Numlock Sunday: Risk aversion and the most destructive trend in Hollywood

By Walt Hickey

Welcome to the Numlock Sunday edition.

Something a little new I wanted to try out today! Let me know what you think.

I wanted to kick off the summer box office season at the movies by talking to someone with a fun take on the current state of the cinema, at which point I realized, hey, I actually have a take about the current state of the cinema I’ve been meaning to air out. So, here we go!

This is going to run concurrently in the Numlock Awards newsletter as a wrap on the season, so do check that out if you’re interested. Lots of it is drawn from the reporting in my book, which you should check out if you have not yet.

Earlier this year I was doing a talk at Neuehouse with the author Jeff Yang about our books, when someone asked a question about the then-upcoming Oscars. I’m paraphrasing, but the question was effectively why should we still care about these things? Jeff’s book, The Golden Screen: The Movies That Made Asian America, came out the year after Michelle Yeoh became the first Asian person to win Best Actress.

But that long wait provokes some obvious questions about what is the point of an award show that I think most concede is inconsistent at identifying the best performances and films. I don’t need to recap this debate, as everyone who cares about — or conversely, doesn’t — has had it at one point or another.

My answer to this question sidestepped the important questions of how we measure and rate quality, why we give awards, what the point of this all is. I drew instead on the economic: the existing incentives are such that every marginal dollar in Hollywood ought to be invested in sequels, reboots, and established players. Oscar potential is one of the sole remaining arguments to make film without an obvious commercial angle.

The Oscars matter because almost every other incentive to fund provocative, original, and innovative work has dried up. It’s the last argument against risk aversion we’ve got. You don’t have to like ‘em, and you certainly don’t have to agree with ‘em, but they’re an oasis of motivation in an increasingly mercenary industry and we should be grateful they exist. I’m going to draw on reporting from my book, You Are What You Watch, to make this argument. Let’s dive in.

Risk Aversion

There is a perception that Hollywood is obsessed with making money above all else. This is only partially true. The only thing that Hollywood values more than making money is not losing money.

Nobody ever lost their job by greenlighting safe, reliable franchise films that doubled their budget and made a slight if reliable profit for the studio. Lots and lots of people have lost their jobs by greenlighting something weird that bombed. It’s a system that incentivizes an aversion to risk.

