2. Ariosophy

Übermensch

As reported by Charles Novak, the Asiatic Brethren moved to Denmark, where they were comprised largely of members of the Baltic aristocracy, where they adopted the swastika of Buddhism as a symbol for recognizing each other.[1] The order would also take on völkisch and pan-German tendencies which would go on to inspire the messianic expectations around the rise of Adolf Hitler. The evolution of history, following the Kabbalah of Isaac Luria, would culminate in the advent of the first man who dares to recognize that he is God—in other words, Friedrich Nietzsche’s Übermensch (“Superman”), or what some would interpret at the anti-Christ, a role the Nazis believed was fulfilled by Hitler. The Nazis declared that they were dedicated to continuing the process of creating a unified German nation state begun by Otto von Bismarck, a member of the super-rite of Freemasonry founded by Albert Pike and Giuseppe Mazzini, known as the Palladian Rite. The Third Reich, meaning Third Empire, alluded to the Nazis’ perception that Nazi Germany was the successor of the earlier Holy Roman Empire (800–1806), beginning with the crowning of Charlemagne in 800 and which was dissolved during the Napoleonic Wars in 1806, and the German Empire (1871–1918), which lasted from the unification of Germany in 1871 by Otto von Bismarck under Kaiser Wilhelm I until the abdication of his grandson Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1918 at the end of World War II. Although Bismarck had excluded Austria and the German Austrians from his creation of the Kleindeutschland state in 1871, integrating the German Austrians nevertheless remained a strong desire for many people of both Austria and Germany behind the Pan-German movement which influenced the racist fascism of Nazis.

Nietzsche, who was foundational to the delusions of the Nazis, was frequently published in Pan-German newspapers. In The Antichrist (1888), Nietzsche declared, “Let us look each other in the face. We are Hyperboreans—we know well enough how remote our place is,” and after quoting Pindar, he commented, “Beyond the North, beyond the ice, beyond death—our life, our happiness.” In On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche introduces one of his most controversial images, the “blond beast”—the Aryan race—which he compares to a “beast of prey,” impelled by a “good,” which is an irresistible instinct for mastery over others. It was through his formulation of an idea related to the blond beast, the Übermensch (“Superman”), that Nietzsche inspired the fascist ideal of the New Man, with an excessive emphasis on male virility. As well, Nietzsche’s mental illness would come to be perceived as a model for the sentimental notion of “divine madness,” an idea linked by Plato to mystic prophecy and the adoration of male beauty.[2] Ultimately, based on the homoerotic fascination with the male as the sole object of affection, fascism is a perverse form of machismo, where notions of compassion are denigrated as “feminine,” and the purported virtues of dispassionate discipline and self-serving violence are celebrated as “masculine.”

Aleister Crowley, leader of the German branch of the satanic OTO, was also inspired by Nietzsche. Crowley made Nietzsche a saint in the Gnostic Catholic Church and wrote in Magick Without Tears that “Nietzsche may be regarded as one of our prophets...” Crowley also wrote his own “Vindication of Nietzsche.” The Book of the Law declared that its followers should adhere to the code of “Do what thou wilt” and seek to align themselves with their “True Will” through the practice of magick. Magick, in the context of Crowley’s Thelema, is a term used to differentiate the occult from stage magic and is defined as “the Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will.” Explaining his interpretation of magick, Crowley wrote that “it is theoretically possible to cause in any object any change of which that object is capable by nature.”[3] Crowley applies a Nietzschean interpretation to his dictum of “Do What Thou Wilt,” where in the Aeon of Horus the strong, who have realized their true will, will rule over the slaves whose weakness has brought about their self-enslavement. In it, we find the seeds of a fascist occult ideology:

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law… Come forth, o children under the stars and take your fill of love… These are the dead, these fellows; they feel not… the lords of the earth are our kinfolk… We have nothing with the outcast and unfit: let them die in their misery… Compassion is the vice of kings: stamp down the wretched & the weak: this is the law of the wrong… lust, enjoy all things of sense and rapture… Pity not the fallen… strike hard and low, and to hell with them… be strong, then canst thou bear more joy. I am a god of War and of Vengeance… smite the peoples and none shall stand before you… Conquer! That is enough… Worship me with fire & blood; worship me with swords & with spears… let blood flow to my name. Trample down the heathen… I will give you of their flesh to eat!… damn them who pity. Kill and torture… I am the warrior Lord… I will bring you to victory and joy… ye shall delight to slay.[4]

