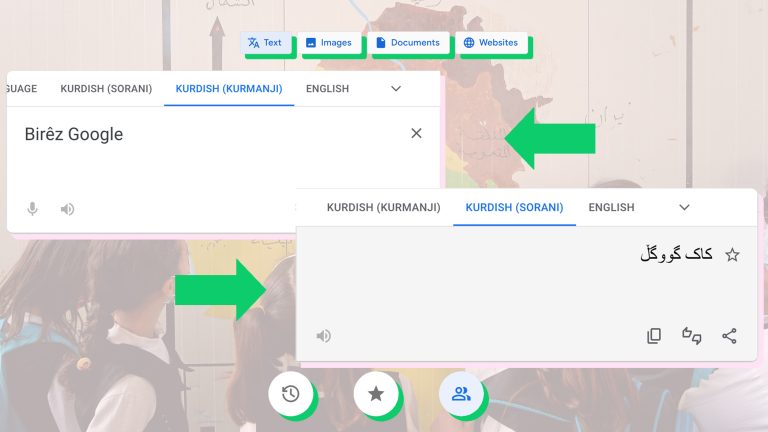

When Google learned to speak Sorani Kurdish, the company announced it without much fanfare. The Translate team shared the news in a brief blog post last May, revealing Sorani alongside 23 other languages like Twi from Ghana and Dogri from northern India. The post highlighted the new “zero-shot machine translation” system, as well as “the many native speakers, professors and linguists who worked with us.”

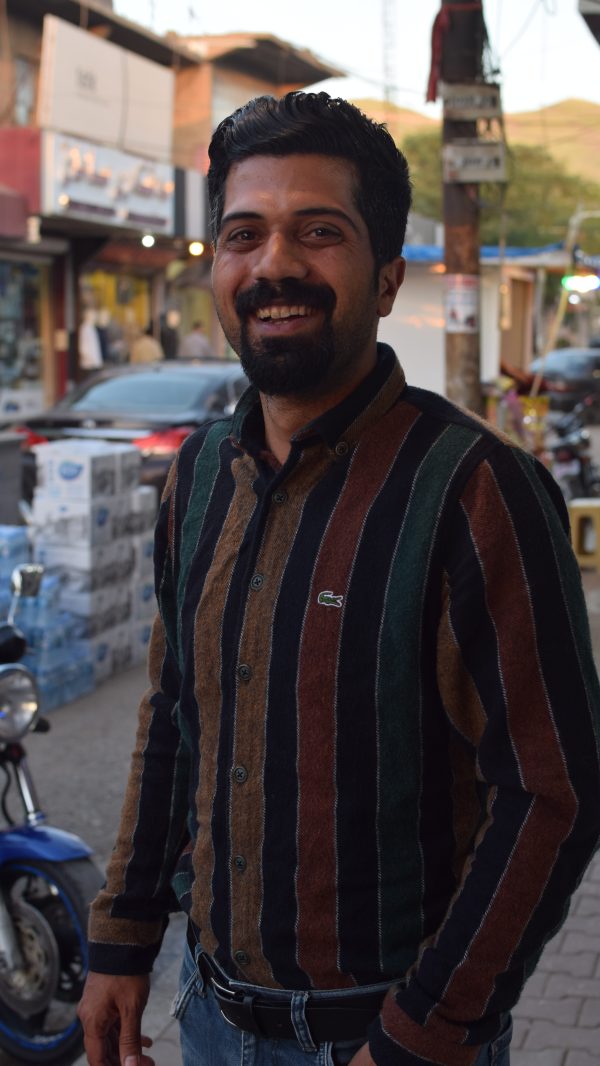

In the case of Sorani Kurdish, much of that work came down to one person: a 31-year-old from Halabja named Bokan Hassan, or Bokan Jaff. A soft-spoken man, he graduated from the University of Sulaimani in 2014 with a degree in English. But he struggled to find work after graduation, which led him to a series of piecemeal translation jobs. Neighbors would often come to his house for translation help, noticing that their own language was not included in most automated translation platforms.

“Sometimes they said, ‘Why Persian language? Why Arabic language? Why English language? Why French? Why Spanish?’” Jaff told Rest of World, speaking from a library in his hometown. “‘All of them can be translated … why Kurdish Sorani is not?’”

“I didn’t have a response for them. That’s why I tried to work,” he said. His home city of Halabja, located near the Iranian border with Iraq, is the site of one of the world’s most horrific chemical attacks. On March 16, 1988, Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist forces dropped chemical agents on the city as part of a genocidal campaign against the Kurds, killing around 5,000 civilians. Jaff’s older sister died in the attack and his father suffered lasting injuries. It is a particularly heinous example of the oppression faced by Kurds, who constitute the world’s largest nation without a state of their own.

For years, Jaff tried to find ways to get in touch with Google to advocate for Sorani to be added to its translation service. He finally made a connection in 2019 through an Argentine friend he met online. The friend was already volunteering on Google’s Crowdsource project through the company’s office in his home country. He told his colleagues about Jaff, whom they referred to a team working on languages.

