Discover more from The Eucatastrophologist

One of the clearest ways to understand any culture is to notice what’s not allowed. But we now seem to live within a global society that finds prohibitions distasteful, if not outright repulsive. I am thinking here of the recent tantrum-throwing at the return of a prohibition after the fall of Roe v. Wade in America. Real tantrumocracy hasn’t been tried, mind you, but the USA is certainly getting there. The sociologist Philip Rieff suggests that the West has increasingly moved away from culture itself because prohibitions are prohibited. We live in an anti-culture now, he suggests. The famous 1968 protest slogan ‘It is forbidden to forbid’ is almost a unifying principle in contemporary cultural production. If at one time, sordid content in films and television was the exception, now it is the rule. Even entertainment aimed at children frequently includes subversive, often violent and sexual elements, not suited for children—as many a discerning parent of young children can attest. Disney’s latest attempts at social engineering are just the tip of the iceberg.

Now we are tangled in the electricity of anything and everything, always happening as incessantly as possible. This is the nihilism that emerges from excess, the sheer positivity of no stopping—of self-exploitation and high performance subjectivism. All of this is nicely packaged in images and fragments of information. Memory disintegrates as narrative is increasingly replaced by the pointillist unreality of data and information. Transparency is also normalised to a strange degree. Selves, alienated from themselves, objectify their shallow inner worlds even as their faces are replaced by mere physiognomic markers. Our phones are objects of constant attention that, while we pay attention to them, transform personhood into a tool of some invisible surveillance machine. Everything becomes informationalised—without context and meaning and easily exploited by the logic of the market. According to this logic, hazards and hindrances must be done away with as quickly as possible. If you’re feeling low, get a drug. Feeling sick? There’s probably a pill for that? Plague? Try this heavily ethically compromised vaccine! In a society of excess positivity, the chief function of the social realm is to lubricate everything, to transform a world of hesitations and questions into absolute immediacy and life into a mere impersonal process.

The old world of etiquette died ages ago. I think of the perpetual suspicion of norms now—especially, owing to various Freudian slippages, around sexuality. Of course, anti-culture, or at least some sort of counter-culture, has always been a component of culture. Every civilisation has had its brothels and back alleys, its adolescent rebels and grown-up degenerates. Every society has found people and forces within it that challenge its limits. But in a society shaped by the modern liberal inversion of act and potency, we find ourselves deteleologised, and so also without edges. Oswald Spengler’s view that Western man’s essence is Faustian is spot on. The soul of the West fosters a desire for limitlessness, which amounts to a desire to escape the boundaries of being itself.

One of the often unrecognised consequences of this is a widespread tyranny against interpretation. If everything is smooth and instant and rapid, understanding becomes abhorrent and monstrous. We should not understand, we should simply act! We should be practical. A friend told me in a conversation the other day about some advice he’d heard that relates to this meta-injunction; the advice was, “If you have dreams for your career that your spouse doesn’t support, just get a divorce.” How practical! Marriage itself disappears under the reign of excess positivity. In a similar vein, I have been fascinated by the responses of liberals to the fall of Roe vs. Wade. It would be the perfect time for American leftists to revisit questions around the ethics and legitimacy of that now removed law. But no. Argument has been replaced by slogans. Slogans are smoother and conform better to the expectations of a society of excess positivity. Arguments require negativity and careful thought. They are too much work for the culturally indoctrinated. Here’s a meta-slogan for our time: Don’t just think there, do something!

The trouble is, pragmatics are already embedded in invisible theories and unconscious metaphysical assumptions. And if we are not allowed to understand our own theories and assumptions, if we are forced to not know what we are doing, we become absolutely subject to current-thingism, or to whichever machine and/or meta-machine happens to be running the show. It is a basic fact of life that at some point you will need to choose a philosophy, or you’ll have one chosen for you. I realise that even touching on the Roe v. Wade matter is risky. It is a hot topic, and hot topics are perfect for a society of excess positivity. Still, for the moment, what interests me here is that the pro-abortionist all too neatly conforms to the anti-culture’s hatred of interpretation and meaning. What is a child for child murderers, then, but an unbearable light on their hermeneutical ignorance? What is a child but a limit on those aspects of ourselves that want to remain childish? What is a child but the real other, the non-consumable other?

