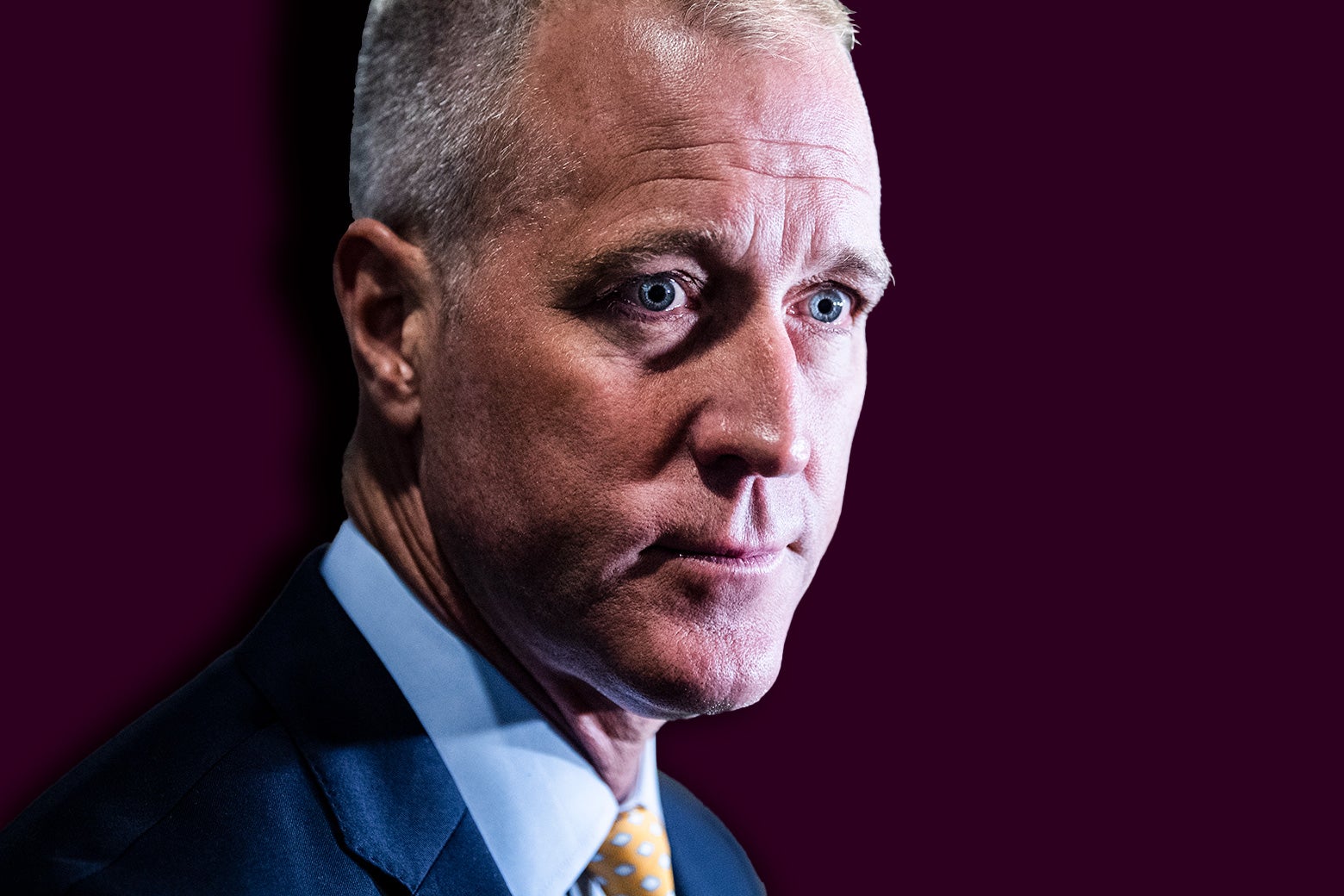

On an election night full of pleasant surprises for Democrats, things went surprisingly poorly for Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee chair Sean Patrick Maloney.

The New York Democrat may have been running the national party’s most important campaign arm—but he had arguably the worst individual performance of any politician in his home state. Not only did he lose his race, but congressional Democrats underperformed in New York more than in any other state in the country.

It’s a story that is at strange odds with the rest of the 2022 midterm results. In many states, House Democratic candidates are doing much better than expected—a turn of events that Maloney can share credit for as DCCC chair.

But in his home state of New York, four House seats were ceded to Republicans, including Maloney’s. He lost to Republican Mike Lawler in a district that in 2020 Biden carried by more than 10 points. Of the races that have been called, only Long Island Democrat Laura Gillen managed to lose in a more Biden-friendly district; she, unlike Maloney, is not a sitting member of Congress.

