Discover more from The Living Philosophy

Soren Kierkegaard — The Father of Existentialism

A deep dive into the philosophy of the Christian father of Existentialism

Kierkegaard was by far the most profound thinker of the last century. Kierkegaard was a saint.

— Ludwig Wittgenstein

For all its critical analysis philosophy has not yet managed to root out its psychopaths. What do we have psychiatric diagnosis for? That grizzler Kierkegaard also belongs in this galere.

— Carl Jung, Personal letter to Arnold Kiinzli, 28 February 1943

Søren Kierkegaard is best known as the "Father of Existentialism". But unlike many of his Existentialist peers from Nietzsche to Camus, Kierkegaard was not an atheist. He was a devout Christian.

But it was precisely in this faith that Kierkegaard's Existentialism expressed itself. His attitude towards Christianity was surprisingly similar to Nietzsche's. Like Nietzsche he had much love for Jesus and little respect for the Church with its priest-led herd. Disillusioned with this all-too-human institution there are two choices: atheism and mysticism. Kierkegaard chose the mystical path.

Across his career the core theme of Kierkegaard's work is faith. And faith for Kierkegaard is above all a personal relationship with a personal God. Another central element of Kierkegaard's philosophy is a preference for passion over reason. He saw faith as the "highest passion". It was something you lived. It was something that required action rather than logic and reason.

The Church disgusted him by keeping its congregation like children. His works were all dedicated to "that single individual," because it was only in the individual that the intense passion of faith could work itself out.

Kierkegaard's work as a philosopher was to ignite the same passion for living faith in his readers. He designed an elaborate stylistic method he called "Indirect Communication". This method used pseudonyms, and various stylistic devices to force readers to think for themselves. The many narrators in a single work contradicted each other. And so this style forced the responsibility back on the reader to think things through.

Kierkegaard's philosophical model was Socrates. In his Master's dissertation, Kierkegaard examined the Ancient Athenian philosopher's use of ironic questioning. This Socratic irony forced his fellow citizens to think for themselves. Kierkegaard designed his Indirect Communication to do the same.

Like Socrates Kierkegaard wanted to awaken a passion for living philosophy in his readers. Both thinkers wanted their reader/listener to go beyond the shallow ways of "The Crowd". They wanted them to become true individuals.

Kierkegaard saw himself as a Christian missionary in Christendom. His task was to convert members of "The Crowd" into true individuals of faith. This work of Kierkegaard is usually divided into three key phases: the First Authorship, the Second Authorship and his direct attack on the Church in the last year of his life.

The Making of a Philosopher

There have been few philosophers as fertile as Soren Kierkegaard. After finishing university in 1841 at the age of 28, Kierkegaard started his writing career in a very deliberate way. This first set of works — published between 1843 and 1846 — he called his "Authorship" (or in hindsight his First Authorship).

It began with his greatest masterpiece Either/Or in February 1843. Eight months later he published three books in one day. One of these books was Fear and Trembling — another one of his great masterpieces. The next June he published four books in a month. In total he wrote sixteen books in the space of three years.

Like Alexander Hamilton, Kierkegaard wrote like he was running out of time. And this is no coincidence. We can trace the origins of this prodigious writing career all the way back to the youth of his father. When Søren's father Michael was a starving shepherd boy on the Jutland heath he cursed God.

And for the rest of his life, Kierkegaard Snr. was wracked with guilt. He passed this guilt onto his children. And he came to believe that because of his blasphemy, he would lose all his kids before the age of Jesus's death at 33.

Søren grew up in the oppressive gloom of his father's melancholy and he inherited his father's guilt. The fact that his father had lost two wives and five children before Søren turned 21 didn't help matters. On his 34th birthday Kierkegaard expressed his shock at being alive in his journal:

How strange that I have turned 34. It is utterly inconceivable to me. I was so sure that I would die before or on this birthday that I could actually be tempted to suppose that my birthday was erroneously recorded and that I will still die on my 34th

This shadow of impending death was the fire driving Kierkegaard's creative output. But it was not the only one. The other major influence was his broken engagement to Regine Olsen. They first met in 1837 when Olsen was 15 and Kierkegaard 25. They were engaged in 1839 but within a year Søren called off the marriage.

