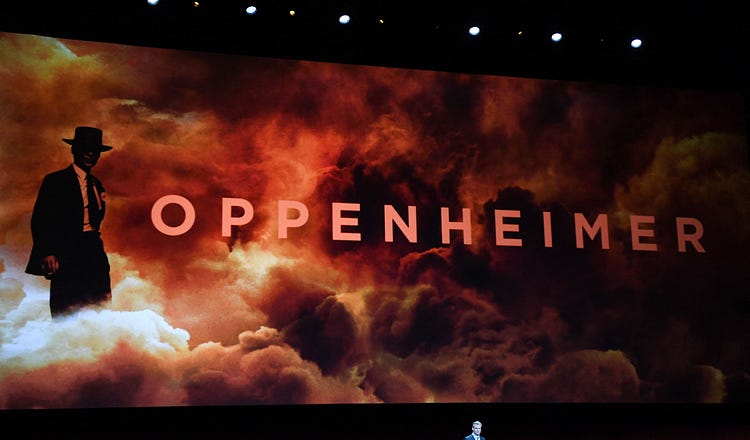

Christopher Nolan is one of the finest filmmakers working today, and Oppenheimer is perhaps his greatest achievement to date. See this movie on the biggest screen you possibly can, preferably on IMAX. The visuals are stunning; the performances, compelling—particularly that of Cillian Murphy as J. Robert Oppenheimer, whom Nolan has called “the most important man who ever lived.”

Nolan is renowned for his complex structures. In Dunkirk, the film was broken into three sections: land, a week; sea, a day; air, an hour. Those sections converge in a single moment, the film’s climax, a dramatic rescue. Oppenheimer is structured like a double helix, in two integrated parts: fusion, the bringing together of atoms, shot in black and white; and fission, their tearing apart, shot in color. Scientifically, both processes create vast amounts of potential energy.

The fission sections of Oppenheimer tell the story of the bomb’s creation by tracing the development of its creator: Julius Robert Oppenheimer. We see his intellectual development as a theoretical physicist at Cambridge and then as a professor at Berkeley—where he would meet crucial collaborators like Ernest Lawrence, who features prominently in the film—and his eventual assignment to the top-secret atomic testing facility at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where he was to become the father of the atomic bomb.

These sections are presented in vivid color, and shot beautifully by cinematographer Hoyte van Hoytema.

Braided together with the color sections of the movie are the black and white fusion sections, which center around the Senate confirmation hearings of Lewis Strauss, an Oppenheimer rival whom President Eisenhower had nominated for a Cabinet post.

The interplay between fission and fusion generates an enormous narrative energy that courses through the film. It never feels as though you’re toggling between two separate stories. Rather, it feels as though the story is vibrating, and this vibration—alternately unnerving and exhilarating—gets to the fundamental theme of the film. If Dunkirk is about people trying to get home (as Nolan has said), Oppenheimer is about the dance between creation and destruction.

But the big question is: Why this story? And why now?

The threat of a nuclear war is as significant right now as at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis, the most dangerous two weeks of the entire Cold War. Though few have noticed it, we seem to have shifted from a postwar period into a prewar one.

The old world order—the one ushered in by the bomb that Oppenheimer and his fellow scientists at the Manhattan Project birthed—was a binary one that came with a security architecture that delivered decades of peace. That architecture vanished long ago, and we are now living in a multipolar, nuclear-armed world.

America’s present-day adversaries, including Russia and China, possess nuclear arsenals that rival the Soviets’. A nascent Iranian nuclear program could produce a bomb on short notice, to say nothing of rogue nations like North Korea. Among our allies, nuclear weapons will proliferate as they become skeptical of American security guarantees and as the stability of an American-led world order gives way to a new age of great power politics. It’s no secret that nondemocratic actors outside the West seek to displace whatever is left of the old order. They’ve said as much.

Fears of nuclear war might feel as retro as the three-piece suits and fedoras worn by the Oppenheimer cast. They’re not. When nuclear powers are agitating for a reset of the international system, anything might happen.

And that’s to say nothing of artificial intelligence, a technology that many insist is the nuclear breakthrough of our age. The warning from today’s technologists echo those that Oppenheimer delivered after Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

When asked what the reaction was at Los Alamos after the first successful test of the atom bomb, Oppenheimer recalled in an interview, “We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent.” Oppenheimer then famously quoted a verse from the Bhagavad Gita in which Vishnu, to impress upon a prince the importance of doing his duty, says, “And now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

When Oppenheimer’s mentor, Nobel Prize–winning physicist Niels Bohr, played by Kenneth Branagh, is shown the progress being made on the bomb, he says, “This isn’t a weapon—it’s a new world.” In Oppenheimer, Nolan reminds us that new worlds almost always begin with a bang.

Elliot Ackerman is a former Marine. He was awarded the Silver Star, the Bronze Star with Valor, and a Purple Heart during his five deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq. His latest novel, published in May, is called Halcyon.

The Free Press earns a commission from any purchases made through Bookshop.org links in this article.

Subscribe to The Free Press

A new media company built on the ideals that were once the bedrock of American journalism.

Say what you will about his politics, but William Jennings Bryan was a sublime orator. In the closing argument (that never was) of Scopes, Bryan wrote:

“Science is a magnificent force, but it is not a teacher of morals. It can perfect machinery, but it adds no moral restraints to protect society from the misuse of the machine.”

“The threat of a nuclear war is as significant right now as at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis”

——————————————————-

It needs to be said that this is because of the Donbas Region and Hillary Clinton. Are there dumber reasons to start a nuclear war?