Discover more from Rounding the Earth Newsletter

“I couldn’t see where the collection of Burger King figurines fit in, but I supposed there was no reason why psychopaths shouldn’t have unrelated hobbies.” –Jon Ronson, The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry

In 2008, staff writer John Seabrook wrote about psychopaths in an article in The New Yorker entitled "Suffering Souls":

Psychopaths are as old as Cain, and they are believed to exist in all cultures, although they are more prevalent in individualistic societies in the West. The Yupik Eskimos use the term kunlangeta to describe a man who repeatedly lies, cheats, steals, and takes sexual advantage of women, according to a 1976 study by Jane M. Murphy, an anthropologist then at Harvard University. She asked an Eskimo what the group would typically do with a kunlangeta, and he replied, “Somebody would have pushed him off the ice when nobody else was looking.”

Amusingly, in the opening paragraph of an article in Psychology Today, psychology professor Dale Hartley wrote,

The Inuit people of Alaska have a word, kunlangeta, for “a man who … repeatedly lies and cheats and steals things and … takes sexual advantage of many women — someone who does not pay attention to reprimands and who is always being brought to the elders for punishment.” Anthropologist Jane Murphy revealed this in a study published in 1976. When she asked how the Inuit people dealt with a kunlangeta, one man told her, “Someone would have pushed him off the ice when no one was looking.”

Now, my point is not to have you guessing about whether or not plagiarism is a key aspect of psychopathy. It isn't. Plagiarism is likely more common among narcissists, including sociopaths. None of these things is the same as the other, and to the extent that there is any confusion, it should be pointed out that the entire history of clarifying these dangerous psychological abnormalities confuses even the professionals. As The Last Psychiatrist (TLP) once explained, the labeling of disorders changed from one DSM version to another, changing the entire philosophy of how we identify these conditions along the way. That TLP article further challenges the basic perspective of renowned psychopathy researcher Robert Hare.

My goal here wasn't to confuse you (media does a good enough job of that---can we even watch TV without somebody verbally treating psychopaths and psychotics as the same?) or to point out how confused professional psychologists and psychiatrists might be in their explorations of fundamental questions of human psychology. So, let's take a step back. The Seabrook paragraph was simpler, and to the point: there are people who, despite the basic societal structures and hierarchies that define and enforce boundaries, behave horribly toward other people. Psychopaths are rare people who neither feel empathy toward their fellow humans, nor care about societal norms. On an evolutionary scale, it might very well be the case that the occasional kunlangeta helped a tribe survive conjugation by another---the ones whom you might count on to do the dirtiest of dirty work. But implicit in such a hypothesis is a chicken-and-egg problem that may simply predate humanity. For the most part, humanity got along by pushing the kunlangeta off the ice.

Most people know the chilling tales of the psychopaths most talked about in Seabrook's article---the 15 to 20 percent of males in the prison population, some of whom commit crimes so baffling that the mental friction of conception (for most of us) allows late night comedians to entertain us with jokes about them.

I saw a girl crying, so I approached her, knelt down to her level and took her hand gently in mine. After a moment, I asked, "Where are your parents?" Then she cried even harder. I love working at the orphanage.

No, you're not a terrible person if you laughed. The resolution of the mental friction gets us. At least until it doesn't. When you've stopped laughing, it means the friction has resolved.

