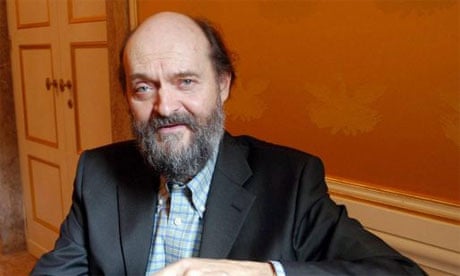

Happy Christmas! If you're Russian Orthodox, today is Christmas Eve; and I'm in the middle of Slavic celebrations because I'm in a hotel in Tallinn, a city that's full of Russian tourists making the most of their Christmas and new year in the beautiful Estonian capital. I've been here to interview Arvo Pärt, the famous Estonian composer, and someone who has a reputation as a shy recluse; a seeming paradox given that his music is celebrated all over the world.

He talked to me in the building that houses his archive – a half-hour drive through the snow, forest and flatness of the landscape outside Tallinn, a journey that felt like a pilgrimage to a mythical musical hideaway – and I found Pärt to be the exact opposite of the forbidding, taciturn figure that looms out of some of his photos. There was laughter, humour and generosity in the way he spoke about his compositional and existential struggles, and even his religious feelings. You can hear the interview on Radio 3's Music Matters on Saturday 15 January, but as a preview, here are a couple of things Pärt revealed about his music, especially from around the time of his consolidation of the technique of "tintinnabulation", which has defined his music from the mid-1970s to this day.

In one of the rooms in the house, there was a row of plant pots. It turns out they were more than mere decoration: they were painted by Pärt in 1977, because working with riotously festive colours was one of the ways he got through the hard years of writer's block. "You have to do something to keep your creativity going," he told me. But the real epiphany that set Pärt on his course of what sounded like a radical simplicity in the mid-70s, producing works such as Tabula Rasa, Fratres, and Passio, which poured out of him later that decade, was an encounter with a street cleaner outside his house in Tallinn. Searching for a solution that would connect his emotional, musical and spiritual lives together, Pärt, at a loss for inspiration, went outside into the snow one morning and asked the cleaner: "What should a composer do?" "Well, he should love every note," was the reply. "No professor had ever told me something like that," Pärt said, and this single sentence crystallised his thinking. He realised that to really love every note, to really understand the connections between even a tiny handful of musical pitches, could be the source of lifetime of composition and contemplation.

Pärt's music is some of the most immediate and recognisable of any contemporary composer, and its familiarity has made some hear in it only a facile style of "holy minimalism," where for others, it has life-changing power. To meet him was to discover the deep philosophical, biographical, musicological and even biological roots of his music. As well as to hear the mathematical-musical riddle that he told me was one of the secrets to understanding his work: "One and one makes – one." I'll leave you to ponder that, before the solution is revealed on the radio next Saturday.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion