I think you can tell what kinds of things people have dreamed about for nearly the whole of the time we've existed. All you have to do is look at myths and legends. They're full of things like incredible strength, flight, speed, and magical powers. I'm going to stick mostly with European myths — especially Greek — simply because I know them the best. But myths from other cultures often include the same themes.

Deadalus, for example, was a legendary inventor who constructed wings for himself and his son Icarus to escape the island of Crete, where they were prisoners. They flew away. The part of the story that most people concentrate on, to be sure, is where Icarus flies too high, melts the wax holding the feathers on his wings, and crashes. But there's another angle to the story: the wings worked. Deadalus and Icarus both flew. And Deadalus, who didn't fly too high, succeeded in his escape and made it to the mainland.

The dream of flight inspired art as well.

The dream of flying is a big deal in mythology. It's something the gods could often do, as well as magical creatures like dragons. Pegasus, the winged horse, could fly, too. The dream of flight inspired art as well. John Keats wrote about flying in 1819 (Ode to a Nightingale):

Away! away! for I will fly to thee,

Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards,

But on the viewless wings of Poesy …

So did Emily Dickinson (Delight is as the Flight):

Delight is as the flight—

Or in the Ratio of it,

As the Schools would say—…

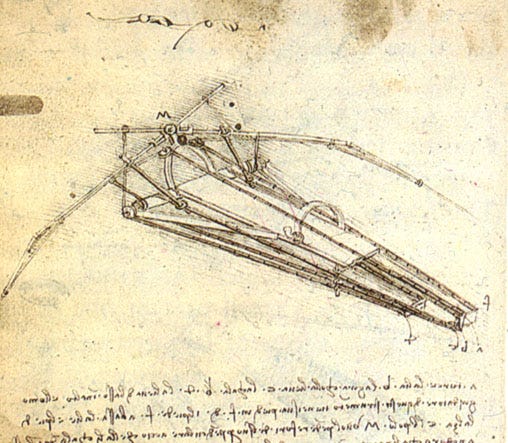

Flying has been a dream for a long time — I don't mean a dream in the sense of mental images while you're asleep; I mean a stretch of imagination. Imagination doesn't just inspire poets and painters, though; it's also the source of inspiration for builders and designers. Leonardo da Vinci is one of the most famous in European history, and he designed a flying machine that worked like a bird by the operator flapping wings. Not only that; his notes also include drawings for a kind of helicopter, a parachute, and a hang glider. Back in the day, it seems like people had a lot of dreams.

Da Vinci’s flying machine design from about 1488.

Then the dreams began to come true. Not a major milestone, but a milestone nonetheless; on January 9, 1793 the first flight happened in the Americas. The flight was made by Jean-Pierre Blanchard, a French balloonist (the first to cross the English Channel in a balloon) who took off from Philadelphia and landed in New Jersey. It wasn’t the first balloon journey, nor the longest, nor the most notable except for where it happened. Even in 1793, flight was passing from its dream state to…maybe even then starting toward the mundane.

Leonardo would probably have come up with one eventually.

On another January 9, in 1923, Juan de la Cierva made the first flight in a new type of aircraft he had invented: the "autogyro." It's a sort of hybrid of an airplane and a helicopter. Its propellor provides forward thrust, not vertical, but instead of fixed wings it has a rotor. The rotor isn't powered by a motor; the air moving across spins it and provides lift. It sound like it wouldn't work, but it does, and you can still find them occasionally. Autogyros can take off and land in very short distances, so they’re in use in specialized situations. Leonardo would probably have come up with one eventually.

As far as long-range, high-altitude powered flight, the famous British Lancaster bomber from World War II also had its first flight on January 9 (in 1941). It became one of the most-used bomber aircraft in the Allied fleet, and Lancasters made something like 150,000 flights during the conflict. It was by some measures better suited to the eventual atomic-bomb missions over Japan than the Boeing B29 that was actually used. But reportedly the man in charge of the mission, US General Groves, insisted on using a US-built plane. By that time, flight was far from a miracle. It was just another political football.

Rapid developments in airplane design and power during WWII led to a huge expansion in commercial aviation after the war. That leads up to the present, when billions of people around the world have actual, personal access to the ancient dream of flying. You don't have to dream about flying any more; all they need is to save up some money and buy a ticket.

And if you don’t have to dream about flying, you probably don’t. Now you can know exactly what it's like to fly, and you probably do — even if you haven’t personally flown. Admittedly, it’s not the kind of flying most ancients dreamnt about; now it mostly involves standing in lines, then sitting in an easy chair miles above the ground. So what happens to our dreaming? Not, again, when we're asleep. I'm talking about imagination. What do we do with imagination now that we can simply fly? We can speed along at tens of miles per hour on the ground? We can see sights hundreds or thousands of miles away? We can speak across oceans to our friends and family? Where are our new myths going to point us? In gaining so much, have we also lost something ?

Maybe one answer lies in considering where the old dreams of flight were going to take us. Deadalus and his son only wanted to get off an island. But some mythical fliers aimed higher. They ascended to new planes of existence: Heaven, Mount Olympus, Asgard, and the like. And maybe January 9 has a hint for us here, too. After all, it was January 9, 1992 that Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced the first observation of planets outside the solar system. Sure, those particular planets are orbiting a pulsar (PSR B1257+12 to be specific) so they're almost certainly the opposite of hospitable. But still.

Illustration of planets around pulsar PSR B1257+12 by Pablo Carlos Budassi.

Now we know there are planets out there. Way out there. So maybe there's a myth slowly forming in our collective subconscious, and maybe there really are things left to dream about. At least would be better than just staring at your phone all day, right? Especially since the iPhone was introduced on January 9, 2007.