How low is Trump's popularity floor?

So far, the decline in his approval ratings is typical for new presidents. But second-term presidents can have more downside.

It’s been a busy week: I’ve been in the midst of moving apartments1 and we have a lot of new subscribers because of the NCAA Tournament. But don’t worry, we haven’t forgotten about politics, which is why you’re getting a relatively unusual Saturday brunchtime politics newsletter.

The next edition of our monthly subscriber questions series is also coming up soon: paid subscribers can ask questions in the comments of last month’s thread.

A fellow Substacker messaged me the other day to ask why President Trump’s approval rating had been so resilient despite problems in the economy and elsewhere. I argued that it hadn’t been, really. In our approval rating tracker, Trump started out at a +11.6 net approval rating, a much better opening number than in his first term. But now, he’s in the red at -2.2. So there’s actually been a fair amount of movement:

From the first full day of his presidency, Jan. 21, through yesterday — March 21: conveniently exactly two months later — Trump’s net approval rating has declined by 13.8 points, so around 7 points per month. A president can’t afford that rate of decline for long. Extrapolate out the trend, for instance, and Trump would be at a -27.6 by July 21, a -51.2 on Nov. 21, and so forth.

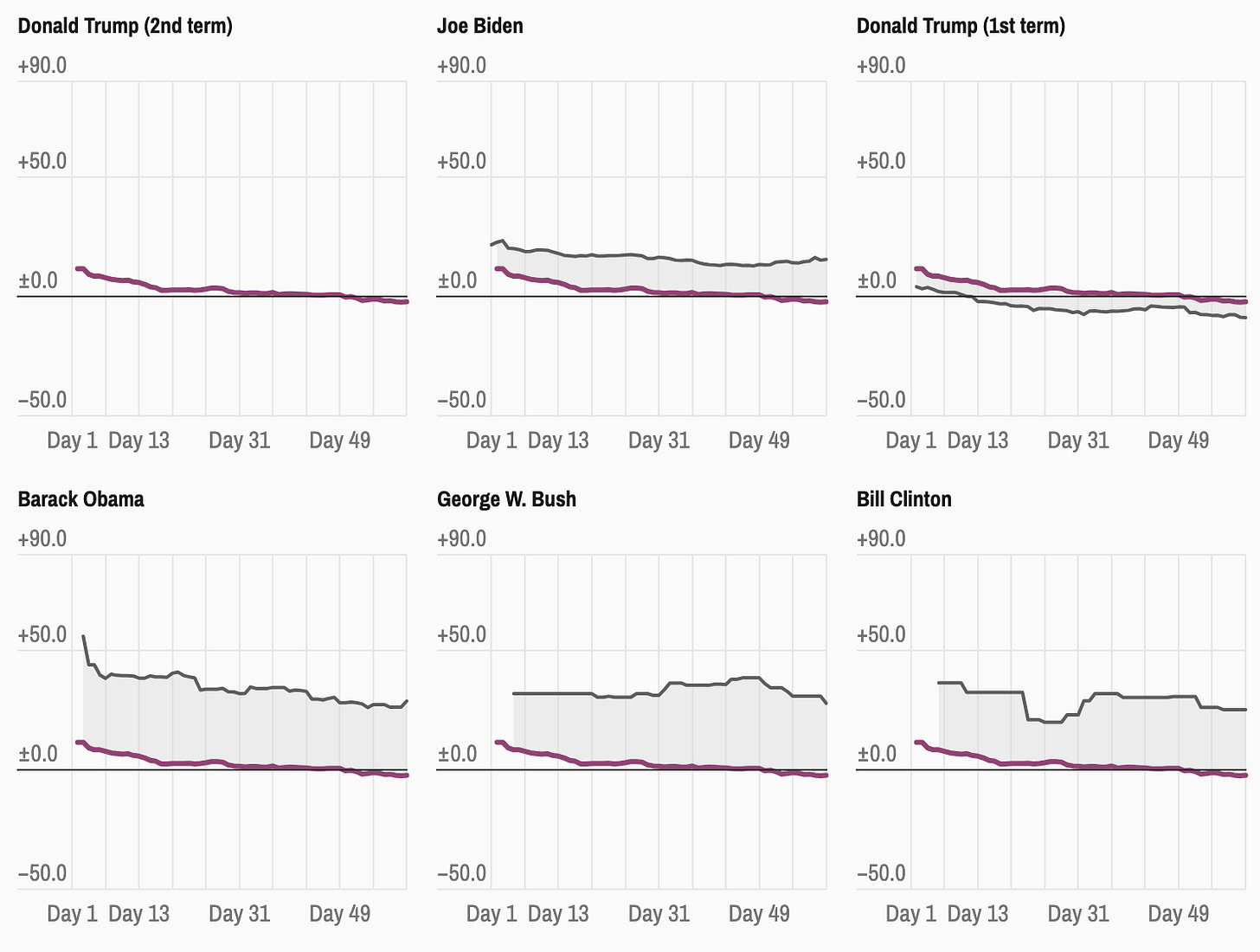

Fortunately for Trump, that’s not how any of this works — and such crude linear extrapolation will almost certainly lead to bad predictions. There are two reasons for this. First, the decline he’s experienced is quite typical for new presidents. Let’s start the clock on Feb. 1 rather than Jan. 21, though, since approval rating polling is often sparse very early in a president’s term. Here’s how the past five presidents before Trump — including Trump himself in his first term — saw their numbers trend between Feb. 1 and March 21 during their first year in office.2

Or if you prefer a visual — this is the change in Trump’s net approval ratings through 60 days compared to recent past presidents:

If you squint, you might say that Trump’s decline is a bit worse than average — but really only a bit. A president’s disapproval rating typically increases early on, partly because some voters who were initially on the fence and say they were undecided, perhaps out of a sense of hopefulness for a new president, instead begin to tell pollsters they disapprove of his performance. That’s been true for Trump 2.0, as it has been for all recent presidents.

Sometimes, a president’s approval rating is relatively unaffected, however: his disapprovers come out of the woodwork, but his supporters stay with him. In this case, however, Trump has also lost some support among voters who supported him earlier on: his approval rating has declined by a couple of points. Considering he only won the election by 1.7 points in the tipping-point state, Pennsylvania, it’s at least plausible that he wouldn’t win a rematch against Kamala Harris today — although that’s holding Harris’s numbers constant when instead Democrats' numbers have also cratered. Voters are in a grumpy mood toward everybody in politics these days.3