Maloney is also the first DCCC chair to lose reelection in 40 years. It remains possible that, even with all the unexpected House wins around the country, it could be his lost seat that delivers Republicans control of the House.

Some Democrats have scrambled to portray Maloney’s face plant in New York as an act of self-sacrifice, framing him as a politician who gave up his own race to help Democrats elsewhere. Maloney has said that others, including Kathy Hochul and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, should share the blame for his downfall. But in interviews, local liberal and conservative political strategists describe a candidate who alienated Democratic grassroots groups and made no effort to court their help, even after he chose to run in a district, New York’s 17th, where he had built up little goodwill and spent precious little time. “Instead of working with NY-17’s strong Indivisible network and other grassroots groups to build a ground game, Maloney ignored and antagonized the local base,” said Dani Negrete, national political director of Indivisible, a nationwide grassroots group with thousands of local affiliates.

In the weeks before Election Day, Maloney set off on a Europe trip, where he hung out on a balcony overlooking the Seine, and turned up in London, Paris, and Geneva, often alongside congressman Adam Schiff, for gatherings billed as DCCC fundraising events. (The DCCC said in a statement that its total efforts in Europe, of which Maloney’s trip was part, raised $1 million.)

Prior to that October sojourn, Maloney’s 7,000-square-foot Cold Spring estate, the residence that was just barely drawn into the 17th Congressional District earlier this year, was listed as a vacation rental on Expedia with the disclaimer “Minimum 2 month rental from July 1–August 31.” (The Maloney campaign said the house was not rented and that the listing was a “ghost post” left over from a previous time.)

While Maloney was across the pond, the Republican National Campaign Committee and Congressional Leadership Fund, Republicans’ two largest campaign arms, were pouring big money into his race, over $10 million in independent expenditures. While attack ads blanketed the airwaves, Lawler and his team hit the ground, shoring up support. Internal polling began to reflect his growing advantage. Maloney dismissed the threat in an interview with ABC News, stating repeatedly that Republicans were “lighting [money] on fire.”

Outwardly, Maloney was projecting confidence, but clearly he didn’t feel it. Just a couple of days after his ABC spot, a pop-up super PAC closely aligned with the Democratic Party, called VoteVets PAC, announced a $1.2 million ad buy on Maloney’s behalf. Maloney is not a veteran. But Nancy Pelosi’s super PAC, House Majority PAC, was the group’s top donor in September. Maloney also began raking in money from his Democratic colleagues. In late October, when the 24-hour reporting window for contributions of $1,000 or more began, Maloney banked more contributions from Democratic members and leadership PACs than any other Democrat.

Across the major Democratic outside spending committees, Maloney sopped up more than $4 million in support, all of it coming at a time when the DCCC he chairs—as well as Pelosi’s House Majority PAC—was crying poor and cutting funding in extremely winnable races. He had pledged in August not to spend party resources on his own race. Just a few months later, he was siphoning critical dollars that could have gone to other contests, including Oregon’s 5th, where the DCCC and House Majority PAC both cut bait on Jamie McLeod-Skinner, a Democrat who, on Sunday, narrowly lost to her Republican opponent.

“Congressman Maloney worked tirelessly and never wavered from his commitment to the people of the Hudson Valley,” said Mia Ehrenberg, a spokesperson for Rep. Maloney, when asked for comment. “As part of his DCCC role, Chairman Maloney raised millions for candidates to stop MAGA Republicans from materializing a ‘red wave.’ ”

Snubbing the Grassroots

In a midterm election where a major enthusiasm gap (and low approval ratings for the president) looked likely to benefit Republicans, the support of grassroots groups was important for Democrats to gin up voter turnout.

This would have been especially true for Maloney, given the demands of his DCCC post.

But according to conversations with many local grassroots organizations, Maloney made no effort to secure their support. The Working Families Party, which sports a massive grassroots infrastructure in New York and played a critical role in helping Gov. Kathy Hochul cross the finish line, endorsed Maloney and put him on its ballot line. Still, according to Meredith Wisner, chair of the Rockland County WFP chapter, Maloney’s people never got in touch. “We organized for his campaign, but didn’t organize with his campaign, because the campaign never reached out to us,” Wisner told me.

It wasn’t until Oct. 27, just 12 days before election day, that the Maloney campaign connected with Wisner at all, and that was only in response to an email that she sent them. “Did they expect me to reach out first? I guess they did, because that’s how it happened,” she told me. “Rockland Working Families is a chapter, we’re small, but we have a big mailing list.”

Other progressive strategists, including at Indivisible, which has 400 registered chapters in New York, also reported that Maloney made little to no effort to court progressive groups and their extensive grassroots network.

This is baffling on several levels.

