Discover more from Turtle's Pace

If I wasn’t sweating, I wasn’t working hard. This perspective served me well in entry-level jobs that required physical exertion, like hauling plants around a humid greenhouse. But it didn’t age well. As my career shifted to knowledge work, this “work hard” mindset translated to long hours in the office churning out high volumes of low-value labor—writing meeting minutes nobody read or creating spreadsheets of little substance. I applied a “blue collar” approach to a “white collar” profession, misbelieving I was working hard. Yet, paradoxically, I was following a lazy path.

Shortcomings of “Work Smart, Not Hard”

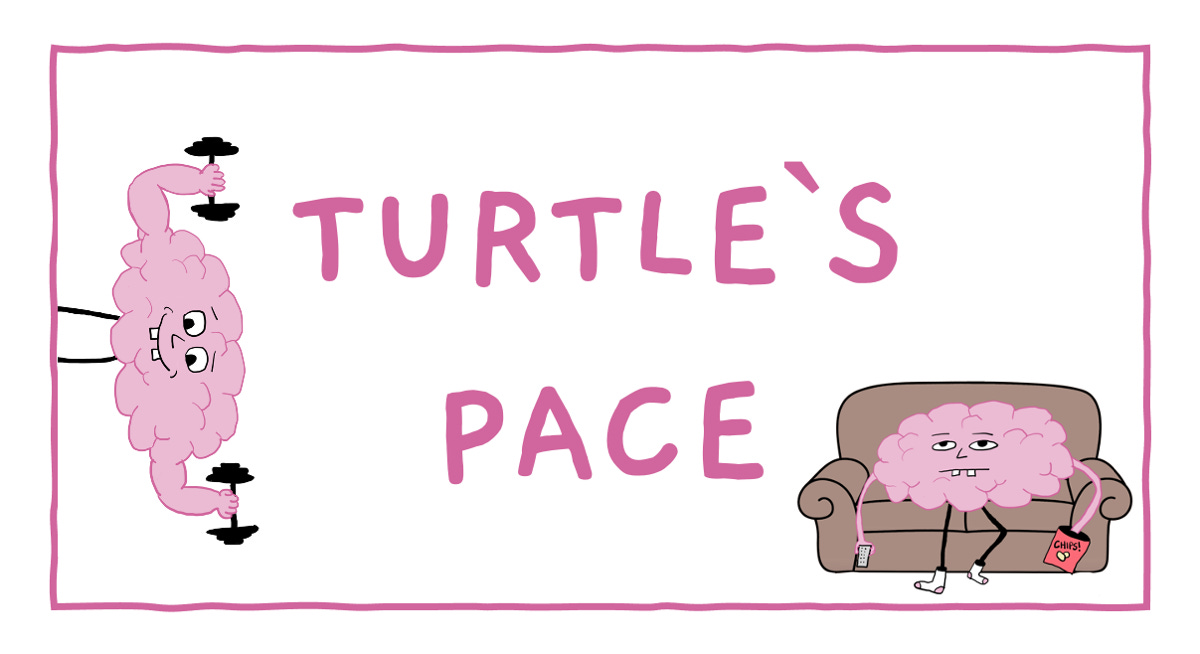

Some trite advice to my past self could be “work smart, not hard.” Don’t spend hours manually editing two thousand cells (yes, I’ve done this) when a twenty-character Excel formula could do it in seconds. While “work smart, not hard” is excellent for task execution, it assumes a basic premise: The work is worth doing. “Work smart” implies that the “hard” in “work hard” is the problem, but what if the real culprit was the “work” itself?

Lazy Thinking

Manually editing two-thousand spreadsheet cells is hard work in the truest sense, for when you finish, you’ll have eye strain and feel exhausted. But let’s not kid ourselves: the work doesn’t require much thought.

This brand of hard work is lazy thinking. You might not know why you’re editing this spreadsheet, or the task might lead to nothing, rendering your work useless. It’s not our fault that we fall into lazy thinking—most education systems at scale fail to teach us how to think hard. Some could argue this is a conspiracy to infantilize society and make us more compliant to authority—for which I’ll make no comment. To use Occam’s Razor, I think the simple answer is that education at scale is messy. Teaching critical thinking en masse is infeasible because the individual learners must want to put in the effort.