“War is essential” declared Nietzsche.[5] In Beyond Good and Evil, he explained, “Here one must think profoundly to the very basis and resist all sentimental weakness: life itself is essentially appropriation, injury, conquest of the strange and weak, suppression, severity, obtrusion of peculiar forms, incorporation, and at the least, putting it mildest, exploitation—but why should one for ever use precisely these words on which for ages a disparaging purpose has been stamped?”[6] Nietzsche called for “a conqueror- and master-race which, organized for war and with the force to organize unhesitatingly lays its terrible claws upon a populace perhaps tremendously superior in numbers but still formless and wandering.”[7] In order to dispend one’s ressentiment, one must become like a pillaging Viking or Homeric hero, an artist of expressive violence.[8] Such is the übermensch:

Some time, in a stronger age than this mouldy, self-doubting present, he will come to us, the redeeming man of great love and contempt… This man of the future will redeem us not just from the ideal held up till now, but also from the things which have to arise from it, from the great nausea, the will to nothingness, from nihilism, that stroke of midday and of the great decision which makes the will free again, which gives earth its purpose and man his hope again, this antichrist and anti-nihilist, this conqueror of God and nothingness—he must come one day…[9]

Zeev Sternhell lists virility as one of many qualities and cults that characterize the “new civilization” desired by fascism, yet those cults, explains Barbara Spackman, in Fascist Virilities: Rhetoric, Ideology, and Social Fantasy in Italy, correspond to a single master term, virility, implying youth, duty, sacrifice, strength, obedience, sexuality and war.[10] During the same era, the belief was grounded in science that females were biologically inferior to men. It is for this reason that the active pursuit of exercise and modern sports was strongly recommended as a measure to increase masculinity and combat any signs of femininity.[11] According to Nietzsche:

Another thing is war. I am naturally warlike. Attacking is one of my instincts. Being able to be an enemy, being an enemy — these require a strong nature, perhaps; in any case every strong nature presupposes them. It needs resistances, so it seeks resistance: aggressive pathos is just as integrally necessary to strength as the feeling of revenge and reaction is to weakness. Woman, for instance, is vengeful: that is a condition of her weakness, as is her sensitivity to other people’s afflictions.[12]

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900)

Nietzsche’s revolutionary New Man of the future, the Übermensch or “Superman,” must strip away all values of conventional weak morality, including equality, justice and humility. We must have an Umwertung aller Werte, the “revaluation of all values.” The man of the future must be a beast of prey, an “artist of violence’’ creating new myths, new states based upon the essence of human nature, which Nietzsche identifies as Wille zur Macht, the “Will to Power” being a “a will to war and domination.” What Nietzsche prescribes then is a return to the pre-Christian past, before Jewish monotheism, even before Socrates and Plato who demonstrated that there must be a self-subsisting Good which is connected to the evolution of the universe. Modern man must “eternally return” to the earliest strata of human intellectual life, when man was just starting to construct his own god-myths.

While his critics argued that Nietzsche’s disturbed ideas were a reflection of his mental illness, as explains Steven E. Aschheim in The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany, 1890-1990, the pro-Nietzscheans, “sought instead to endow Nietzsche’s madness with a positively spiritual quality. The prophet had been driven crazy by the clarity of his vision and the incomprehension of a society not yet able to understand it...”[13] “How do we know,” wrote Isadora Duncan in 1917, “that what seems to us insanity was not a vision of transcendental truth?”[14] Nietzsche finally suffered total mental collapse in 1889. As the story goes, he was taken away by two policemen following an altercation after he witnessed the flogging of a horse at the other end of the Piazza Carlo Alberto in Turin. In a last but desperate and misplaced expression of compassion, contradicting all his former pessimism, Nietzsche ran to the horse, threw his arms up around its neck to protect it, and then collapsed to the ground.[15] Within a week, Nietzsche’s family brought him back to Basel, where he was hospitalized and diagnosed with the syphilis. The Nietzsche scholar Joachim Köhler has attempted to explain Nietzsche’s life history and philosophy by claiming that Nietzsche was a homosexual, and he argues that his affliction with syphilis, which is “usually considered to be the product of his encounter with a prostitute in a brothel in Cologne or Leipzig, is equally likely, it is now held, to have been contracted in a male brothel in Genoa.”[16]

Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth Alexandra Förster-Nietzsche (1846 – 1935)

As his caretaker, Nietzsche’s sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche (1846 – 1935) assumed the roles of curator and editor of her brother’s works. She was married Bernhard Förster (1843 – 1889) who became a leading figure in the anti-Semitic faction on the far right of German politics and wrote on the Jewish question, characterizing Jews as constituting a “parasite on the German body.”[17] In order to support his beliefs, Bernhard set up the Deutscher Volksverein (German People’s League) in 1881 with Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg (1848 – 1911), a German officer who became noted as an anti-Semitic politician and publisher. Von Sonnenberg was part of a wider campaign against German Jews that became a central feature of nationalist politics in Imperial Germany in the late nineteenth century. Following a conference of anti-Semites in Bochum in 1889, von Sonnenberg set up his own political party, the Deutsch-Soziale Partei, which became the Deutschsoziale Reformpartei when it merged with Otto Böckel’s Deutsche Reformpartei in 1894. The party, who main basis was anti-Semitism, was active in 1898 in support of campaigns to restrict the immigration of Russian Jews into Germany and argued that such laws could form the basis of their ultimate aim of removing rights from all Jews in Germany.[18] Wilhelm Giese emerged as a prominent member of the group and was especially noted for his criticism of Zionism, an idea that had some support among contemporary anti-Semites as a possible solution to the "Jewish problem.” In 1899, Giese ensured that the party adopted the Hamburg Resolutions explicitly rejecting removing the Jews to a new homeland and instead called for an international initiative to handle the Jews by means of complete separation and final destruction of the Jewish nation.”[19] The program helped to lay the foundations for the future Final Solution, a term it used.[20]

Bernhard Förster planned to create a “pure Aryan settlement” in the New World, and had found a site in Paraguay which he thought would be suitable. The couple persuaded fourteen German families to join them in the colony, to be called Nueva Germania, and the group left Germany for South America in 1887. The colony failed miserably. Faced with mounting debts, Förster committed suicide by poisoning himself in 1889. Four years later, Elisabeth left the colony and returned to Germany. Friedrich Nietzsche’s mental collapse occurred by that time, and upon Elisabeth’s return in 1893 she found him an invalid whose published writings were beginning to be read and discussed throughout Europe. Elisabeth took a leading role in promoting her brother, especially through the publication of a collection of his fragments under the name of The Will to Power. She reworked his unpublished writings to fit her own ideology, often in ways purportedly contrary to her brother’s stated opinions. Through Elisabeth’s editions, Nietzsche’s name became associated with German militarism and National Socialism, while later twentieth-century scholars have strongly disputed this conception of his ideas.

Café Central, Vienna

Vienna (1913)

The Nordic mythology celebrated by Nietzsche’s friend, the composer Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883), deeply inspired the Pan-German movement, which ultimately inspired the Nazis. Although Otto von Bismarck had excluded Austria and the German Austrians from his creation of the Kleindeutschland state in 1871, integrating the German Austrians nevertheless remained a strong desire for many people of both Austria and Germany behind the Pan-German movement. Driven by the völkisch movement, it was influenced by the notion of a German “volk” expressed by Romantic nationalists like the brothers Grimm, Herder and Fichte. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify the Germans of the Second Reich with the other Germanic-speaking peoples into a single nation-state known as Großdeutschland. A new element was included in 1879 with the introduction of the neologism “anti-Semitism,” marking a break from “anti-Judaism,” favoring a racial and scientific notion of Jews as a nationality instead of a religion.[21]

Völkisch Pan-Germanism began as the ideology of the small minority of Germans in Austria who refused to accept their permanent separation from the rest of Germany after 1866, which they determined to repair through the Anschluss of what they called German-Austria. Vienna, capital of the multinational Hapsburg Empire, rivaled Paris as Europe’s cultural center during the reign of Franz Josef (1848 – 1916), Grand Master of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Less than half of Vienna’s two million residents were Austrian, while about a quarter came from Bohemia and Moravia—the strongholds of the Sabbateans sect—so that Czech was often spoken alongside German.[22] It was reported in the 1840s that Jews professing Christianity were found filling the offices of the ministry, and that Frankists had been discovered and probably existed among the Catholic and Protestant church dignitaries of Russia, Austria and Poland.[23] Sigmund Freud’s family came from Moravia in the 1860s.