The reason for this abrupt break was never explained.

In his journals we find mention of a terrible secret he was harbouring and couldn't face telling her. Olsen put it down to his religious vocation. We could also put it down to an avoidant attachment style. Or if we were feeling more cynical we could pin it down to a question of money. Michael Kierkegaard had left his son an inheritance. This inheritance was enough to support Kierkegaard alone but not a wife and kids. And so it may have been then that Kierkegaard's need for freedom and his writing aspirations tipped the scales towards going solo. The Either/Or may have been between the life of a writer and the life of a family man.

We don't know the cause. But the combination of this failed engagement and death's shadow proved to be a powerful cocktail for creativity.

The First Authorship

This first stage of Kierkegaard's writing career saw the Dane write sixteen books in three years. This phase ended with the book Concluding Unscientific Postscript in 1846, just over two months shy of his 34th birthday.

The essence of this phase is best illustrated by Kierkegaard's stages of life. This First Authorship explores three different value systems — three ways of being. Kierkegaard calls them the Aesthetic, the Ethical and the Religious stages.

The Aesthetic stage

The Aesthetic stage is the first of Kierkegaard's three Stages on Life's Way. The Aesthetic individual is one of the quintessential types of modernity. And it is probably more recognisable to us today than it was in Kierkegaard's time.

The Aesthetic stage is associated with the nihilism of hedonism. If this is all there is then we'd best be making the most of it. This isn't just the sensual hedonism of a Don Juan but the intellectual and cultural hedonism of the dandy or the bohemian.

There is an intellectual distance to the Aesthetic way of being. And this , as Kierkegaard tells us in Either/Or, is because for the Aesthete, "boredom is the root of all evil". The motivation of the Aesthete is not a positive moving-towards pleasure. It's a negative moving-away from boredom.

The life of the Aesthete is one distraction after another — another exhibition, another movie, another party, another rave. Whatever it is that keeps things moving. Ralph Waldo Emerson once wrote that when "skating over thin ice, our safety is in our speed".

This person has not yet committed to life. They value possibility over actual reality. They use irony, sarcasm and scepticism to keep life at a distance. It is a fundamentally egotistical way of being. By filling life with distraction — and keeping an ironic distance even from these distractions — the Aesthetic individual keeps life at bay.

The Ethical Stage

The Ethical is the second stage in Kierkegaard's threefold Stages on Life's Way. The self-centring Aesthetical stage of being gives way to the Ethical. This new stage connects into society. In Either/Or Kierkegaard uses marriage as the archetypal idea of this Ethical stage. Marriage demands that we relate to another individual in an open, intimate and honest way. And it also demands commitment. We have to enter into the world. No more staying aloof in the space of infinite opportunity. Marriage is a definitive step into life.

This is emblematic of the Ethical stage in general which is a call for us to enter into the world. The word Ethical in Kierkegaard is connected to Hegel's idea of Sittlichkeit. These are the traditional morals of the society — basically the social norms. To be Ethical is to be good; it means following society's tablets of good and evil.

These social norms justify our actions within the society. The measure of an action in the Ethical stage is how well it conforms to this tablet of values. These values are easily communicated and offer us clear ways of deciding whether an act is right or wrong.

The Ethical individual sees the Aesthetical life as selfish. The Aesthetical individual fails to acknowledge their social debt and their communal existence. They are living in a narcissistic fantasy land rather than living in the real world.

Nowhere is the Ethical ideal more unmistakable than in the advice of Jordan Peterson. He tells us to make our bed, to pick up a heavy burden, to carry our cross. Peterson's brand of self-help is a bridge between the Aesthetical and the Ethical.

Thousands and thousands of people who have been shunted by the brunt of life's meaningless and absurdity have found a new lease on life, a new tablet of values thanks to Jordan Peterson. In more ways than one, Peterson is a Kierkegaard for the 21st century.

