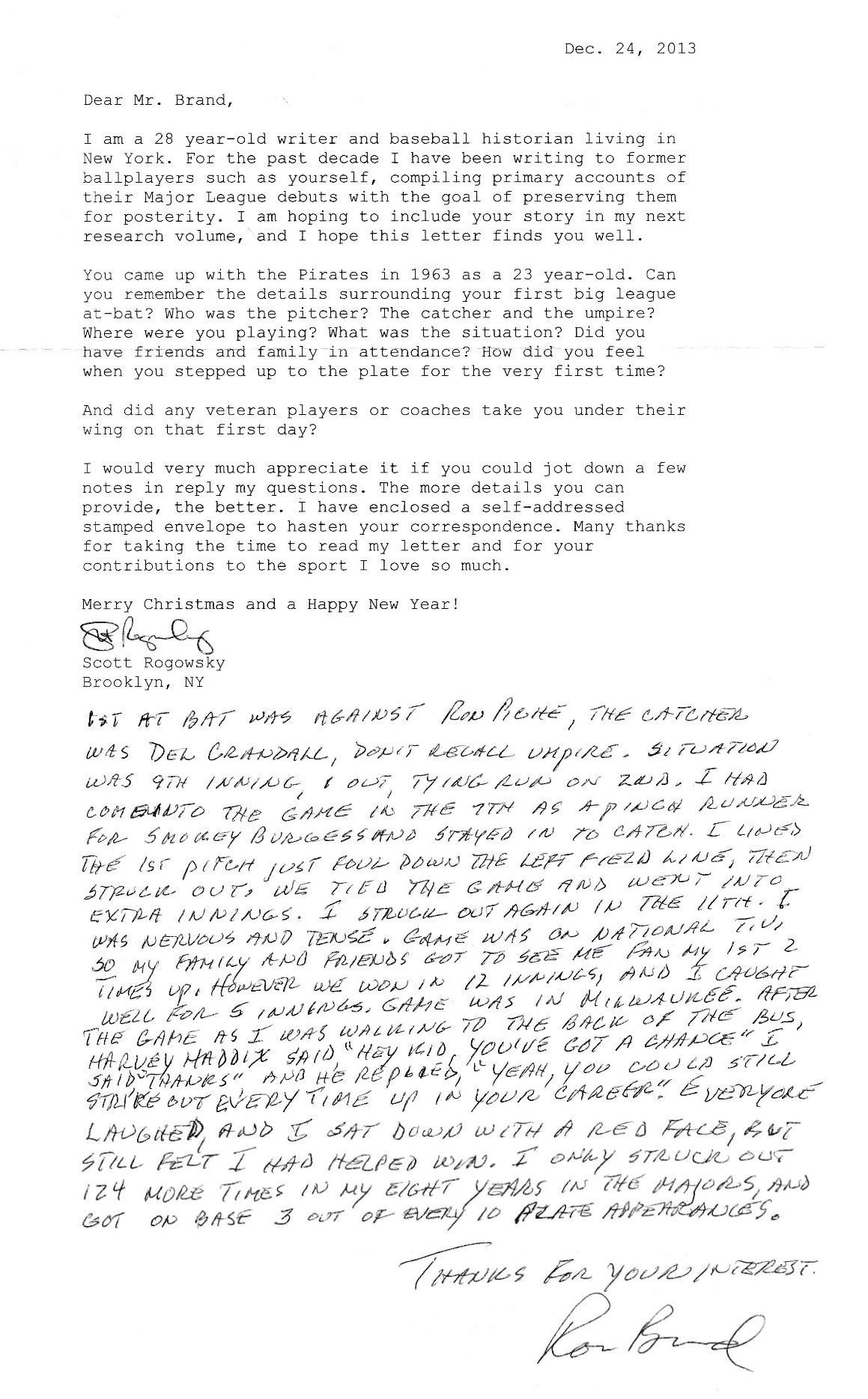

As my letter writing evolved, I focused my line of questioning and hit upon the concept of gathering stories about a player’s first Major League appearance, either in the batter’s box as a hitter or on the rubber as a pitcher, with the goal of compiling them into a Baseball Letters-esque book of my own. I asked these old-timers if they could recall the circumstances of their first at-bat or first pitch: Where was the game? What was the situation when they entered? Who did they face? What was the result? Were friends or family in the stands to watch? How did they feel in that moment?