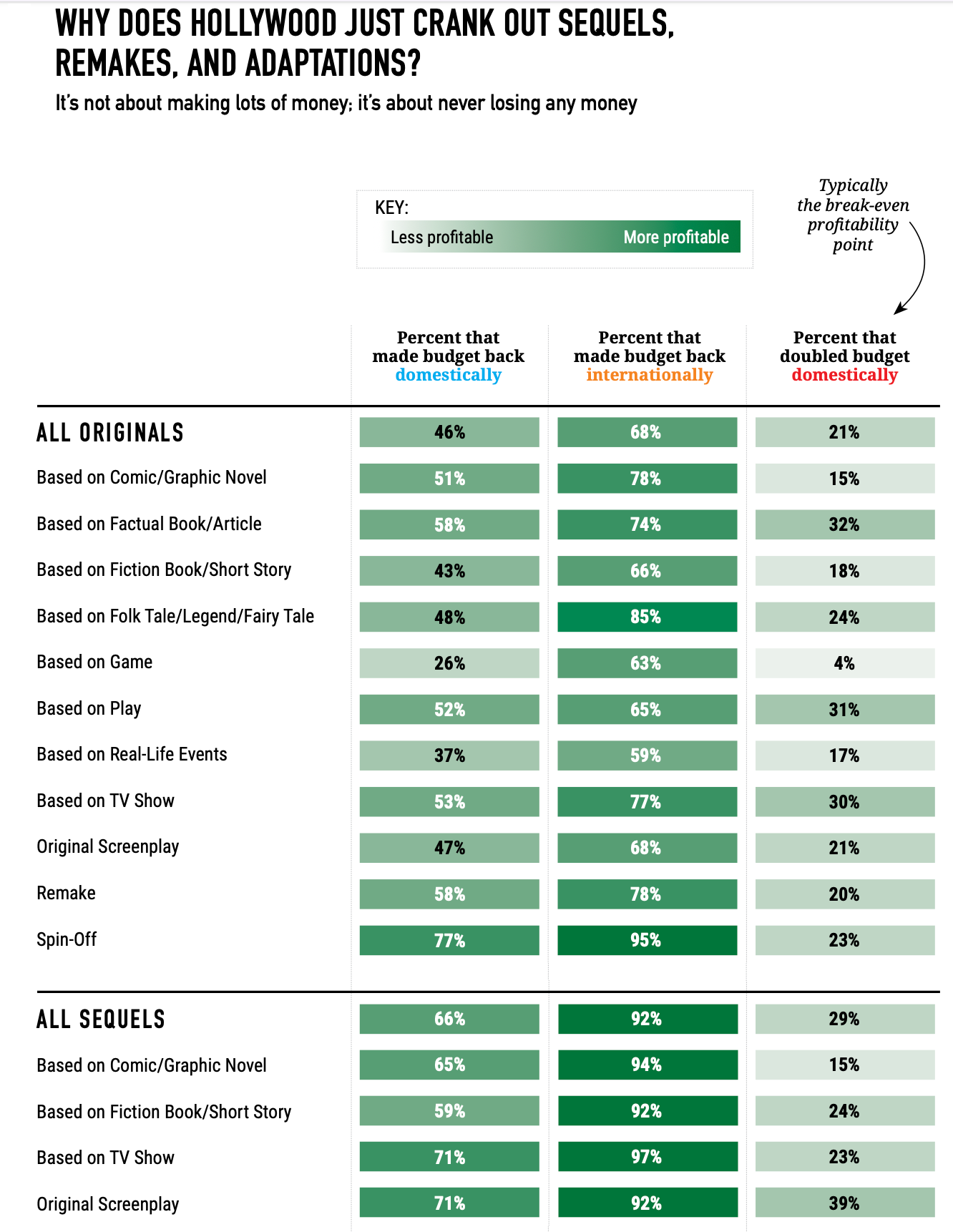

The data here is all pre-pandemic, and there have been some shifts (see: video games), but here’s the rate at which films reached certain thresholds of box office revenue given their budgets, and based on whether the films are new properties, sequels, or based on pre-existing work.

You can see it right there: 46 percent of films without a pre-existing franchise hook made their budget back domestically, compared to 66 percent of sequels. That figure reached 77 percent for spin-offs and 58 percent of remakes.

If you’re greenlighting movies, that math is pretty hard to argue with.

Every dollar you spend on an original concept is a riskier wager than every dollar you spend on a sequel or a reboot. This is a business, and Wall Street likes businesses where one dollar goes in, and one dollar and twenty five cents comes out. They don’t care for businesses where a dollar goes in, and the number that comes out is maybe 25 cents, sixty cents, eight dollars, one dollar, or ten cents.

As a result, the incentive structure in Hollywood has made it so that it’s financially difficult to get movies that are slight risks made.

What that’s done

Just take a look at the major releases for upcoming summer, which is supposed to kick off this weekend with The Fall Guy.

Originals: Back to Black (May 17), IF (May 17), Horizon: An American Saga (Part 1, June 18, Part 2, August 16), The Bikeriders (June 21), Borderlands (August 9), Trap (August 9)

Sequels, Reboots, or Franchises: Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (May 10), The Strangers: Chapter 1 (May 17), Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga (May 24), The Garfield Movie (May 24), Bad Boys: Ride or Die (June 7), Inside Out 2 (June 14), A Quiet Place: Day One (June 28), Despicable Me 4 (July 3), Beverly Hills Cop: Axel F (July 3), Maxxxine (July 5), Twisters (July 19), Deadpool & Wolverine (July 26), Alien: Romulus (August 16), The Crow (August 23), Beetlejuice Beetlejuice (September 6), Transformers One (September 20).