However, although an extensive religious literature was still in the possession of Frankists in Moravia and Bohemia at the beginning of the nineteenth century, their descendants tried to obliterate any shred of evidence of their ancestors’ beliefs and practices. Nevertheless, most of the families once associated with the Sabbateanism in Western and Central Europe continued to remain afterward within the fold of Judaism, and many of their descendants, particularly in Austria, rose to positions of importance during the nineteenth century as prominent intellectuals, great financiers, and men of high political connections.[24]

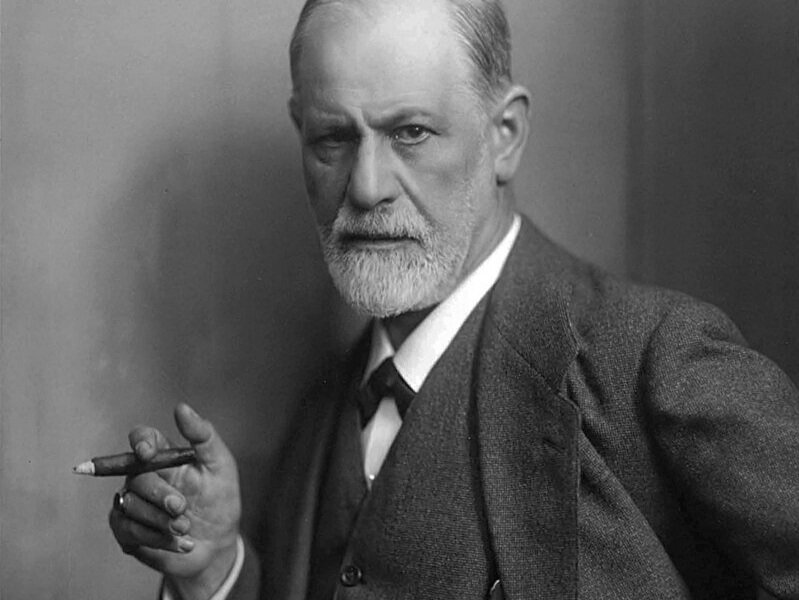

Sigmund Freud (1856 – 1939)

Barriers to Jewish emancipation were gradually lifted by the Habsburg authorities as part of an overall policy of modernization. In 1852, a royal statute granted Jewish the right to establish a religious community in the city, and the authority to tax and regulate itself. In 1962, Jews were granted access as residents of all municipalities. In 1864, all restrictions on Jewish landownership were lifted. And in 1867, the law granted Parliament the power to establish equal rights regardless of religious affiliation, allowing Jews to become full citizens. These liberties permitted the rise of a new Jewish middle class, that was no longer represented by merely a small elite of private bankers. Nevertheless, despite often falling away from the practice of Judaism itself, assimilated Jews tended to cluster in certain districts of Vienna, and around specific occupations. Rates of conversion and intermarriage remained low. Martin Freud, Sigmund Freud’s son, described his time in Vienna with his family as having abandoned Judaism while remaining Jewish by identify though moving in exclusively Jewish social circles.[25]