A sustained campaign over 2013-14 netted hundreds of such stories, scrawled in varying degrees of specificity and legibility. Being as it were that nearly all of my Golden Age addressees were in their golden years when I made contact, invariably some players were unable to recall such details from five or six decades prior.

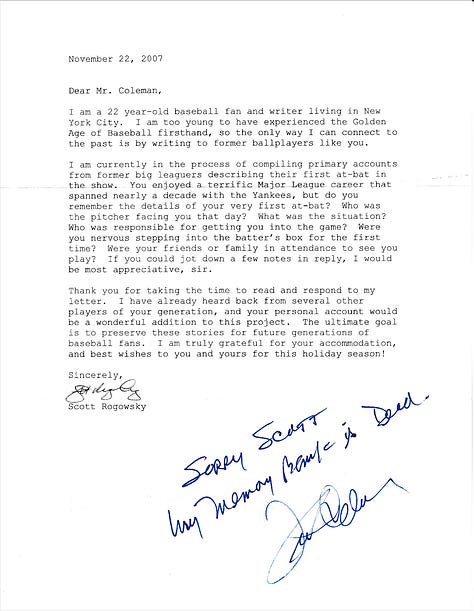

Sorry Scott, My Memory Bank is Dead. - Jerry Coleman

-----

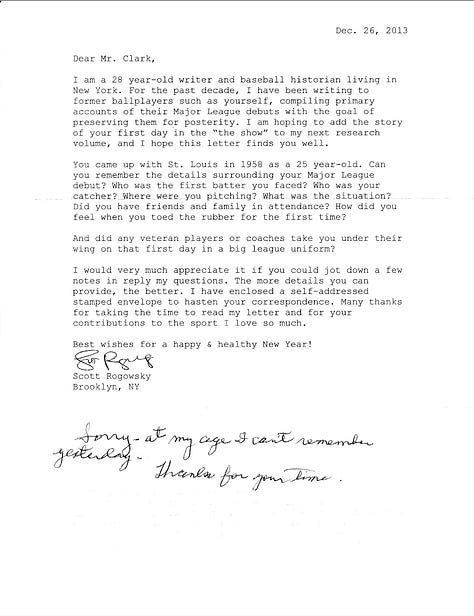

Sorry, at my age I can't remember yesterday. Thanks for your time. (Phil Clark)

-----

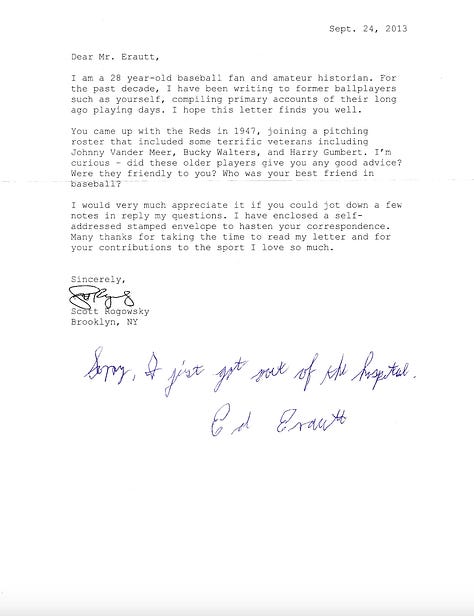

Sorry, I just got out of the hospital. - Ed ErauttA few times a note would come back in the hand of player’s relative or caretaker informing me of an incapacitation that had befallen my intended mark.