Maloney’s entry into the new 17th District—where he technically lived according to the state’s redrawn maps, but which encompassed less than 30 percent of the district he had been previously representing—was nothing short of a disaster. The district had been represented by Mondaire Jones, a native son who grew up in Rockland County and who had already established a national profile even as a freshman. Maloney vacated New York’s 18th District, a Biden+8 district, and jumped into the bluer 17th, which Biden won by more than 10 points, pushing Jones out in the process. (Forced to choose between a primary race against the powerful DCCC chair and an open district in Manhattan, NY-10, Jones chose to run in the latter. He finished third.)

Then, Maloney had a bruising primary against a well-liked state senator, Alessandra Biaggi. He won by a comfortable margin, but the race proved surprisingly bitter and, for some, made the bad taste from the Jones saga linger.

“When you run in a largely new district, it’s standard practice to quickly build partnerships with the local grassroots operations that will be your boots on the ground,” said Negrete, Indivisible’s national political director. “We heard from Indivisible activists in the district who were more mobilized by some state senate candidates with a better ground game, while the DCCC chair himself was likely more of a drag on the ticket.”

Maloney’s spokesperson, Ehrenberg, said in a statement: “From the day the primary was over, our campaign aggressively reached out to WFP, Biaggi supporters, and local progressive groups to bring the coalition together heading into November. We hosted a meet & greet, a unity rally, and did extensive outreach behind the scenes.”

Snubbing His New District

Maloney’s primary was a harbinger of his coming troubles. To beat Biaggi, a progressive, he accepted nearly half a million dollars in support from the Police Benevolent Association, the New York City police union, which put that money toward vicious attack ads that denounced the state senator as “a radical anti-police extremist” who “voted to release criminals without bail.” In the general, Lawler attacked Maloney using a similar tactic, portraying him as soft on crime.

But Maloney should have been worried about a larger hurdle to winning over his new district. Campaign strategists repeatedly mentioned that Maloney’s treatment of Jones—who grew up in the district that Maloney pushed him out of—was a serious issue for potential voters they talked to. “I was surprised at just how much people brought that up canvassing in the general,” said Wisner, of the Rockland County WFP. “Lower voter information folks, average voters, even they were kind of disgusted.”

She said that when activists were door-knocking, “people would say, ‘Isn’t he the guy that pushed Mondaire out of this district?’ Folks had a really tough time getting past that. And he didn’t do much work past saying, ‘Well, I live here.’ ”

Maloney was also regarded with suspicion by some environmental activist groups in the Hudson Valley, which have a strong political tradition dating back to community organizing efforts in the 1970s against General Electric’s pollution of the Hudson River. One such organization, Food and Water Watch, had previously locked horns with Maloney over a 2021 campaign to stop the expansion of a fracked gas power plant on the Hudson River.

Maloney was a vocal supporter of the plant, which put him at odds with Food and Water Watch, even as the group built a significant local footprint—and ultimately succeeded in blocking the power plant expansion. (Maloney’s stance also put him at odds with Jones when Jones first arrived in Congress; after Jones circulated a letter drumming up opposition to the plant’s expansion, his staff was reamed out by Maloney’s office, according to a former staffer.) Maloney made no attempt during election season to make nice with the group. “There were easy things he could have done,” said Alex Beauchamp, northeast region director of Food and Water Watch.

Next door, in the neighboring 18th District that Maloney vacated, the Democrat ran successfully on environmental issues, one of the few congressional victory stories for New York Democrats in the midterms. “The district Maloney was scared to run in was won by Rep. Pat Ryan, who has a sterling environmental record,” Beauchamp said. “It’s remarkable that that was a winning campaign right issue next door, in mostly his old district.”

There are plenty of reasons that New York Democrats had a tough midterms: They include New York Democratic chairman Jay Jacobs, a Republican-friendly gerrymander, and a lack of foresight on the part of disgraced former governor Andrew Cuomo. Maloney himself had plenty of establishment backing: Former President Bill Clinton campaigned for him, and he drew endorsements from the Sierra Club, the League of Conservation Voters of New York, and the powerful Democratic Majority for Israel. This, along with the Democratic House wins across the country that many have interpreted as evidence of Maloney’s tactical know-how, could be spun to advance the narrative that Maloney lost because of forces outside his control.

But the fact remains that the DCCC chair didn’t cultivate support in his own district and was forced, at the end of his campaign, to absorb millions of dollars of limited Democratic campaign money that could have gone elsewhere. His loss not only cost Democrats the eminently winnable 17th District—it almost cost them the district he vacated as well. Will it now cost them the House?

In a phone call, Bill O’Reilly, the communication director of New York 17th’s incoming Republican House member, Lawler, reflected on the win. “I feel bad saying it because he’s been so gracious,” he said, of Maloney. “But it really was just an ‘outworked’ situation. He wasn’t around, and we just outworked him.”