After wrapping the latest season of Portlandia, Carrie Brownstein escaped to the high desert of Oregon with Cricket, the younger of her two adopted dogs (Toby was too arthritic to make the trip). They stayed in a yurt, hiking around 15 miles a day, and Brownstein celebrated her 41st birthday by setting her mobile phone to airplane mode.

“So I could use it as a camera,” she explains now, a week and a half later, fishing cobb salad from a white, asymmetrical bowl that takes up half the table and makes her look tiny and childlike in comparison. When I tell her this, she laughs, saying something self-deprecating about how it’s really dark where she grew up (Seattle), so maybe she hasn’t had a lot of skin damage. I tell her she probably gets ID’d a lot, and it turns out that, yes, she does. It happened on her way to the yurt.

“I thought I should get some wine – there was this super moon,” she says. “The girl at the liquor store wanted ID and I was like, ‘This is flattering, but do you actually need me to go back to my car?’ And she was like, ‘Yes, I do.’”

We’re eating at a fancy restuarant in West Hollywood. Suddenly I hear my phone ringing in my bag and scramble to turn it off. She catches a glimpse of my phone. “Oh my God,” she says, “I love that you have a flip phone. I’m just about to go there. That’s why I started wearing a watch. You go on your phone to check the time and it becomes this five-step process: email, Twitter – I’m like, why am I checking Instagram again? Could there be a family emergency on Instagram? No. Is this a portal into world affairs?”

She warms to her theme. “I feel like it’s got to the point where I’m processing information about Syrian refugees or the latest cat video exactly the same way, because I’m mediating it through the same screen. Everything begins to share the same value. Everything’s a stage.”

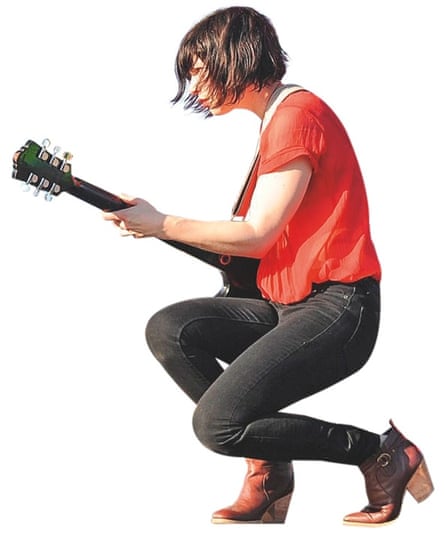

Brownstein began performing when she was still a teenager. At 19, after playing in lesser-known punk bands around Washington state, she and a friend, Corin Tucker, launched Sleater-Kinney, an all-female trio named after the street on which they used to practise. Their setup was simple (two guitars, two voices, one drummer), but their sound was new, their lyrics sharp and political. It was the tail end of the riot grrrl scene and local bands such as Bikini Kill were an early influence.

Between 1994 and 2006, Sleater Kinney released seven albums, and while their sales never broke any records, the devotion among their fans remains obsessive. But in 2006 they abruptly disbanded, disappearing for nearly nine years. They released a new album in January this year.

Meanwhile, Brownstein found a whole new audience, as the co-creator and co-star of sketch comedy show Portlandia, alongside Saturday Night Live star Fred Armisen.

The cult series, available in the UK on Netflix, skewers hipster culture in skits such as Put A Bird On It, in which Brownstein and Armisen (who play dozens of characters) are creatives in a craft shop adding bird motifs to every piece of merchandise, and Is This Chicken Local? about a couple in a restaurant obsessed with the exact provenance of the chicken they are about to order (to the point of taking a trip to the farm). Brownstein is brilliantly deadpan, whether playing a neurotic dog lover or a feminist bookshop owner. She has also been cast in more serious parts, with a recurring role in hit Amazon series Transparent and a small part in forthcoming Todd Haynes film Carol, starring Cate Blanchett.

Now, Brownstein is publishing her first book, Hunger Makes Me A Modern Girl, a memoir about her youth and the making of Sleater-Kinney. In it, she describes watching Mudhoney and Nirvana play at her school, meeting her bandmates, learning to write songs, and discovering that performance was an escape from a sometimes difficult childhood. Her mother, who suffered from anorexia, left when Brownstein was 14. Her father came out as gay when she was in her mid-20s. “There was so much I wanted to destroy,” she writes of that period. But, years later, the band would leave her feeling destroyed, reaching a nadir at a gig in Brussels in 2006, where she found herself standing backstage, punching herself in the face. “I boxed myself into oblivion,” she writes. “I was going to make myself extinct.”

It is a moment that the bandmates still haven’t discussed and, over lunch, Brownstein hastens to say that her memoir isn’t “the definitive story of Sleater-Kinney”, that it’s just her take. Of that night, she says, “It was the culmination of exhaustion and physical illness.”