Also, there’s reason to think Trump has a relatively high approval floor. The country is highly divided, and Trump’s supporters are passionate, even if they now constitute a slight minority of the country. In our historical approval numbers, Trump’s first term featured among the lower average approval ratings (41.7 percent, based on the final number at the end of each day of his term) but also the narrowest spread of any presidential term since the dawn of approval ratings. Judged by the 95th percentile range of his daily numbers4, Trump’s approval numbers had a floor of 37.8 but a ceiling of 45.0 during his first term. It fluctuated, but not by much. And now Trump is even more of a known commodity: he’s been the dominant figure in American politics for almost a decade now.

The bad news for Trump, though, is that lame duck presidents typically have both a lower average and a lower floor. In their first terms, the average president since Truman who went on to serve a second term5 had an average approval rating of 58.0 and a floor of 47.1. In these presidents’ respective second terms, however, the average was 48.0 and the floor was 37.7. In particular, Johnson, Nixon and George W. Bush saw their numbers crater in their second term after their re-election (by landslide margins in the case of Johnson and Nixon). I’ve argued before that Bush is an ominous precedent for Trump and a hopeful one for Democrats. In the second (lame duck) term, even partisans might not prop up a president if they think it might be to their advantage to throw him under the bus instead.6

Where Trump might be vulnerable

If Trump’s numbers get worse, it by definition means that some groups of voters turn on him. So which groups might those be? One theory is Last In, First Out (LIFO): that the most recent converts to Trump will be among the first to abandon him. Roughly three groups come to mind here:

Young voters. Trump actually won young voters overall in 2024 in some cuts of the data. (Keep in mind that there’s no hard-and-fast way to know: all methods for breaking down election results by demographic groups rely on statistical extrapolation or polling.) In other data sources, Harris did — though by much narrower margins than Democrats typically attain, and she probably lost young men even if she won among young women. But young voters are less partisan than older ones, and notoriously fickle and influenced by social media trends. And keep in mind that an 18-year-old who voted for Trump last year was just 10 years old at the start of Trump’s first term. It wouldn’t be the first time that teenagers initially support a trendy product to piss off their parents but then get a sense of buyer’s remorse.

Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans and Black men. These groups also shifted heavily toward Trump, though there’s some debate about the magnitude of the change among Black voters. (It’s pretty clear that Black men have increasingly supported Trump, but polls differ on whether Harris gained or lost ground among Black women as compared to Biden in 2020.7) In my predictions column just after the inauguration, I basically operated on the assumption that the recent trend toward racial depolarization — increasingly, Democrats are holding their own among white voters while losing ground among minorities, meaning that the racial gap is narrowing — might actually be a robust one. Black and Hispanic voters are sometimes described as having had “loyalty” to Democrats: I’m not sure I love that framing, but once loyalty is gone, it can be hard to get back. Moreover, most of the shift has been among younger Black, Hispanic and Asian American voters, for whom the Civil Rights Era is now at least two generations removed. But, we’ll see: there’s something to the LIFO theory, too.