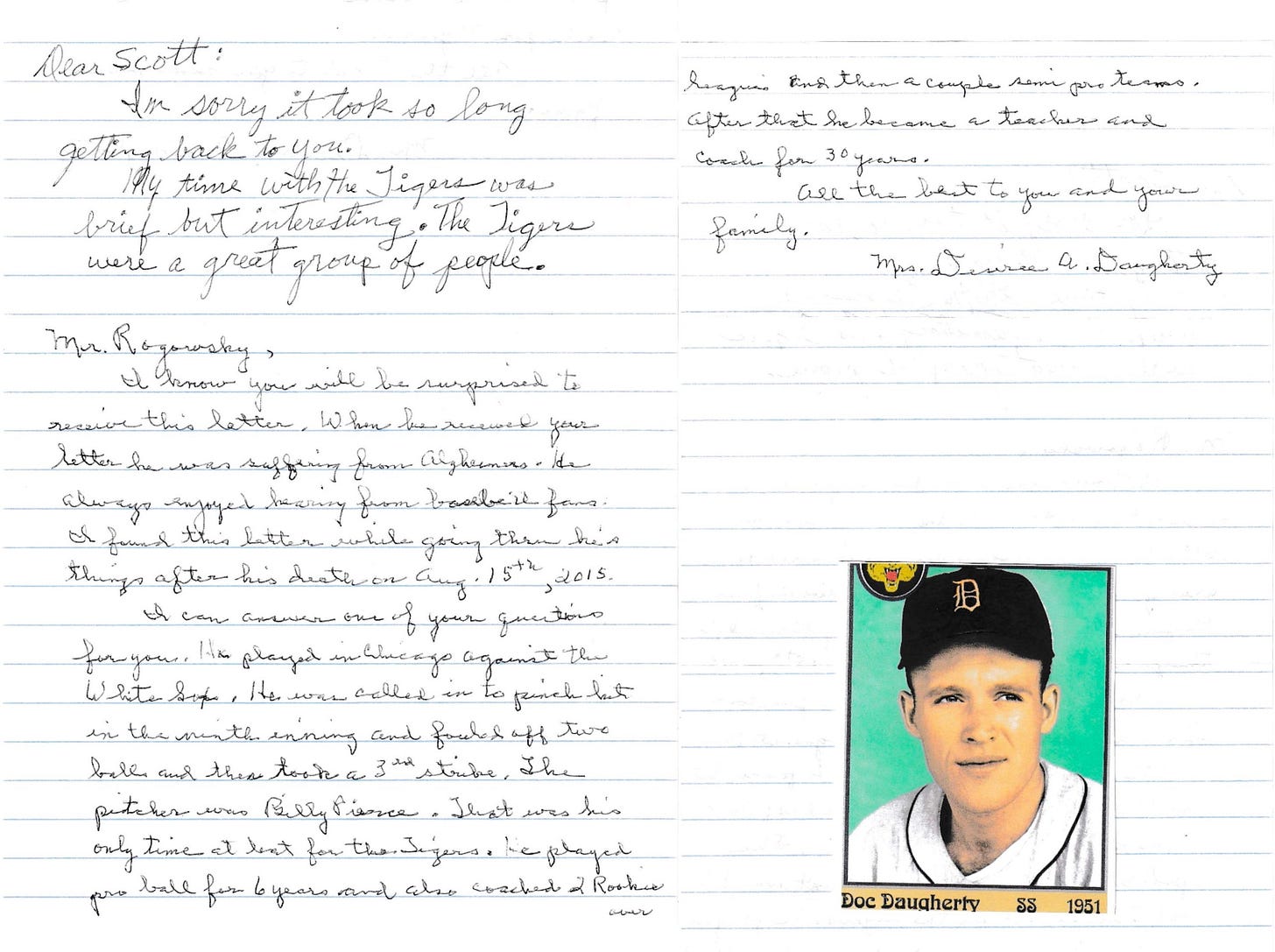

Dear Scott: I’m sorry it took so long getting back to you. My time with the Tigers was brief but interesting. The Tigers were a great group of people.

-----

Mr. Rogowsky, I know you will be surprised to receive this letter. When he received your letter he was suffering from Alzheimer's. He always enjoyed hearing from baseball fans. I found this letter while going through his things after his death on Aug. 15, 2015.

I can answer one of your questions for you. He played in Chicago against the White Sox. He was called in to pinch hit in the ninth inning and fouled off two balls and then took a 3rd strike. The pitcher was Billy Pierce. That was his only time at bat for the Tigers. He played pro ball for 6 years and also coached 2 Rookie Leagues and then a couple semi pro teams. After that he became a teacher and a coach for 30 years.