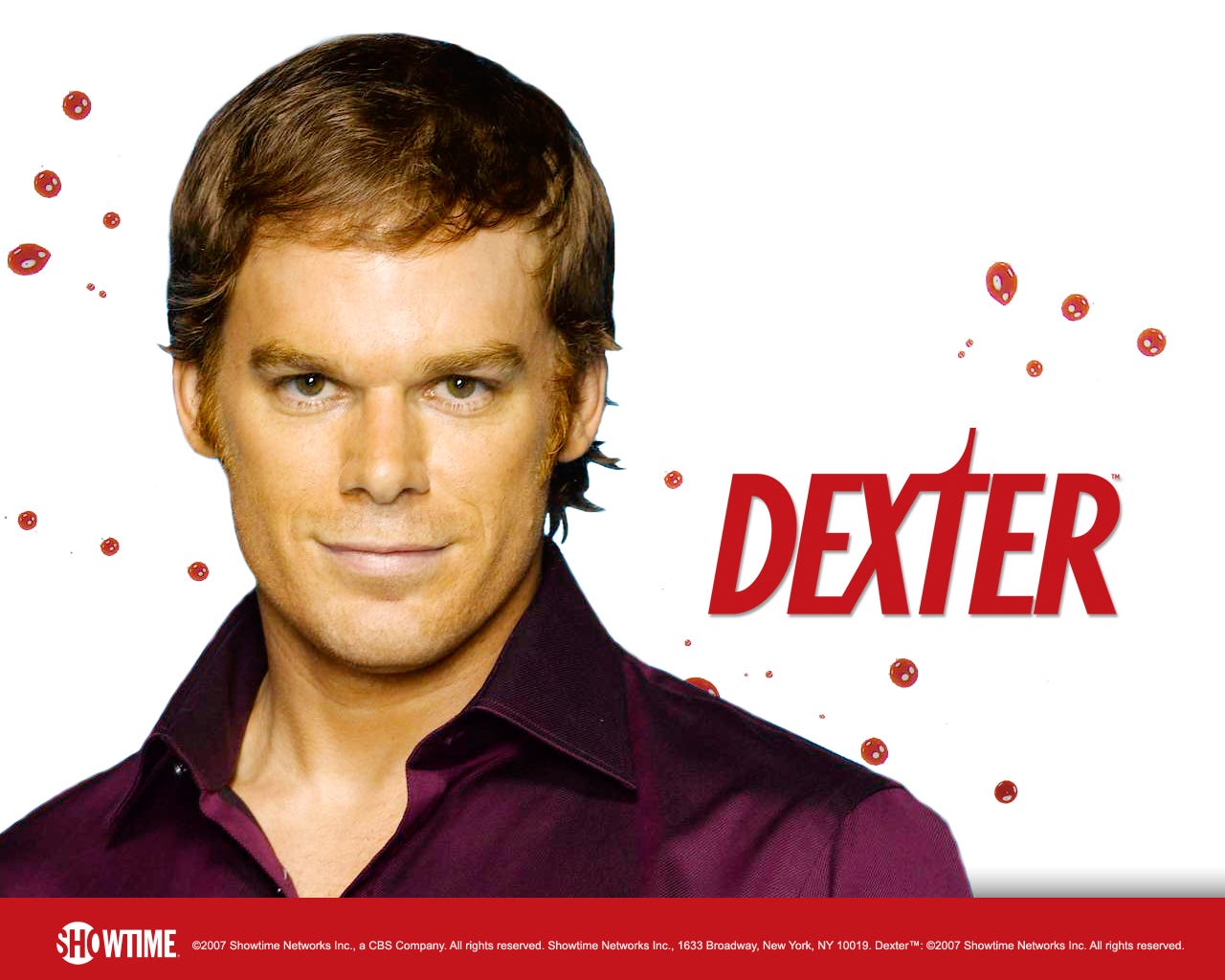

What most people understand less is how the same deviation of human psychology found perhaps 20 times as often among the hardest criminals coincides with perhaps similar proportions of corporate CEOs, lawyers, and media professionals. (image source: Lionsgate Films)

Perhaps the simplest explanations are intelligence or upbringing or both. It makes perfect sense that the smarter psychopath doesn't waste his life (his only because nearly all psychopaths are men) strangling the neighbor over the remote control. It makes perfect sense that parental guidance can frame the course of life for a child whose perceptions of the world need help in framing. Such was the subject of a popular cable television series you may have watched.

Let's now think on a larger scale. Why would roughly 4% to 12% of CEOs be psychopaths (I've seen as high as 20% claimed, implying psychopaths might be statistically around 25 times as likely to become CEOs)? What is it about the human condition, or this era of civilization, that pushes the most potentially destructive people to the top of decision-making hierarchies? Is there some process inherent in the machinations of life on Earth that allows for this, and that we can deconstruct in order to prosper in a new era of happier, healthier, and less existentially dangerous living? Is there a way to decentralize power so as to limit the damage psychopaths might do, or better encourage hierarchies of competence and wisdom?

Ultimately, these are questions of game theory, of which I plan to write much about when time permits. Until then, a study of corporatism might prove revealing.

I am a retired clinical psychologist who worked for several years in the correctional system in Australia. (And BTW, I was trained in the use of the Hare psychopathy assessment, and found it very interesting and useful). And I will tell you now, one of my greatest learnings from that period of my life was that there are more psychopaths on my side of the bars than inside. And I don't mean the correctional officers - though you might find the odd one there. Look at the management...

That figure of 20% among inmates is not correct. True psychopathy among inmates is actually fairly rare (probably higher if you are talking about a maximum security unit though). OTOH, the highest numbers of psychopaths are among the powerful elite - whether business or government or institutional. I think it is the power that attracts them. That, plus the fact that you need to have a certain amount of moral flexibility to get to the top. I have never personally worked in parliament, but from what I have heard, it is almost impossible to succeed if you have ethical principles that you stick to.

In my youth I was an investment banker with a top New York firm. I hailed from Houston, grew up in a middle class Catholic family (Dad was a senior manager at Exxon but not quite corporate executive level) and got an engineering degree at Rice. Spent a couple years out of college at Exxon, then went to Wharton and from there, Wall Street.

I was always struck by how different the people in finance were from the folks I grew up with. It wasn't really intelligence, although that may have been some of it. After all, Rice is an elite school and I would say the intellectual caliber there was at least as high as at Wharton, although arguably a bit lower than the investment banking average. It was more a certain coldness, a lack of empathy in my finance colleagues that struck me as being bizarre. Cold fish. Not true of all of them but true of a pretty high percentage, certainly much higher than in the general population.

After about ten years I left investment banking and returned to the land of the humans. Much happier for it. I remember joking with friends (not in the business) that many of the folks I used to work with would have made great hit men. I may have been on to something.