Riverian types. What in the heck do I mean by this term? It comes from my book, and it loosely refers to Silicon Valley and Wall Street, but more broadly to a community (“the River”) of quantitative types who are competitive and risk-tolerant. And generally also highly successful financially; these are elites, part of the literal 1 percent. Because of that, they have only a trivial direct influence on election results (especially since many of them live in New York or California) and approval rating numbers. But they can influence them indirectly through their financial leverage and their media presence. I’ve argued recently that there’s some reason to expect a shift among this group, especially Wall Street types who didn’t take Trump’s tariff threats seriously enough. Within Silicon Valley, meanwhile, there’s a lot of groupthink, even if Silicon Valley thinks of itself as contrarian relative to the rest of society. So you could plausibly see some preference cascades. Maybe these elites are side-eying one another and saying: is this really what we wanted? And is Elon OK? But they’re reluctant to be the first ones to speak out. Once some do, however, others will follow. This would be sort of the reverse of the process that played out from 2021-2024, as Silicon Valley elites became increasingly vocal about their opposition to wokeness and other things they associate with progressives and Democrats.

But LIFO might not be right; sometimes the new converts are the most passionate ones, after all. The more radical possibility would be that Trump instead loses support among his base, the white working class. Tariffs could have a bigger impact among manufacturing-dependent states, for instance, since they import many of their raw materials from abroad and since the tariffs are being reciprocated. Or if Democrats play their hand right — don’t worry, Republicans, because they probably won’t — a more left-wing flavor of populism could make inroads among this group; it’s not like Silicon Valley is naturally aligned with their interests, culturally or economically. Meanwhile, Trump’s approval ratings on the economy are worse than at any point during his first term, and voters might not forgive a tariff-induced recession in the same way they gave a pass to the sharp but brief COVID-triggered recession of 2020.

So, while the strong base case is that Trump indeed has a high floor, the history of presidential second terms suggests not to make too many assumptions about how low the numbers might go.

Goodbye West Side, hello East Side.

We’ll make a slight exception for George W. Bush since our database only contains one poll before Feb. 1; we’ll start him on Feb. 4 instead.

And I can’t say I blame them.

So basically throwing out any extremely short-lived fluctuations, in other words.

This condition is important because we’re evaluating the possibility that a president who was popular enough to be re-elected — in Trump’s case, after a four-year hiatus — nevertheless saw a lower floor in their second term.

Though partisanship might inhibit this throw-under-the-bus instinct, too. Democrats probably should be moving on from Joe Biden in every way shape and form, but instead he has his share of defenders.

Keep in mind there are push-and-pull factors here: Trump generally saw his numbers approve among racial and ethnic minorities, but Harris was seeking to become the first Black woman president.

I’ve noticed a lot of historical analysis when looking at Trump’s approval, and Dem’s chances for a revival. But, to me, this moment feels unique and unprecedented (I was born in the early 80s). Consequently, I keep thinking about a book I read in grad school called “Analogies at War,” which argued that leaders often draw the wrong lessons from past events. As a result, they frequently implement bad policies in the present, based, in part, on their faulty understanding of history.

Do you think there could be similar issues in public opinion analysis - where there’s a mismatch between present realities and past experience - or is there something about the field that makes it good at adjusting for political and cultural changes and staying current?

This was really good and just what I come here for! I recently read Dan Carter's super book, The Politics of Rage, about George Wallace. Wallace's populism is an interesting forerunner of Trump. although the book was written well before Trump appeared on the political scene, there are a lot of parallels (Wallace was a superb speaker, for example, able to read a crowd and get them worked up into a frenzy, his populism was a mishmash of ideas from different sources and not particularly ideologically coherent, he drew on white working class voters in a way similar to Trump, etc.) If we ever get a slow news week again (and those may be a long way off), I'd love to see you look at Wallace's support in 1968 as an independent candidate and in 1972 in the Democratic primaries and see if there's a connection to Trump's support. (I know that's a long temporal gap from 1972 and 1968 to 2016-2024, but some trends seem to be persistent.) In the meantime, I highly recommend Carter's book for anyone interested in the role populism has played long term in US politics and for its absolutely chilling description of racial issues in the 1950s and 1960s.