Palestinian author and editor Atef Abu Saif—who since 2019 has also served as the Palestinian Authority’s minister of culture in the West Bank—was visiting the Gaza Strip when Hamas launched its Oct. 7 attack, and when Israel then launched its military response on the territory. Saif took shelter in the Jabalia refugee camp in northern Gaza, where he began writing daily diary entries documenting his experiences with friends and family there. Surviving airstrikes on the camp, he recently fled Jabalia to the south. He spent two days in Khan Younis, before moving to Rafah, where he has spent the past week.* Slate is publishing three of his diary entries from the days ahead of his move to the south, the first of which is below.

Saturday, 18 November (Day 43)

Thousands have been forced to leave these homes this morning after renewed attacks targeted the peripheries of Jabalia camp overnight. From 9:30 p.m. to 6:30 a.m., the air raids never stopped coming, from the west, the north, and the east. Hell was poured on Jabalia. Hundreds of buildings were destroyed. When the sun rose, those who survived simply had to run with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Most of them headed toward the center of the camp. The schools are full, everyone knows, but they have nowhere else to go. The majority of this great flood of people came into the camp from areas adjacent to Beit Lahia and Beir Naja.

I didn’t sleep all night. I had decided to spend the night at my sister Asmaa’s place in the Falouja neighborhood. Yesterday was one of those days when I needed a change: I cut my hair and I shaved my beard. This has been the longest I’ve ever gone without shaving. I almost forgot what I look like without a beard. I’m now a new man. I told myself this would change my mood and give me renewed energy. God knows I needed it. Moments of silence and depression had started to creep into my day. It’s happening to most of us. No one was prepared for such a long war. When people compare this war with the 2014 one, they say that this is a real war, whereas 2014 was just a massive onslaught. Back then, we had truces and temporary cease-fires now and then through the 51 days. In this war, the idea of a truce seems more complicated than the war itself. Two nights before, when I slept in the school shelter, everyone in the tents was shouting; men were singing prayers to God, women were saying blessings. Everybody was celebrating the rumor that there might be a truce that night. The celebration lasted for half an hour before they realized this was just a piece of wishful thinking someone had spread around to pacify them. Now weֹ’re on Day 43, and the talk about a truce needs its own truce. No one believes any mention of it any longer, least of all on the news.

I look at myself in the mirror. “This is Atef,” I say. “The one you barely recognize, the one whose face war has etched its tiniest details into.” I look thin, drawn. Last night I told my brother Mohammed that we had to stay at Asmaa’s place in Falouja. We can pass the evening talking with her and her husband and playing with her five little daughters. Asmaa has set up three camp beds for us in the living room, in between her two blue sofas. We talked. We played. We listened to news on the radio. Then we had to sleep.

When the attacks start, the building is completely dark. The light from the explosions washes into the living room through the windows, making all the pictures and mirrors sparkle. Any Gazan will teach you to listen for the explosion after the flash. Next comes the sound of debris raining down; we could hear it on all sides of the house, in the narrow alleyways behind and beside us, and in the main street out front. I insist it’s too dangerous to sleep in the living room, so we drag all our mattresses to the innermost part of the flat, a tiny corridor space next to the kitchen. The 10 of us lie there, waiting for sunrise. We pray for God to bring this night to an end. I try counting the missiles and explosions. I get up to 154, then I stop. There is one particular type of missile that hisses before it explodes. Mohammed says it is a new one. He has been in Gaza these past four years; he knows better than me.

In the Tal Azzatar schoolֹ’s shelter, a missile kills dozens and injures hundreds more.

At 5:30 a.m., we all start to get up. I look out the window at the school shelter across the street, where I slept two nights before. People are all crammed into the classrooms on the first floor, having been forced to leave the tents during the night. It’s dangerous these days to stand too long at the window; snipers might shoot you for the fun of it, so I don’t look for too long.

