It’s only logical that we talk about January 14 today. For one thing, it really IS January 14, so there’s that. But it also happens to be World Logic Day. It’s a UNESCO-declared “international day”, but in fact “Logic Day” happened before the UNESCO declaration. Not only that but — and I’ve checked this out very carefully — it was an actual day before the declaration too. But I don’t meant to belittle UNESCO, who are if nothing else, very well-intentioned. So making jokes at their expense just wouldn’t be logical.

In fact, now that I’m thinking about it, I’m not sure that jokes are logical at all. After all, many kinds of humor are funny because there’s a situation or story, you think you know what, logically, is coming next, but then there’s some sort of twist. Not logical at all, but, you know…funny.

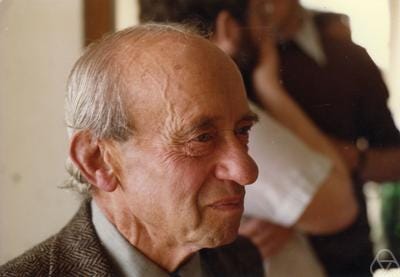

Logicians are generally not considered funny, sad to say. In fact today is Logic Day because of two of them. One, Alfred Tarski, was born on January 14, 1901, in Warsaw. When he was in the equivalent of high school people began to notice that he was pretty gifted in math, but — and this seems illogical — when he enrolled in the University of Warsaw in 1918 he declared his major to be biology. He crossed paths with a world-class mathematician and logician though, who probably taught one of Tarski’s required classes.

The teacher, Stanisław Leśniewski, talked Tarski into abandoning biology in favor of math and logic, and by 1924 Tarski had earned a doctoral degree in his new major. In fact he was. the youngest person ever to do that at Warsaw University, and joined the faculty. As an academic, he gradually developed contacts and friends around the world as he published papers and attended seminars, and in 1939 he was invited to address the Unity of Science Congress at Harvard. Remember that in 1939, events were unfolding in Europe that weren’t logical in the least, and boded quite ill for Poland. And even worse for Polish Jews, which is exactly what Tarski was.

They first met in 1930.

It turned out that Tarski left Poland on the very last ship that left Poland before it was invaded, the event that that marked the beginning of World War II. That kind of luck defies logic, I know, but there it is. Tarski’s luck had its limits, though. He didn’t bring his wife and children to Harvard with him, and as a result he didn’t see them again for seven years. They did survive the war, although he lost most of his extended family in the Nazi holocaust.

Tarski’s trip to Harvard eventually became permanent; he became a US citizen in 1945. One of the people Tarski met in his travels in Europe prior to the US, though, was Kurt Gödel. They met in 1930 when Tarski lectured at the University of Vienna. Now, logic, at least the garden-variety sort that most of us are comfortable with, sometimes deals with balance between two values. And remember that World Logic Day is on January 14 because of two logicians. Tarski is one, and the other is Kurt Gödel. January 14 is Logic day because it’s Tarski’s birthday — and because it’s Gödel’s death day (in 1978).

Gödel was born in the same era as Tarski — 1906 and 1901, respectively. Both were born in central Europe, became prominent academics, and escaped to the US in 1939 just as the war was breaking out. In Gödel’s case, he traveled with his wife, and they traveled east instead of west. They took the Trans-Siberian Railroad to the east coast of Russia, then sailed from Japan to San Francisco. After that, it’s unfortunately not logical at all because Gödel, who arrived on the west coast of the US, spent the rest of his career at Princeton in the east, while Tarski, who arrived on the east coast, lived and worked in Berkeley, in the west.

In both men’s experience, though, an enormous motivating event was World War II. Although neither was directly involved in the war efforts in Europe or the US, the war was the reason they ended up in America and both became US citizens — Tarski in 1945 and Gödel in 1947.

By the way, while he was studying for his citizenship exam, Gödel discovered a logical problem in the US Constitution that would allow the US to become a dictatorship. As luck would have it, the presiding judge at the exam asked Gödel about the government of his native Austria. Gödel answered that it had been a republic, but the constitution was changed to make it a dictatorship. The judge said something like “yes, but that could never happen here,” and Gödel nearly sunk his chances by saying “Oh yes it can, and I can prove it.”

Luckily the judge was a friend of Albert Einstein — as was Gödel himself — and Einstein was right there in the room with them. He had prepped the judge by telling him that Gödel could sometimes go off on tangents like that, so the judge basically ignored the whole thing.

The notion that there’s a logical flaw in the Constitution became known as “Gödel’s Loophole,” and people have been thinking about it — and searching for it — ever since. Because the judge didn’t let Gödel explain, and in fact he never did, not to anyone.

Speaking of constitutions, though, it turns out that January 14 is the day in 1639 that the Fundamental Orders were adopted by the Connecticut Colony council in what eventually became the state of Connecticut. The Fundamental Orders were a set of rules about how the group of towns along the Connecticut River would govern themselves. As far as anyone knows, it was the first time in history that a written constitution formed the basis of a government. The Orders eventually became one of the bases for the US Constitution, and included a delineation of the rights of an individual. And that was embodied, a century and half later, in the US Bill of Rights.

Would they accept a surrender?

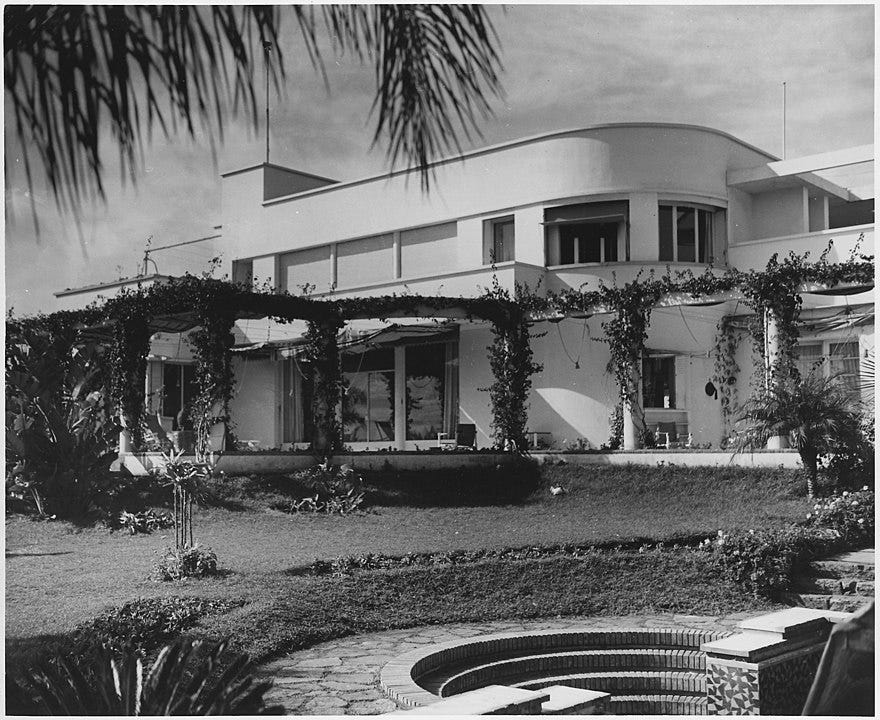

But let’s jump back, for a moment, to World War II, which propelled our two logicians to the United States. By 1943, the war’s tide was turning in favor of the Allies, and two of them — the US and England — decided their leaders ought to meet and decide on what exactly they were going to do to end the war. Would they accept a surrender? Under what terms? Or would it be a fight to the death, only ending with the complete destruction of Germany and its allies? Those were the questions on the table when Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill met at the “Casablanca Conference”, which really was held in Casablanca, in the Anfa Hotel. Now, the war wasn’t over yet, and although the allies had driven the German army out of northern Africa, there had to be a certain amount of danger associated with holding the meeting in Casablanca rather than, say, Washington DC or somewhere in England. Or even on board a battleship. Yet Casablanca it was. And since it’s Logic Day, I think we need to ask why.

This is entirely speculation, and completely illogical. Probably. But I can’t help noticing that if you consider World War II and all the cultural icons, legends, and stories that came out of it, a big one is the film Casablanca. In that movie, great decisions are taken and potentially world-changing events are inspired, and they all pivot on one tiny location in northern Africa: Casablanca.

Another bit of the puzzle, whether logical or not, is timing. Roosevelt’s and Churchill’s Casablanca Conference took place on January 14, 1943. And the movie? It was released on November 26, 1942. Who’s to say that Roosevelt and Churchill both saw the film, got just a bit wrapped up in the romance of the story, and jointly decided that if they were going to get together to figure out how to end this damned war, it was going to be right there in Casablanca. I mean, it’s only logical.