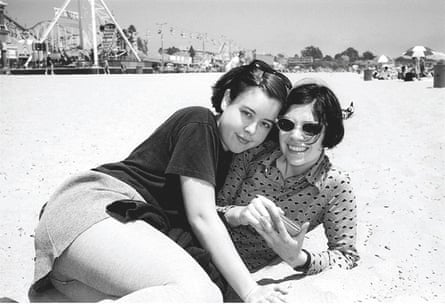

For Brownstein, Sleater-Kinney was a surrogate family. Her father was, she says, “a partial person” until he sat her down and told her he was gay: “He was laconic, more engaged with us in terms of activities than emotionally.” A few years prior to this, Spin magazine ran an article outing Brownstein’s relationship with her bandmate Tucker (they had since broken up). Brownstein says her father’s “awkwardly nonchalant” response to the piece did not, in hindsight, foreshadow his own coming out so much as his subscription to International Male: “A men’s underwear catalogue,” she writes, “that is essentially a showcase for big European cocks.”

“It was surprising, not shocking,” she says to me, “and I think it just validated a glimmer of intuition I’d had a long time. There was much more illuminating stuff, in retrospect, than my own outing. But there were no clues in that moment, because he kind of just sounded like a caring, progressive dad.”

And now? “I’ve never seen my dad happier.” She grins. “It’s sort of like discovering someone I thought I knew. He got married two summers ago to the same guy he’s always been with – a chef, and adventurer, and skier, a former dancer. A kind-hearted, gentle soul. At their wedding, my uncle said he felt like he had a new brother – but in the best way possible. The process of coming out, as much as other people want to couch it in terms of politics, it’s a very personal journey.”

Brownstein has dated men and women. Did her public outing feel like an invasion of privacy? “It did. Though when I think about it from today’s perspective, I’m actually so grateful that I was not subjected to a chorus of opinions on social media. The only person I had to deal with was myself. It felt invasive, but not public. There was no commentary on it, except in your own head. Better that it happened in 96.”

In her writing, Brownstein tends to keep her personal journeys private. She describes her mother’s illness, for instance – the visits to the hospital, her homecoming, and then abandonment – but doesn’t really revisit their relationship. When I ask whether she’s in touch with her mother, she says, “infrequently” and leaves it there. She also has a sister, Stacey, but barely mentions her. “My sister’s great,” she says, “she’s very bright, she’s very private. I think my sister loves being an observer more than I do. She appreciates the anonymity with which she’s able to examine the world and I didn’t want to take that away.”

Brownstein’s romance with Tucker gets little mention. (There is a brief reference to breaking up on a hike.) “Part of it is just respecting her privacy,” she explains, “but also, the part of our relationship that had the most meaning, to both of us, was the creative collaboration. The music: that was the love story.”

The band members’ closeness offered an oasis from the misogyny of the 1990s male-dominated punk scene. Sleater-Kinney is often described as a feminist band. “We told stories from a female perspective in a way that was unapologetic and unafraid of its own voice,” Brownstein says. “There is a forcefulness to that, that I think posits it within the context of feminism.”

When I speak to Sleater-Kinney drummer Janet Weiss, she describes how being in a band with women offered a certain sense of safety. “Early on, when you’re starting to play an instrument, it can be intimidating to be around the real techy music nerd,” Weiss says. “When you’re starting out, feeling a little insecure, these instruments are loud, embarrassing things can happen. Playing with women… I guess we felt more free. Maybe because there was this unspoken, obvious basis of mutual respect. We cherished each other.”

What about the way it ended? “Let’s just say you know you need to take a break. It’s pretty obvious.”

Tucker is more forthcoming, describing the band’s decision to take a break as being due, in part, to feeling like she and Weiss had become Brownstein’s nurses. “It was an awful, awful moment,” she says. “I was frustrated and upset, and didn’t understand, which I think is common when someone’s depressed. You come to see yourself as almost enabling the situation. It took a lot of courage to say, ‘This isn’t working, even though we love the band and love each other.’”

What happened next, I ask Brownstein. “I just kept going,” she says. “We had a tour to finish. And I think routine and ritual and structure became the scaffolding that enabled me to right myself and move forward and continue. I think it was the culmination of exhaustion, and illness.” There was always such mystery about the break-up. Why tell the real story now? “I suppose there was a slightly anaesthetised version of why we went on hiatus – the version that we presented to the public was, I think, more benign. This allows greater insight.”

After the band split, Tucker threw herself into being a full-time mother (she had married film-maker Lance Bangs in 2000 and had a son), Weiss started playing with other bands and Brownstein brought home dogs to foster. It was “just about the only way I knew how to deal with the loss”, she writes. “If you’re wondering how sad I was, you’d never know by talking to me, but you would know it by the fact that I won the Oregon Humane Society Volunteer of the Year Award in 2006, the year of Sleater-Kinney’s demise.”

Soon after that, Brownstein launched the next stage in her career: as a successful actor. Portlandia, which she created with actor-comedian Armisen, has catapulted her into the sort of fame that bugs ardent Sleater-Kinney fans, along with 14 Emmy nominations (and three wins). It all hangs on the pair’s chemistry, and their sketches satirise not just hipness but all annoying human behaviour (mobile phone salesmen with endless different phone plans, complex recycling instructions from councils).