The psychologist Peterson (in stark contrast to the culture warrior Peterson) encourages people to become responsible. He encourages them to take steps to improve their life and the lives of those around them. In short he encourages them to enter the Ethical Stage.

The Religious Stage

The final stage on Kierkegaard's hierarchy is the Religious stage. The best way of illustrating this stage is the Biblical example of Abraham and Isaac which Kierkegaard explores in-depth in his second masterpiece Fear and Trembling.

For Kierkegaard, being religious is not about joining a local congregation. Faith is a central element of Kierkegaard's thought. It is something we must live. The Bible was not the last word on faith. It's not something that's all worked out for us and we can set aside — that's the prejudice for reason and logic speaking. Kierkegaard says that every individual must do the work of faith for themselves. And not just once but again and again throughout their life.

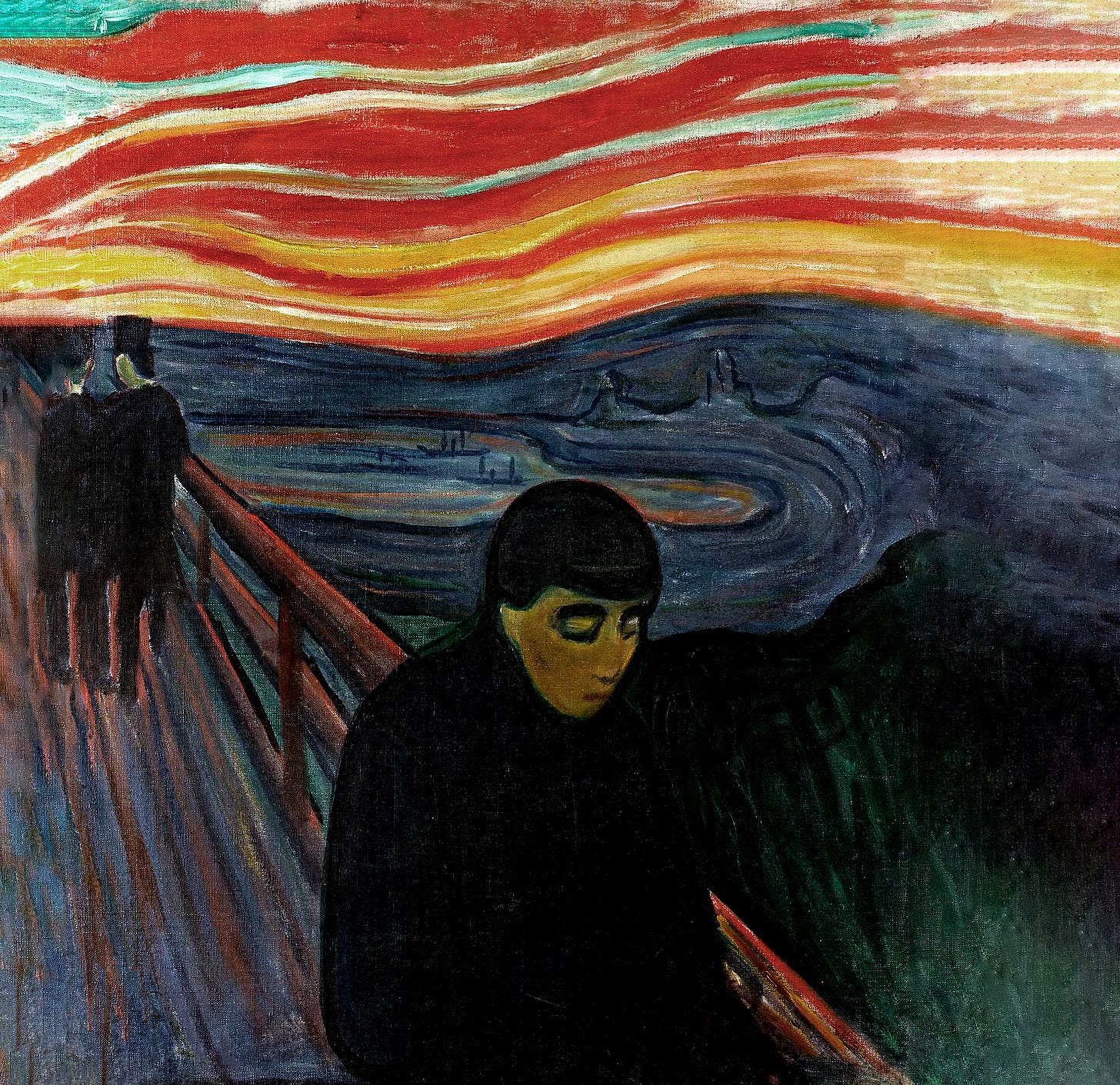

Faith is a choice we make as individuals and it is an excruciating choice. This choice is a massive burden of responsibility. On this choice hangs the individual's eternal salvation or damnation. And this is where Kierkegaard talks about his famous idea of Anxiety.

Anxiety is the awareness of the titanic magnitude of this choice of faith. It's a double-sided emotion. On the one hand you have the dreadful responsibility of choosing for eternity; on the flip side you have the exhilarating freedom of choosing for yourself. This choice happens in time — in a single moment. This moment is where time and eternity intersect as the individual through the choice creates a self that will be judged for eternity.

The Religious stage is beyond the Ethical stage. It transcends the Ethical stage. What we see in the story of Abraham is that faith requires us to go beyond the ethical and go straight to the source — to God. God for Kierkegaard is the ultimate source of ethics. And so when it comes down to deciding what is good and what is evil God has the final word.

And if he so chooses, God can suspend the ethical. This is what happens in the story of Abraham. God without any explanation, asks Abraham to kill his son Isaac. It's an impossible, horrible choice for a father. It is also, as Kierkegaard tells us, an inexcusable action from the point of view of ethics and the Ethical stage. There is no sensible justification for Abraham's action.