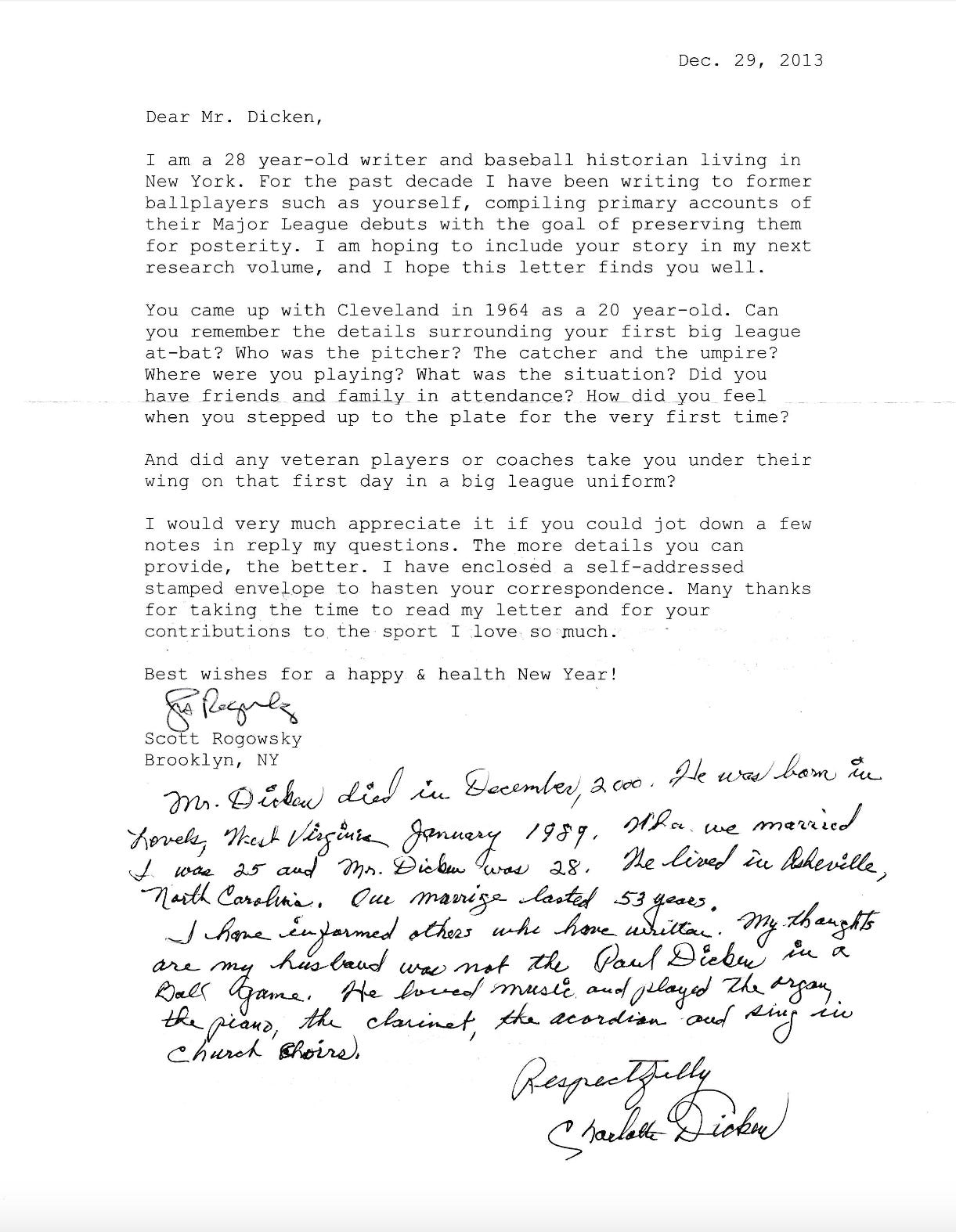

All the best to you and your family, Mrs. Desiree A. DaughteryThe most delightfully bizarre reply I ever received was from the extremely proud and patient widow of a man whose identity had been confused with that of a 1960s Cleveland Indians player of the same name, and whose address had been mistakenly included in the autograph collector’s handbook.

Mr. Dicken died in December, 2000. He was born in Levels, West Virginia January 1919. When we married I was 25 and Mr. Dicken was 28. We lived in Asheville, North Carolina. Our marriage lasted 53 years.

I have informed others who have written. My thoughts are my husband was not the Paul Dicken in a Ball game. He loved music and played the organ, the piano, the clarinet, the accordion and sing [sic] in church choirs.

Respectfully, Charlotte DickenBut plenty fit the bill for my hypothetical book. The only problem was… I had no clue how to put a book together to begin with, no connections to the literary world once I had a manuscript in place, and no clue if any publisher would be interested in buying the finished product once I devised it. Had Seth Swirsky already cornered whatever niche market there may have been?

Alas, over a decade has passed since wrestling with this project’s existential crisis (one in a lifelong series of crises), and in that time my letters have remained sleeved and UV-protected in alphabetically-ordered binders (see footnote No. 1). But I’m revisiting them today, and finally publishing them independently on this here ‘stack, in celebration of the start of yet another Major League Baseball season, and with deep gratitude and appreciation for the players — many now deceased — who respected the inquiries of an “amateur baseball historian.”

I can’t possibly publish them all in this instant, but I plan to update this page over the season with new additions, so perhaps add to your bookmarks and revisit at your pleasure. Until then… PLAY BALL!

