Today is the 95th anniversary of the debut of Fritz Lang’s silent film Metropolis. It’s still worth watching; several surviving prints have been restored, and you can find color and monochrome versions on YouTube. Metropolis, 95 years later, is a weird juxtaposition of the future as seen from the past. It takes place in a city full of skyscrapers, where workers and managers occupy two extremely different classes. You can see plenty of parallels with the economic inequality that’s today’s reality in the US. On the other hand, the world of the film, like most fictional realms, is simple. There’s a single hero, a single villain, a couple of plot twists, and most famously, a robot temporarily disguised as a human. So it’s a pretty good match for some of what 1927’s real future would hold — and yet in other ways it’s a complete miss.

You might see that juxtaposition of truth and untruth, beginning and ending, positives and negatives as something of a theme for January 10. It’s been a day of echoes and mirror images, premonition and recollection, futures and pasts, fulcrum points at which things changed — or at which things could have changed but didn’t.

A popular metaphor used for moments when things change and there’s no going back is “Caesar crossing the Rubicon” — it was the event that’s credited, at least metaphorically, with the beginning of the end of the Roman Republic. And there’s a juxtaposition right there: the “beginning of the end.” Anyway, it really happened, and today was the day.

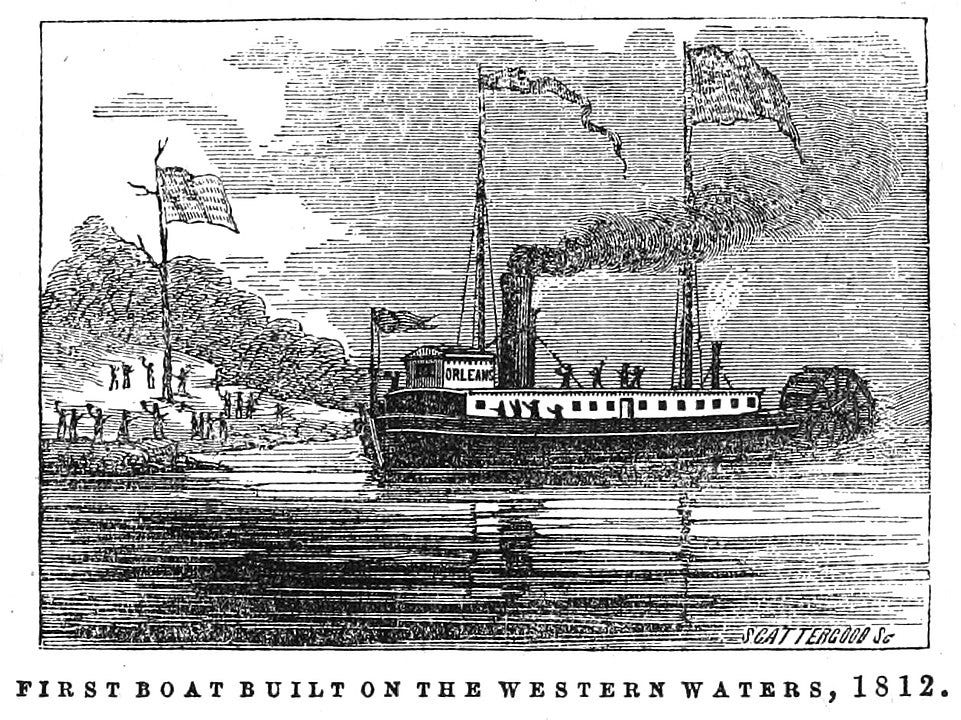

This has been the day when other things changed too; more beginnings of more endings. In 1812 the first steamboat on the great central rivers of the US, the Mississippi and the Ohio, finished its maiden voyage from Pittsburgh to New Orleans (steamboats were already plying eastern US waters). She was the New Orleans, and the man who had invented the thing, Robert Fulton, was part owner. The journey took nearly three months, but proved it was possible. It ushered in a future of river transportation in the central part of the US — two years after the voyage, there were 60 steamboats on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

The New Orleans steamboat. By David Scattergood

January 9, 1863 ushered in another future featuring transportation different from what it might have been before. It was the day the Metropolitan Railroad opened in London. It was the first underground railroad in the world, and it was propelled by steam locomotives. Did I mention it was underground? That worked out about like you might expect; the stations and tunnels were, reportedly, not the places you’d choose for a breath of fresh air. Because the designers had expected, for whatever reason, that the trains to be used would be smoke-free, not much ventilation was designed in. Before long, though, the underground smog prompted additional vents. For the most part the vents were just holes drilled from the tunnels to the surface and openings made in the roofs of the stations.

It’s almost impossible to tell what all the effects are from an inflection point in history. Did the unanticipated smog in the first underground railway inspire people to pay more attention to the environment and to ways of cleaning the air? I have no idea. But on January 9, 1877, Frederick Cottrell was born in Oakland, CA. He grew up to be a chemist and inventor, and in 1907 applied for a patent on his latest creation: the electrostatic precipitator, which reduces pollution by removing dust and smoke from the air without needing a filter. That was a bit of an inflection point in itself; Cottrell’s systems have been installed in factories and industrial plants worldwide, and the electrostatic system is still the most important process for cleaning air. By the time the electrostatic precipitators arrived, though, the London Underground had already switched to electric power.

Rockefeller became a real-life version of the ultra-rich upper crust portrayed in Metropolis.

But if January 10 can list some environmental wins, it has equivalent black marks against it, too. It’s the day in 1870 that John D. Rockefeller incorporated Standard Oil. It played a leading role in commercializing petroleum products, in the process turning up the pollution dial and turning Rockefeller into a real-life version of the ultra-rich upper crust portrayed in Metropolis. I’m not sure whether it’s irony or coincidence — okay, maybe “ironic coincidence” — that January 10, when Standard Oil began, is also the day that the first oil well gusher kicked off the Texas oil boom. Before that, oil in the US mostly came from Pennsylvania.

The gusher happened at what came to be called the “Spindletop Oil Field”, and although it wasn’t drilled by Standard Oil, Rockefeller’s company tried to move into the state right away. But Standard Oil was already unpopular because of its near-monopoly on the petroleum business in the eastern US, and they were partially blocked from entering the Texas oil business from the bottom, by popular sentiment, and from the top, by state laws. Some of the laws were passed specifically because of Standard Oil and their business practices. So it was the way the biggest oil company ran its business, trying to keep competitors out, that led to companies like Texaco and Gulf being able to enter the very same business as competitors. Typical January 10 outcome, right?

January 10 has seen some major conflicts begin, like the Roman civil war, but that’s balanced by some endings. It’s the day the Treaty of Versailles ended World War I. It’s also the day people tried to do something about the wars that constantly arise; on January 10, 1920 the League of Nations agreement took effect, and also the day in 1946 marking the very first United Nations assembly. They didn’t have the iconic UN building in New York yet, of course, so they met in the Methodist Central Hall in Westminster, London. That hall has been (and is) the site of many well-known events, from political rallies to concerts to stage productions. And just to add one more weird juxtaposition: the Central Hall is a facility of the Methodist Church, which promotes abstinence and doesn’t allow alcohol in their buildings. Except that the Methodist Central Hall serves alcohol in their café and at conferences.

So maybe the story of January 10 is just some sort of bouncing back and forth between one extreme and another; between a binary one and a binary zero. Maybe that’s why it was the day in 1946 that the US Signal Corps began Project Diana, which bounced radio signals off the moon and collected the echoes back on Earth. That’s January 10 in a nutshell; a day haunted by echoes.