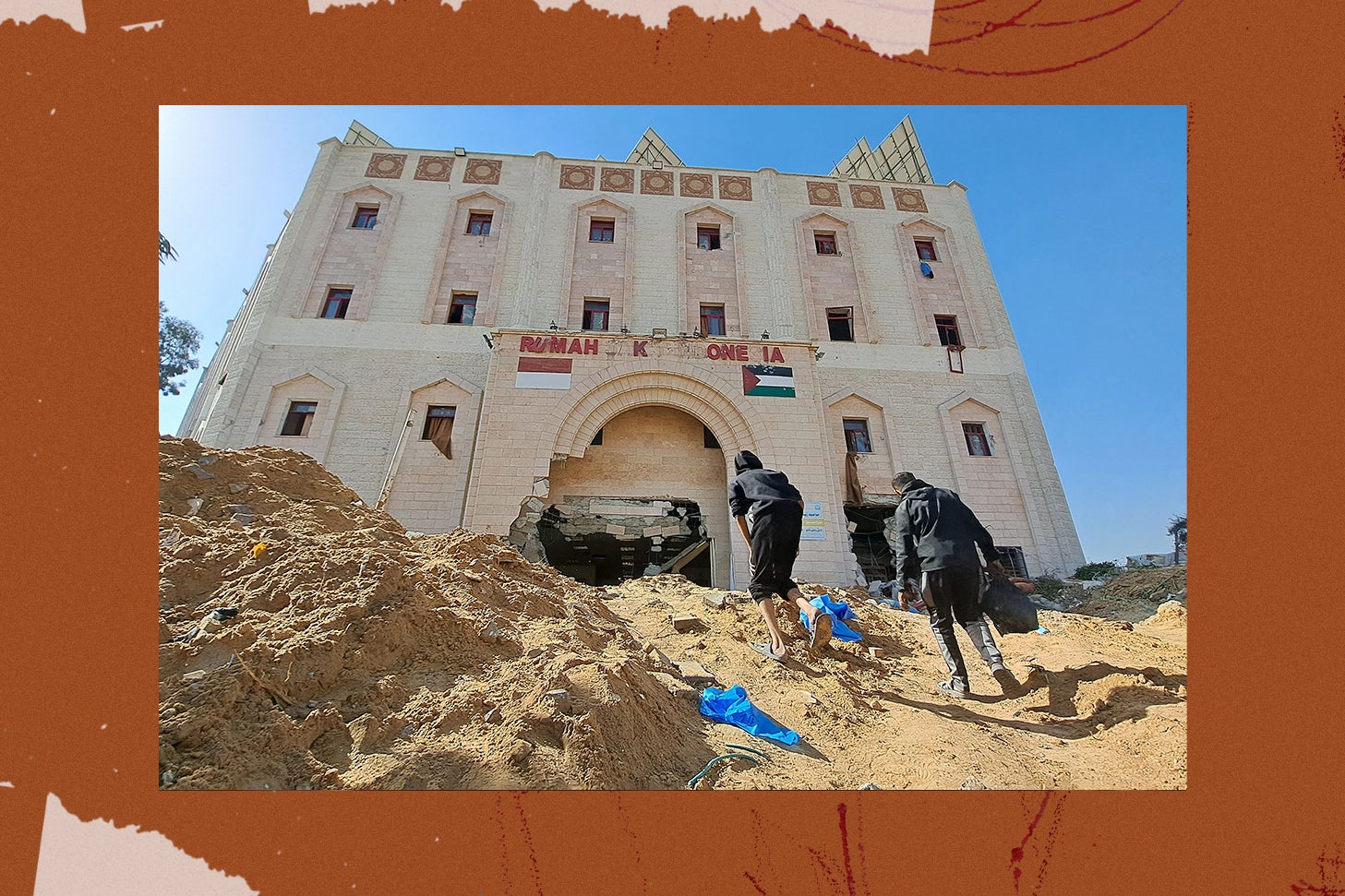

Yesterday evening I went to visit a friend, Mahmoud Mohaisen, who’s been wounded and getting treatment in the Indonesian Hospital. The place was very crowded, of course, and bullet holes and missile craters could be seen in every corridor. Many things there were identical to what al-Shifa [hospital] had been like: people living in tents, temporary field hospital wards at the front, erected out of canvas, corridors full of displaced families, insufficient numbers of beds, with injured patients being treated on the ground.

This morning, over in al-Shifa, the Israelis gave everyone inside one hour to leave, be they patients, doctors, nurses, or displaced people, as they intended to make their final push into parts of the hospital that hadn’t been conquered yet. No one was to remain inside. According to reports, Israeli soldiers were taking bodies out of the hospital’s mass grave, presumably thinking something else was being hidden down in that pit.

The Indonesian Hospital sits at the top of a small hill and, with its Islamic architecture, feels a world away from the carnage of al-Shifa. That said, the place is barely functioning.

At 8 p.m. I turned in, sleeping soundly for four hours. Mohammed and my son Yasser likewise. No dreams, no nightmares, no waking up every five minutes to count the explosions or wonder where they were. Often, you need to forget the world around you and just turn off.

This morning, I walk around the camp to take stock of the newly attacked areas. The more I walk, the more I see of last night’s damage. Here and there, I realize it’s old damage from several days ago; it’s only new to me. Jabalia is disappearing, vanishing day by day. We are vanishing too. According to new statistics, more than 2 percent of the population of Gaza Strip is either killed, missing or injured, while 70 percent of us are homeless. [Editor’s note: The exact numbers are unclear, but CNN and the Washington Post have gathered similar statistics.]

Now the tanks are firing on the Fakhour schools, and early reports speak of around 200 dead. The attacks from north, east, and west of the camp are pushing those who remain south. It’s clear the path to safety is getting narrower and narrower.

Correction, Nov. 30, 2023: Due to an editing error, this article’s introduction originally misstated that the author had left Gaza through the Rafah border crossing into Egypt. He had not.