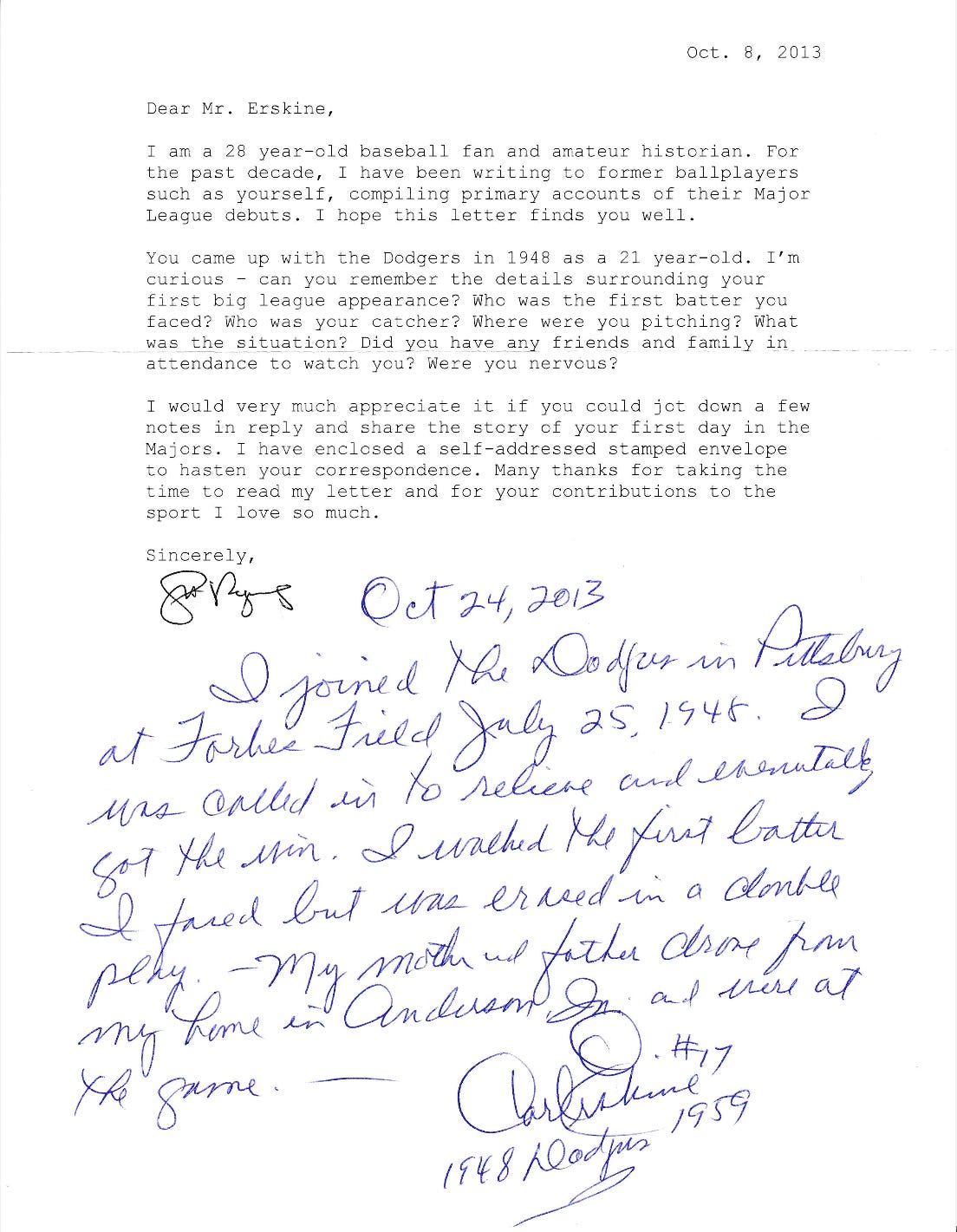

I joined the Dodgers in Pittsburg [sic] at Forbes Field July 25, 1948. I was called in to relieve and eventually got the win. I walked the first batter I faced but was erased in a double play. My mother and father drove from my home in Anderson, IN and were at the game.