Now the obvious question is how do you know the voice in your head is God? How do you know you aren't another deluded nutcase killing their child because of some voices in their head? Because there is no rational explanation that can justify faith, Kierkegaard says we cannot know. We must take a "leap of faith". And that is why the title of the book on Abraham is Fear and Trembling. Because this is exactly what we are going to be feeling in a moment of faith. It is a cataclysmic crisis and this is the impossible choice that Kierkegaard is speaking to.

God cannot be held accountable to logic. The path of faith is antagonistic to the path of reason. They do not point the same way as Hegel claimed. They cannot be synthesised. We must choose. Kierkegaard says that we cannot believe by virtue of reason; the only way to believe is by virtue of the absurd. The belief of faith is an affront to reason.

Looking at the progression of the stages we can see a clear evolution. The Aesthetical stage focuses on the individual. The Ethical stage focuses on the community. And finally the Religious stage focuses on God. Each layer is nested in the greater reality of the next stage. We are connecting with higher and higher spheres in the hierarchy of Being.

Second Authorship

Kierkegaard had always intended to become a pastor after finishing his First Authorship. With the writing done he could knuckle down to the real work of his religious life.

But for some bizarre reason he picked a fight with a Copenhagen newspaper. Its name was "The Corsair" and it was famous for literary satire. Kierkegaard insulted the reputation of the paper and dared them to satirise him. And satirise him they did. For the next year Kierkegaard was the subject of vicious ridicule. They didn't go after the works but after the man portraying him as the centre of the world, as a hunched man and this hunched figure on a woman's back presumably Regine Olsen with a stick in his hand.

This attack devastated Kierkegaard. Wherever he went he was ruthlessly mocked. He gave up on his beloved walks through the city streets where he used to talk with people from all walks of life.

Because of all this, Kierkegaard postponed his quiet religious life a little longer and renewed his creative efforts. The attack by The Corsair was the impetus behind the Second Authorship as Regine Olsen and his father's curse had driven the first.

This Second Authorship dropped the satire and parody (though not the pseudonyms). And with it Kierkegaard focused on the creation of positive Christian discourses.

Kierkegaard wrote the works of his Second Authorship between 1846 and 1855. It was different from the First Authorship in many ways. Unlike the first phase of his work, the contours of this second stage were not mapped out in advance. It was a far less prodigious phase. In two of these years 1852 and 1853 Kierkegaard produced nothing at all.