It started as a sketch show, but in the most recent series has evolved into longer character studies. The best is The Story Of Toni And Candace, which is the origin story of the women who run the feminist bookstore (the shop is called Women And Women First). Why does Brownstein think it works? “It’s not mean-spirited, and because it’s satirical, the fact that it’s kind-hearted allows people to take a step towards it,” she says. “It feels more relatable as opposed to keeping people at a distance. I think people see themselves in it.”

What does she find funny? “That question,” she deadpans. “I really like sardonicism and wit. I love the writing of Joy Williams and Lorrie Moore. I like Tina Fey, Amy Schumer.” Is she funny? She says she considers herself “a keen observer, and occasionally witty”. When I ask what the difference is, Brownstein says, “I feel like funny people, that’s their currency, and they’re really good at using that in a room. There’s something that feels really performative about funny, and that’s usually not the currency I use interpersonally.”

When I speak to Armisen about Brownstein, he refers to Portlandia as their “hit record” and talks about their shared work ethic: “We really like to work – we’re soulmates – but that’s where we’re twins. We don’t have to deal with anything else in our lives. All we have to deal with is work.”

I ask Brownstein if she is a workaholic and she nods, but emphasises that, for her, hard work (or “momentum”, as she puts it) has become “a way of processing life”. “I experience the world in a very physical and visceral sense – I allow myself that via performance. Some people can do it with stillness and meditation. The other day I was at this dog park and these two people were doing yoga. A very public display of yoga.”

What about the dog mess?

She nods solemnly. “People like to perform.”

It sounds straight out of Portlandia. But Brownstein seems frustrated by the recent focus on the show, rather than on her music. “The nature of television means [Portlandia] becomes bigger than Sleater-Kinney,” she says. “When Sleater-Kinney went on tour this year for No Cities To Love, I bleached my hair for the first time. I wanted to differentiate myself from Portlandia. I wanted to feel a distinction from that.”

Brownstein is currently single, and when she’s not working she’s walking her dogs and seeing friends – recently she posted a picture of herself with Kim Gordon, Amy Poehler and singer Aimee Mann with the caption: “Don’t call us a squad. We’re a fucking coven.” Are they a coven? “I mean, I was joking,” Brownstein says, “but they’re a group of very inspiring women, and I suppose if they possess any magic, it’s just collective talent and kindness.’

As we chat, Jack Antonoff, songwriter, singer with the band Fun and Lena Dunham’s boyfriend, comes over to ask whether they’re going to hang out soon.

Brownstein: “I like your nail polish.”

Antonoff: “They’re stickers. From Japan. I’ve had them on, like, a month.”

Brownstein: “Do they ruin your nails?”

Antonoff: “I don’t know. They’ve been on for ever. When’s the book tour? I can’t wait to read it.”

Brownstein: “Well, Lena has it.”

Antonoff: “Well, I’ll buy a copy, like a human being, who’s not, like, awful.”

Brownstein: “I can also send you one.”

Antonoff: “No. I’m really happy to buy it.”

“Buy 10,” Brownstein says.

I ask who she is listening to at the moment and she says, “Kendrick Lamar, Miguel, Courtney Barnett, Kurt Vile and Tame Impala.” What does she think of Beyoncé and Taylor Swift, and their expression of feminism? “Well, I think both seem like generous performers and artists who use their platform to empower women and people in general. They seem very fearless.”

In her memoir, Brownstein describes the moment in 2011 that Tucker asked her, out of the blue, if she thought Sleater-Kinney would ever play again. “The answer was obvious,” she writes. They started playing together in secret, seeing if the three of them could still create the magic they had once done. They played the song Jumpers, about suicides from Golden Gate bridge, which Brownstein had written during a bout of depression (“Drink your last drink/Sin your last sin/Sing your last song”). “And this time it was not about death, it was about being alive.” When they made it back on stage, she describes tears of joy in her eyes.

I ask whether that craving for anonymity makes her concerned about publishing a candid memoir. She laughs nervously. “I guess I haven’t thought about it yet. I think you can’t be engaged with the process and the work of it with that in mind – it becomes censoring and stifling.”

As the waiter lays down our bill, she adds, “Usually I can kind of put myself in situations [like a book tour] where that energy is required of me. Those kinds of interactions are brief and not overwhelming. I’m not so well-known.” But as we cross the lobby, she immediately gets recognised. A lady approaches and, in a loud whisper, says, “Just so you know, I love your TV show.”

Brownstein smiles in a practised way. “Thanks.”

She leaves it at that, and eventually the fan’s expectant smile vanishes; she takes her cue to leave. Brownstein is so much more self-contained than the younger self she describes in her memoir. After overextending herself for so long, stretching her limits to the brink, she has found stillness. She has boundaries. She can turn off her phone, hiking for days in the mountains.

Hunger Makes Me A Modern Girl by Carrie Brownstein is published next month by Virago. Order a copy for £11.89 from the guardian bookshop.