On Monday, the Supreme Court issued a bitterly divided 5–4 decision upholding all but one of Texas’ gerrymandered districts, ruling they were not drawn with impermissible racial bias. Justice Samuel Alito’s majority opinion reverses a lower court’s conclusion that Texas gerrymandered both congressional and state legislative districts in order to curb the power of minority voters. The ruling is a brutal blow to civil rights advocates, who amassed a vast record of evidence that Texas mapmakers diluted the votes of Hispanic residents.

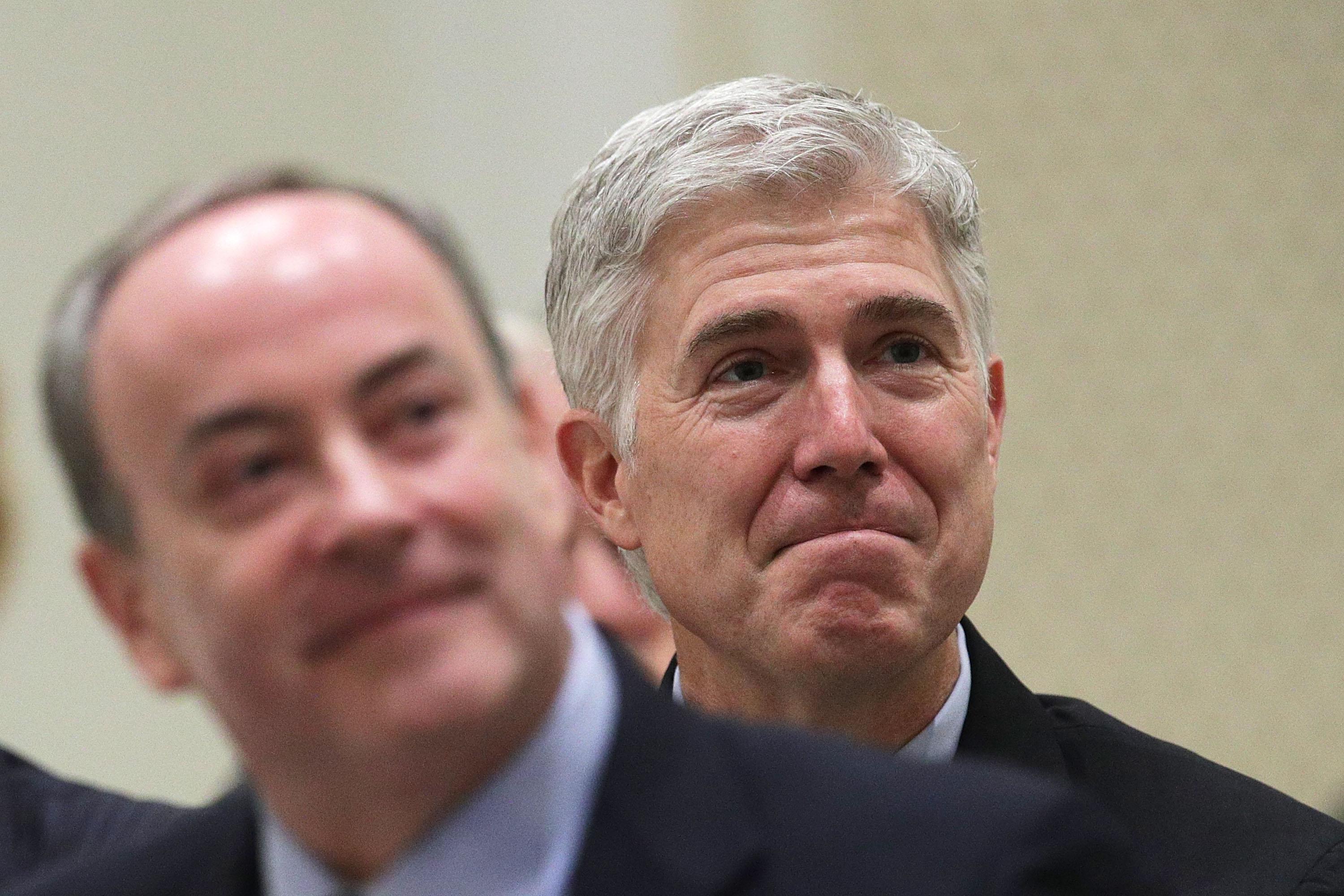

What may be most remarkable about Monday’s decision in Abbott v. Perez, however, is Justice Neil Gorsuch’s effort to position himself as a fierce opponent of the Voting Rights Act. The Supreme Court already gutted a central provision of the VRA in 2013’s Shelby County v. Holder. Now, in Perez, Gorsuch has joined Justice Clarence Thomas’ crusade to hobble the law even further by holding that it does not prohibit racial gerrymandering. Were the court to adopt Gorsuch’s interpretation, the VRA could never again be used to stop racist mapmakers from diluting minority votes.

The VRA was designed to enforce the 15th Amendment’s bar on racial voter suppression in several ways. Its most effective tool allowed the federal government to block suspect voting laws in states with long histories of racial discrimination—but SCOTUS disabled this provision in Shelby County. Luckily, a different part of the VRA, Section 2, forbids any “standard, practice, or procedure” that “results in the denial or abridgement” of the right to vote “on account of race or color.”

For decades, the Supreme Court has held that Section 2 outlaws gerrymanders that dilute the votes of minority citizens. This rule makes good sense, as these gerrymanders plainly constitute a “practice” or “procedure” that would “abridge” minorities’ right to vote. The court has explained that vote dilution occurs when mapmakers limit a minority group’s ability to translate its voting strength into voting power, drawing district lines to ensure that white voters can select its preferred candidate. Typically, mapmakers pack as many minority voters as possible into a few districts, then distribute the rest through majority-white districts. As a result, minorities are deprived of an equal opportunity to participate in the electoral system.