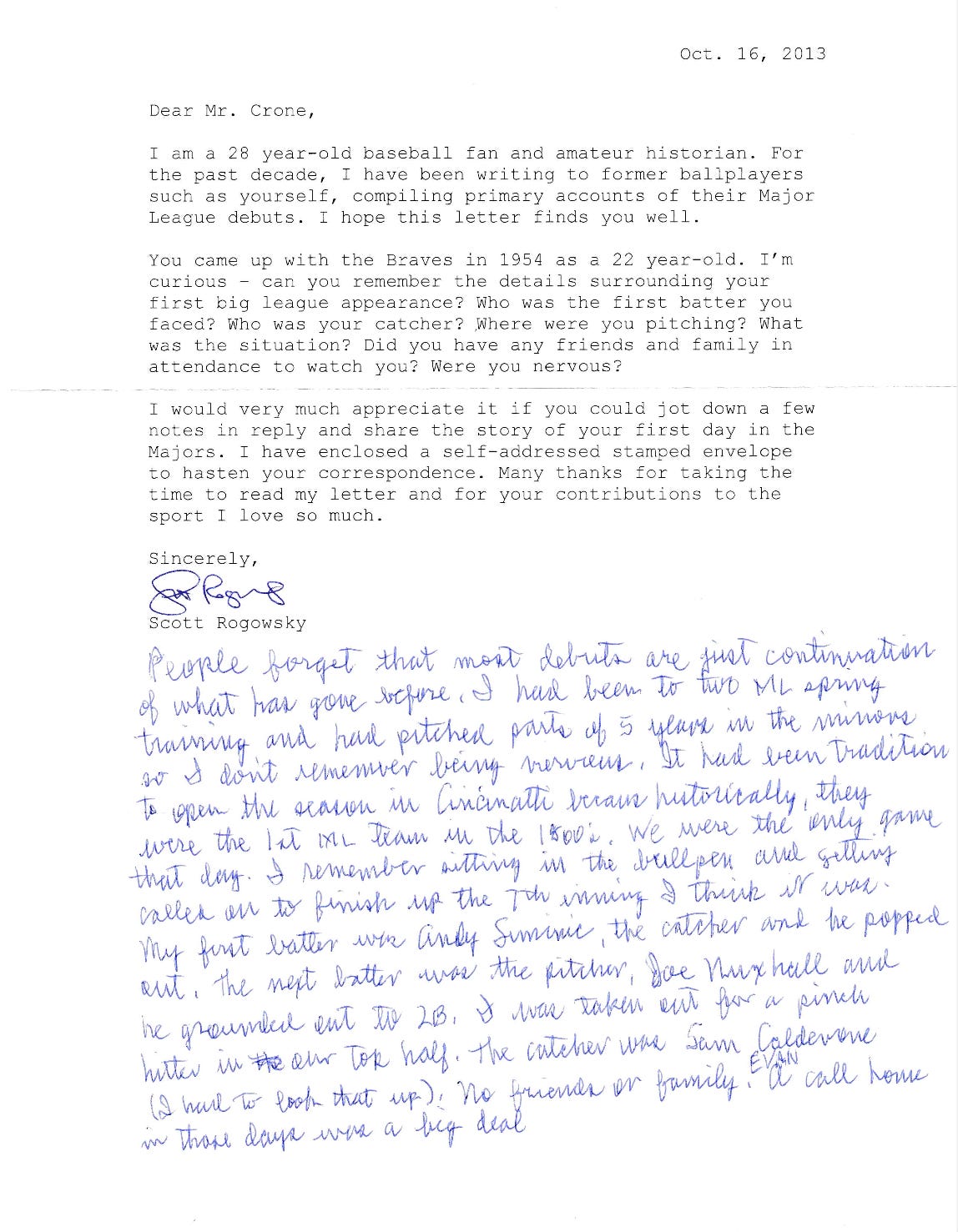

People forget that most debuts are just continuation of what has gone before. I had been to two ML spring training and had pitched parts of 5 years in the minors so I don't remember being nervous. It had been tradition to open the season in Cincinnati because historically they were the 1st ML team in the 1800's. We were the only game that day. I remember sitting in the bullpen and getting called on to finish up the 7th inning I think it was. My first batter was Andy Seminick, the catcher and he popped out. The next batter was the pitcher, Joe Nuxhall and he grounded out to 2B. I was taken out for a pinch hitter in our top half. The catcher was Sam Calderone (I had to look that up). No friends or family. Even a call home in those days was a big deal.

With the help of modern psychiatry, I would much later come to understand the source of this “energy” as a latent obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Cornelius McGillicuddy aka Connie Mack remains MLB’s all-time winningest skipper. Hall of Fame outfielder Al Simmons is unanimously considered to be among the top 100 greatest players of the 20th century.