The Need for Thinking Hard

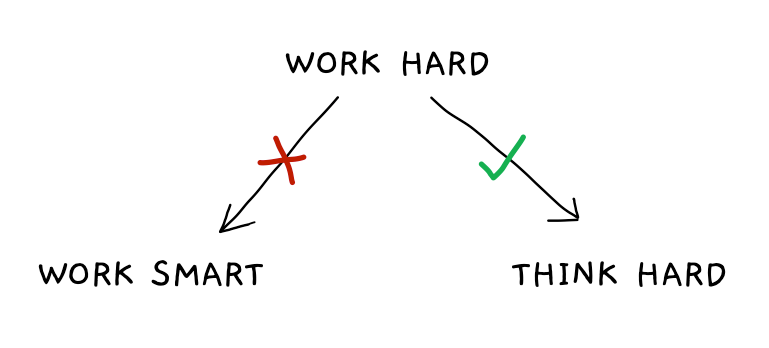

Lazy thinking is our default state—some might say it’s “natural” to let our monkey minds run rampant. While that’s more or less worked so far, the world has shifted from a need for physical fitness to a need for cognitive fitness. We no longer compete with large animals like saber-tooth tigers or endure unknown seas to discover new lands. Now we compete with manmade technology, be it highly efficient processes, sophisticated machines, or artificial intelligence, so we require more intellect, more “thinking hard,” to be effective.

Although thinking hard is a learnable skill, its fundamental cornerstone is concentration—of which we are in short supply.

Atrophied Concentration

Many believe that concentration is going extinct. 51% of UK adults believe the results of a controversial study from Microsoft in 2015, claiming that adult attention spans are around eight seconds. While the Microsoft study hasn’t been peer-reviewed or replicated, the perception remains that social media, pervasive smartphone access, and Big Tech’s “attention economy” create an environment unsuitable for sustained focus. Whether or not these factors—or other factors beyond our control—have atrophied our concentration, we don’t have to accept our weak state.

We can get off our cognitive couches and cultivate the ability to concentrate.

Developing Cognitive Fitness

When cognitively fit, we can work more efficiently to create time for the things we enjoy. We can reduce anxiety because we’re not victims of an untrained monkey mind. We can gain self-confidence as we learn to direct our mental energy to things we choose rather than things that are thrust upon us.

If 30 minutes of running can improve our cardio, could 30 minutes of reading improve our focus?

A Cognitive Fitness Routine

Here’s a “cognitive fitness routine” I’ve been following to strengthen my concentration muscles:

Pick a Concentration Habit. Like physical exercise, pick something that interests you and requires focus—such as reading or meditation. Do this activity every day.

Start Stupidly Small. If your attention span is only eight seconds long (I don’t know how you’d read this far if so), make your habit five minutes per day to establish your base.

Ramp Up Slowly. Each week, extend your period of focus. During week two, move to ten minutes per day. The following week, fifteen. Then thirty.

Take Breaks. Like resting between reps, take breaks between periods of focus. Consider the Pomodoro Method to timebox your concentration bouts.

Low Info Diet. No workout routine lets you eat with abandon since a poor diet will sabotage any fitness effort. If junk food’s in the house, you’ll eat it. If “junk media” is on your phone, you’ll binge it. I set usage timers on social media so I don’t doom-scroll for more than fifteen minutes daily.

Do this for a while, and your ability to concentrate—your ability to think hard—begins to grow.

Like any fitness regimen, maintenance is critical. It’s okay to splurge occasionally but stay committed to your cognitive fitness routine to keep those concentration muscles big, strong, and shiny.

Junk Drawer

If you miss my “Three Thing Thursday” style posts, consider subscribing to my friend Zvonimir’s 3-in-3 Newsletter. His posts have a similar humor to mine, they’re clever, and I always find something fascinating (like these zombie bugs).

The FBI Vault is an archive of sordid history if you’re seeking inspiration for your next fiction novel.

What is it that given one, you’ll have either two or none?

Subscribe to Turtle's Pace

Slow ideas for fast times

This is awesome! I’m totally in on this for sure. Omg ! Love the drawings. 🥰