That’s not a lot of new ideas! I’m sure a lot of these movies are going to be really good. I, for one, am actually pretty bullish on this summer. But in terms of new visions, in terms of new ideas, what are we working with here?

Compare it to the summer of 2004, which had originals like The Day After Tomorrow, I, Robot, Troy, Van Helsing, Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story, The Village, Collateral, Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy, The Notebook, Napoleon Dynamite and The Terminal.

Or, if you really want to feel it, the summer of 1994, which had The Lion King, Forrest Gump, True Lies, The Flintstones, Clear and Present Danger, Speed, The Mask, Angels in the Outfield, and Natural Born Killers.

And this year, what even are those originals? A video game adaptation, an Amy Winehouse biopic, a John Krasinski-Ryan Reynolds movie, M. Night Shyamalan back again, all established brands. Two of those are projects by Kevin Costner, who self-financed it. Hell, Francis Ford Coppola spent an entire winery making Megalopolis, and nobody’s interested.

The point here is, these incentives to not lose money above all else have had real ramifications. In the commercially driven summer box office, there are not a whole lot of risks being taken, there’s not a whole lot of new blood being featured, and there’s not a whole lot of experiments being done, at least not on Hollywood’s dime.

The wildest, most original gambles are self-financed, because an auteur wanted to make a risky work and the only way to make that happen was by coughing up the change themselves.

Which brings us back to the Oscars.

What the Oscars are for

Going back to the question at hand, why should we still care about these things?

Well, the good news is that there is still a motivation for the moneymen to invest in speculative, challenging work, and that is because of the Oscars. It might be your lifetime ambition to win an Oscar, it might mean as little as a paperweight to you, but the Oscars are still a highly desirable industry award for the executives who control the money in Hollywood.

Even as the audience for the Oscars has slipped, even as their relevance has been debated, even as the composition of their voters has been scrutinized extensively, people who control the purse strings still really, really want this thing. People who work in movies, in front of the camera or behind it, still really want these things. Every Oscar night you see a little bit of that magic, from the speechlessness of Emma Stone when she won for Poor Things, or the triumph of Cord Jefferson when he won for American Fiction, or Christopher Nolan finally getting up there after decades for Oppenheimer.

Does Nolan get $100 million to make a movie about physics if the Oscars don’t exist? Does American Fiction get the room it needs to breathe as an auteur-driven film if its only possible measure of success is box office? Does Poor Things get a $35 million budget if not for the Oscars track record of Yorgos Lanthimos and Emma Stone? I think the answers are no. I think they’d find a way to exist, perhaps, but not at the level of creative control, and not at those budgets.

That’s what the Oscars are for. The distance between Wall Street and Hollywood has shrunk, industrial consolidation has meant that inconsistent returns are no longer viable. The Street wants a consistent ROI more than it wants a blockbuster quarter, and the industry is prepared to give it to them.

Risk aversion is dangerous. The risk of running out of new ideas, the risk of failing to lay the groundwork for the franchises of the future are real. This isn’t to say that all the risk-takers are gone — smaller studios like Neon and A24 have punched above their weight at the Oscars by having a stronger stomach for risk, and institutions like the Black List and the Nicholls Fellowship continue to give original scripts a boost in a risk-averse town — just that to understand why the industry is as it is, risk-aversion is the key thing.

And that the Oscars — stodgy they may be, flawed they may be, inconsistent they may be — are one of the rare institutions actually incentivizing risk-taking, and for that we’re all better off.

If you have anything you’d like to see in this Sunday special, shoot me an email. Comment below! Thanks for reading, and thanks so much for supporting Numlock.

Thank you so much for becoming a paid subscriber!