Excess positivity can only foster ignorance. And ignorance does not make for a good life. “The unexamined life is not worth living,” says Socrates to us even now. Given all the excess positivity, it’s no wonder we live within a support system for adolescent minds, the state of being certain without understanding. You can, as far as the rule goes, believe whatever you want. What you live for should be merely a preference. Why not self-identify as a cabbage now? By the magic of the woke will to power, it would be ‘wrong’ if anyone batted an eyelid if you did. Having been deteleologised, having been robbed of aims, there is no way in a society of excess positivity to effectively tell if anyone is missing the mark. This is how slippage gets a grip. Unsurprisingly, excess positivity can only foster moral decay. One function of excess positivity is to eradicate any inkling of sin or guilt and replace it with likes. To live in an anti-culture, then, is to live in a sibling society—a world in which the absence of clear limits is (I say this in full recognition of the irony) a defining feature. Adults and political order are not allowed, only toddlers with their proposal of tantrumocracy.

One common explanation for the loss of limits is the advent of postmodernism. Postmodernism, however, is a figure. The ground and reason for that figure is something else. Spengler’s insight into the modern West as Faustian already suggests this. Like him, G. K. Chesterton saw the loss of limits as endemic in modernity well before the masters of suspicion and other deconstructionists got a hold on the popular imagination. In his 1905 book Heretics, he tells a parable of a monk who represents the spirit of the middle ages. The monk wants to discuss the value of light with a small crowd of people at night. Everyone stands under a lamppost. The monk tries to speak but he is suddenly knocked down by the crowd. His carefully considered arguments are not heard. The people soon also tear down the lamp post and quickly congratulate each other on what Chesterton refers to as their “unmedieval practicality.” They soon discover, however, that their reasons for ending the rule of light are wildly at odds with each other. Some, for instance, wanted the light gone because they wanted to hide their wicked deeds, while others wanted the iron from the lamp post and still others just wanted to tear something down. And so, after all that, they soon discover that the monk was right. They needed to first figure out the nature and value of light. But they are left to do so in the dark.

In his 1908 book Orthodoxy, Chesterton attends again to the importance of boundaries. In fact, this theme is detectable throughout his life’s work. In Orthodoxy, he writes, also parabolically, of some children who love playing on the flat, grassy top of a small island in the sea. “So long as there was a wall round the cliff’s edge,” he says, “they could fling themselves into every frantic game and make the place the noisiest of nurseries. But the walls were knocked down, leaving the naked peril of the precipice. They did not fall over; but when their friends returned to them they were all huddled in terror in the centre of the island; and their song had ceased.” Everyone with any level of sanity knows that boundaries do not have to be thought of as tyrannising us. The boundaries around a playground ensure the joy of play. Importantly, they represent a certain understanding of the world.

In the same vein, in his 1929 book The Thing, Chesterton discusses an idea that we now know as Chesterton’s fence:

There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

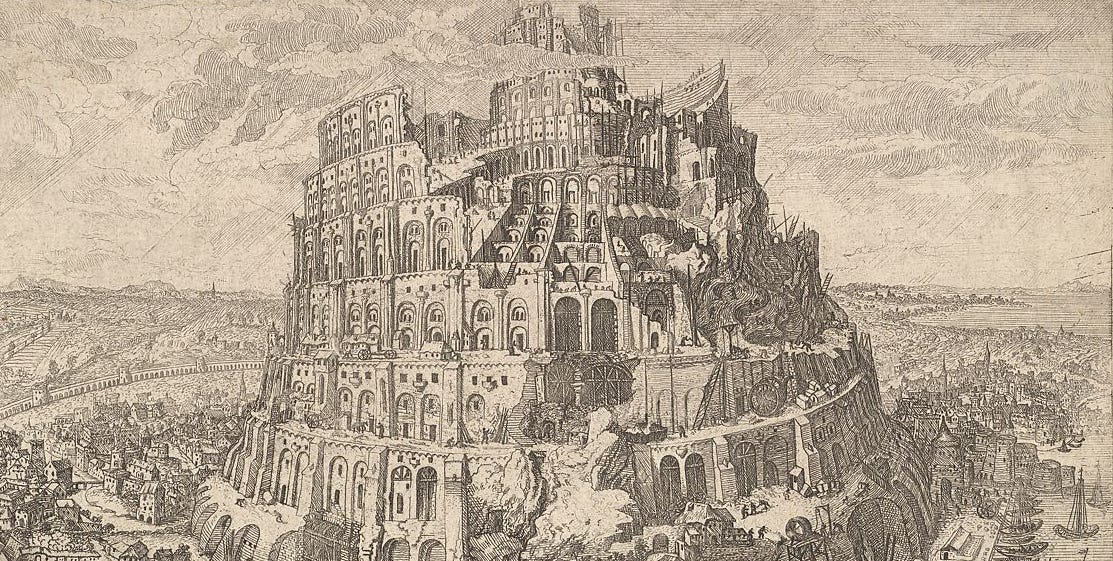

This principle can be stated simply: Don’t remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place. Crucially, Chesterton observes the core gesture of excess positivity: “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” In response to this, he suggests something else: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think ...” Chesterton proposes interpretation itself as an antidote to excess positivity. This is an echo of one of the morals of that ancient biblical story of the Tower of Babel. The building of that tower is a symbol of uniform agreement—of excess positivity. God’s judgment on those ideologues is significant: he causes everyone to speak different languages, and thus stresses the vital importance of interpretation. If you want the world to be meaningful to you, you must interpret it. If you want to be alive and not merely a cog in a machine, interpret the world.

The electric world renders us especially comfortable with only what is immediate, even while we are encouraged to repress the recognition that immediacy itself is mediated. Excess positivity means that what shows up in news feeds and personal radars appears as it is, as if it is all there is in its absolute immediacy. This is why fake news works. It is perhaps even more effective nowadays than real news because of the general environment of positivity. Real news requires interpretation, after all. Fake news does not. Make any claim you like and someone, somewhere will believe it. Against this, Chesterton’s fence operates as a moment of hesitation and lingering. It proposes that we should ask the question: What does this or that thing mean?

There is a lot to this that is worth exploring. In fact, I have written a book on Chesterton’s unique interpretive awareness that you can go and read if you’d like to. Still, to come to a conclusion, I want to pick out one thing that is particularly pressing for us in this age of excess positivity, which amounts to little more than a lazy minding of being. To recover interpretation means to relativise our relationship with it and to be humble even in our understanding. As Jacob Phillips writes in his essential Obedience is Freedom (Polity, 2022):

By acknowledging that everything in your own perspective is coloured by that perspective, it becomes possible to accept that there are other perspectives at the horizons of one’s own. … To interpret is to be between different accounts of a thing, situated from subjectivity in relation to objectivity and surmising how best to aim at the latter.

This is significant. In a society of excess positivity, the loss of interpretation also implies a loss of relation—of betweenness. The common attack on diversity of thought is one signal of this. But if I know that you think exactly the same thoughts as I do, why would I bother having a conversation with you? Interpretation restores to the world a sense of the wonder of difference, and thus the possibility of a genuinely ethical relation, and of real relationships. As Phillips notes,

“Genuine interpretation is a relation of mutual obligation. The interpreter is obliged to approximate as best as possible to an objective interpretation of events, while simultaneously being obliged to be as attentive as possible to subjective perspectives. Blindness to either one or the other makes one side morph into a pseudo-version of the other.”

As this mention of “a pseudo-version of the other” suggests, the society of excess positivity, the society of immediacy, is a society of unreality. But anyone who takes even a moment to consider the many fences that have been torn down, the largest one being the fence of reality itself, they will soon realise something: To want to rid the world of all limits is not only to destroy understanding; it is to destroy the world itself, themselves along with it. To refuse to understand is to do violence to being and to beings. And so, of course, we may not agree with each other on everything. We are unlikely to every fully agree even with our closest friends and companions. But if we can understand each other, even if we differ from each other, we stand at least some chance of building something far less monstrous than the Tower of Babel.

Subscribe to The Eucatastrophologist

Discerning and interpreting the signs of our time