Soon, Jaff was serving as a link between engineers at the U.S.-based tech giant and a vibrant community of language enthusiasts in Kurdistan. They spent countless hours translating words from Sorani into other languages, and verifying the translations of others on Google Crowdsource, eventually creating a beta version of the Translate platform. Jaff coordinated with the engineers to fix Sorani-specific language problems as they were encountered, and encouraged local Kurds to get involved. Without their work, it is unlikely that Google would have added Sorani to its translation platform.

Google Translate is not fully automated; it requires significant human assistance to learn a new language. The process begins with its system scraping the web for data to recognize languages and learn patterns — but the product isn’t ready for public use until those learned patterns are assessed by native speakers of the language. Google uses thousands of paid raters across the world to ensure the quality of its other products as well, including to refine its search engine results. Raters can be paid as little as $10 an hour.

Former Google engineer Keith Stevens, who worked on the Sorani Kurdish project with Jaff, described the volunteer work as particularly crucial for languages without a large population of native speakers. “If we have a lot of users … who are evaluating things for us, we can use that as a proxy for what a paid rater can do and that would give us a signal that, yes, this model is good enough and it’s safe enough to launch,” Stevens told Rest of World.

For some languages, particularly those with fewer living speakers, it can be a challenge to mobilize enough people to ensure that the service is translating long, complex sentences with consistent accuracy. But that community was already in place for Sorani, painstakingly built by Jaff even before he made contact with Google.

Spoken by an estimated 8 million people, Sorani (or Central Kurdish) is one of Iraq’s two official languages, along with Arabic, and is predominantly used in the semi-autonomous Kurdistan Region in the north. The language is also widely spoken in the Kurdish areas of western Iran, but is actively suppressed for official purposes by Tehran. Unlike Kurmanji (or Northern Kurdish), Sorani uses a script similar to Arabic, which makes it particularly difficult to process with algorithms trained on the Latin alphabet. For this practical reason, Kurmanji was launched on Google Translate much earlier, in February 2016. Once the beta version of Sorani was ready in May 2021, Jaff sent it out to members of the Google Crowdsource Facebook group that he manages. “I said, ‘Please, those who know English language send a message to me.’ About 5,000 users sent a message,” he said.

8 million The estimated number of people who speak Sorani.

Awadan Othman Ali, who works in a shop in Halabja and learned English in school, contributed hours of translations during the year-long beta testing phase. She had met Jaff years earlier as part of a local youth group, and knew that he was working on the project.

“I told him, ‘I love translation. Can I participate?’” Ali told Rest of World, adding that she focused on content she knew well in order to avoid mistakes. “I skipped the [sentences] that were about scientific or medical things because I didn’t know much.”

Today, Halabja still suffers from underdevelopment. Youth unemployment is high and many people hope to migrate to Europe in search of better opportunities. They are proud of their Kurdish ethnicity and language, but know that building better connections with the world beyond their mountain home is part of the future. When Google finally launched support for Sorani Kurdish, the reaction in Halabja was joyous, if a bit overwhelming, Jaff said.

Journalists from local media outlets clamored for interviews and politicians requested meetings to praise him for his work. He said he was warmly congratulated by diplomats at the U.S. consulate in Erbil, but it was the reaction from ordinary people that meant the most to him. People still stop him in the bazaar asking for selfies with “Mr. Google.” Car mechanics and dentists offered him free services, which he politely declined.

“Society pushed me to do my project, that’s why I worked hard.”

“They told me, ‘You help us. We will help you.’ I didn’t do it for this, but they know what I did,” Jaff said. “Society pushed me to do my project, that’s why I worked hard.”

Stevens attributed the success of the project to Jaff and the community of Sorani translators. Google engineers, he said, “wrote some code and made a website with a product and we took some data and shoved it inside of a magical box … but it’s really community members that made sure that the data was really accurate.”

That success came with some bitterness. The new Sorani translation service was widely available, but entirely owned by Google’s parent, Alphabet. The company, worth $1.35 trillion, hadn’t paid Jaff and his friends for their work.

“Google supported [us], but not in a financial way,” Jaff said. “I hope that Google company thinks about those who are working tirelessly to promote their company because they depend on the voluntary people.”

Stevens, who has since left Google, also acknowledged the company could do more to serve the communities from which it benefits.

“We ideally should publish [the data] with some open permissive license, where the community could do whatever research they want with it, so it’s not necessarily totally owned by Google. It’s not hidden in some dark vault,” Stevens said, adding that making the models open-source would be even better.

Google did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

While the translations for Sorani are generally well-regarded, there are still a few bugs to work out. In one particularly sensitive bug, Translate will occasionally confuse the Kurdistan Democratic Party, one of the ruling parties of Iraqi Kurdistan, with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, a militant group fighting for Kurdish rights in Turkish Kurdistan. The two are fierce rivals within Kurdish nationalism.

“I told [Google] this one is very, very sensitive. Please kindly work on this,” Jaff said, adding that Kurdish authorities understand the error is not intentional.

Still, Jaff feels proud of his work. The Kurdish language is suppressed in many states where Kurds live, so he understands the value of maintaining a living and accessible database of the language. For many Kurds, keeping Kurdish alive is a form of self-protection.

“This library is very important to my nation, but it will fade away,” said Jaff, referring to the books surrounding him. “It is a time of technology. Now, Kurdish Sorani is a global language.”