The shadow of The Corsair affair is everywhere in these later works. The isolated personal faith of the individual was the First Authorship's centrepiece. But with this new phase Kierkegaard is thinking of the relationship between the true individual and the broader society. And he is also considering the nature of this broader society.

It began with a review of a novel called "The Two Ages". Kierkegaard used this review to critique the Modern age and its steamrolling of the individual. This "sensible age, devoid of passion" was creating an indifferent and abstract public he called "The Crowd".

Following this review was Works of Love. This book highlights the distinction between two Greek words for love: eros and agape. Eros or desire is a selfish form of love. Even if it isn't self-centred it is still directed at an exclusionary We. This "We" is the collection of people we have a personal inclination towards whether they are lovers, friends or family.

In contrast to this selfish love there is agape. This form of love isn't an inclination but a duty. It's not a preferential love of the people we are fond of but a universal love. It is the love of the neighbour regardless of who they are. This is the love that Christ exemplified in the Gospels. This love is a spiritual duty rather than a psychological inclination. And it can only come to be as a gift from God rather than from the attraction between human beings.

Sickness Unto Death approaches the same theme of the individual and the society from a different angle. This masterpiece of the Second Authorship is about Despair. Despair is the opposite of faith. It is when we are faced with the Anxious choice and choose wrong. It's choosing an inauthentic life rather than the life of the self (a theme that Jean-Paul Sartre picks up a century later with his idea of "Bad Faith"). Despair is the way of those who gain the world and lose their soul. Kierkegaard says the people who give in to despair "pawn themselves to the world" and he writes that:

"if you have lived in despair, then whatever else you won or lost, for you everything is lost, eternity does not acknowledge you"

The Kierkegaard of the Second Authorship sounds more and more like an Old Testament prophet. Like these ancient prophets he tries to call people back to true faith. He criticises the established religion as having lost its way. He warns the people about the wickedness of their society. He encourages them to align their lives with God and to change their ways.

From the review of The Two Ages and Works of Love to Sickness Unto Death and Practice of Christianity, Kierkegaard's intensity gears up.

This increasingly sharp criticism reaches a shrill peak in the last year of Kierkegaard's life. In this final phase Kierkegaard sets aside his elaborate method of Indirect Communication. And with the gloves off his attack on the Church and on Christendom reaches a fever pitch.

One of the bones Kierkegaard had to pick was political. He attacked the Church for being too connected to the State. He argued that this was creating perverse incentives that had nothing to do with being Christian in the Kierkegaardian sense.

On the religious side, Kierkegaard had many things to say. He believed that the popular conception of Christianity demanded too little of its adherents. He argued that congregations keep individuals like children since the individuals were disinclined to take initiative for their own relationship to God.

This soft Christianity clashed with Kierkegaard's Old Testament prophet vibe. He wanted a more "offensive" Christianity. He wanted to address "the problem of becoming a Christian" head-on. This task of the individual stood in stark contrast to the "monstrous illusion we call Christendom". Kierkegaard painted himself as a Christian missionary in Christendom.

And Christianity for the Existentialist Kierkegaard had always been "the individual, here, the single individual". Christianity was being reduced to a fashionable tradition that the herd dipped into once a week. This stood in stark contrast to the Herculean struggle with eternity at stake in Kierkegaard's Christianity.

This last phase of Kierkegaard's work was published in various newspapers and a series of his own self-published pamphlets called The Moment. Before publishing the tenth issue of this pamphlet, Kierkegaard collapsed in the street. A few days later he was in hospital where just over a month later on the 11th of November 1855 he died from a form of tuberculosis.

I just wanted to drop by and thank you for writing such a cogent piece on Kierkegaard. As someone who has a particular affinity for Albert Camus, I appreciate anyone's writing that tackles the Kierkegaardian/Camusian tradition within philosophy.

I learned a ton about Kierkegaard, which now has me pulling his work off my shelves. Thanks again, and I hope you continue to create content on here. Perhaps our paths will connect again in the future.