Perez revolves around this principle. In 2017, a federal district court ruled that Texas had, indeed, diluted minority votes in violation of the VRA. The court held that the state could have evenly spread Hispanic voters through a number of compact districts, giving them a real chance to elect their candidate of choice. Instead, Texas packed Latinos into a handful of bizarrely shaped districts, then distributed the rest throughout majority-white districts. As a result, most Latinos had no genuine opportunity to elect their preferred candidate—in effect, helping the mostly white Republican majority entrench its electoral power. It was, the court found, a textbook case of vote dilution.

Alito reversed the lower court’s decision, complaining that it had “disregarded the presumption of legislative good faith” and unfairly imputed racism to Texas’ mapmakers. In dissent, Justice Sonia Sotomayor accused the court of running interference for racists by “blind[ing] itself to the overwhelming factual record” to let Texas use maps that, “in design and effect, burden the rights of minority voters.” Alito, Sotomayor wrote, is “just flat wrong,” relying on “a selective reading” of the facts to ignore clear evidence of “racial discrimination.”

In a brief concurrence, Thomas explained that he would’ve gone further than Alito. Rather than reject the plaintiffs’ VRA claims, he wrote, the court should have overturned decades of precedent to hold that the VRA does not prohibit racial gerrymandering at all. Thomas has argued this point for years, often joined by Justice Antonin Scalia. On Monday, Gorsuch took up the mantle, conspicuously signing onto Thomas’ assertion that the VRA allows mapmakers to dilute minority votes.

It is difficult to overstate how devastating this theory would be if it ever gained majority support on the Supreme Court. In theory, the Equal Protection Clause also bars race-based vote dilution. But those claims are vastly more difficult to win because challengers must prove racist intent, not just racist impact. Since legislators today have found ways to enact racist laws without leaving behind smoking gun evidence of their racial motivation, proving intent has become an almost impossibly high bar under most circumstances. The Thomas/Gorsuch position, then, would give states a free pass to gerrymander away the voting power of minorities, so long as they dressed up their intentions with sufficient pretext.

Gorsuch is, in many ways, the central figure in Perez. In September 2017, he provided the fifth vote to preserve Texas’ racial gerrymander through the next elections. Now he has once again furnished the fifth vote to uphold virtually all of Texas’ racist map. And in the process, he has declared war on the VRA, inviting future challenges designed to sabotage the law’s ability to guard against racial vote dilution. Gorsuch has served on the court for justice over a year. But it is already apparent that the newest justice will be a staunch ally to lawmakers who wish to suppress the votes of minority Americans.