Freud frequented the Cafe Landtmann, while Trotsky and Hitler often visited Cafe Central. The cultural eclecticism of the city created a unique cultural phenomenon, the Viennese coffee-house, a legacy of the Ottoman army following the failed siege of 1683. The coffee-houses provided an important source of activity for the city’s Jewish intelligentsia, and new industrialist class, made possible following their being granted full citizenship rights by Franz Joseph in 1867, and full access to schools and universities. [26] Coffee was first used by the Sufis of Yemen, to help them stay awake during their night rituals, and the drink caught on immediately, explains Gil Marks in his Encylopedia of Jewish Food. Coffee, often with sugar added to counteract its bitter taste, quickly spread throughout the Ottoman Empire. Religious Jews, like the Muslims, also drank it to stay alert for nightly devotions, says Israeli professor of history Elliott Horowitz in his article “Coffee, Coffeehouses, and the Nocturnal Rituals of Early Modern Jewry.” Horowitz dates the use of coffee for these purposes back to the followers of Isaac Luria, following a practice popularized by him and his disciples, as the recitation of a midnight rite known as Tikkun Hazot, for mourning the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem.[27]

Cafe Griensteidl, Vienna (1897)

The first coffee-houses opened in Constantinople around 1550, then in Damascus, Mecca and Cairo. It was a Jew who exported the establishment to Europe, opening the first in Livorno, Italy in 1632. In 1650, a Lebanese known as “Jacob the Jew” founded the first English coffeehouse in Oxford. Sephardic Jews, many of whom also became coffee traders, soon joined with Armenian and Greek merchants to bring the coffeehouse to the Netherlands and France. By the nineteenth century, coffeehouses in Berlin, Vienna, Budapest and Prague were at the forefront of societal change. Figures such as writer Stefan Zweig, psychologist Alfred Adler and the young journalist and playwright Theodor Herzl were among those who joined the coffeehouses in Vienna. Zweig once described the scene as “a sort of democratic club, open to everyone for the price of a cheap cup of coffee, where every guest can sit for hours with this little offering, to talk, to write, play cards, receive post, and above all consume an unlimited number of newspapers and journals.” [28]

Julius Meinl, a company is based in Vienna, Austria, is a manufacturer and retailer of coffee, gourmet foods and other grocery products. The Julius Meinl name is synonymous with the family business, and the brand is one of the most well-known and prestigious in Austria. Julius Meinl I was a notable coffee retailer from Bohemia who opened a coffee roasters in Vienna. Julius Mienl III fled Austria during WWII due to the fact that his wife was Jewish.[29] Julius Meinl V worked for the Swiss Bank Corporation and Brown Brothers Harriman.[30]

Wagner

Scene designs for the controversial 1903 production at the Metropolitan Opera: Gurnemanz conducts Parsifal to Monsalvat (Munsalvasche).

Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883), and his wife Cosima, illegitimate daughter of composer Franz Liszt and Countess Marie d’Agoult

Pan-Germanism was widespread among the revolutionaries of 1848, notably among Richard Wagner— Nietzsche’s friend and idol—and the Brothers Grimm, and was highly influential in German politics in the nineteenth century during the unification of Germany when the German Empire was proclaimed as a nation-state in 1871, with the exclusion of Austria. Although reportedly not a Freemason, Wagner had expressed interest in joining the fraternity, and had many Masonic influences in his life, including his family and friends. His brother-in-law, Prof. Oswald Marbach (1810 – 1890, was one of the most important personalities in Freemasonry during Wagner’s time. In view of the Masonic aspects of Wagner’s opera Parzival, it is speculated that he learned much of Masonic ritual and ideas from Marbach.[31] Another great friend was the banker, Friedrich Feustel (1824 – 1891), who from 1863-69 was Grand Master of the lodge Zur Sonne in Bayreuth. In 1847, Feustel proposed that the lodge abolish the restrictions on non-Christians becoming members. Wagner informed Feustel of his wish to join the lodge Eleusis zur Verschuregenheit in Bayreuth, but was advised against it as there were members who were critical of Wagner’s personal life. Feustel suggested to Wagner that his admission to the lodge would strengthen the opposition of the Bavarian clericals if it was known he was a member of the Craft.[32]

As a young man Wagner had been influenced by the occult novels of Sir Edward Bulwer-Lytton, and his first successful opera Rienzi, completed in 1840, was based on one of Bulwer-Lytton’s novels. Wagner’s play was based on the real-life exploits of Cola di Rienzo (1313 – 1354) whose demagogic rhetoric, anti-establishment and populist appeal some considered an early form of proto-fascism.[33] The resulting aristocratic anarchy in Rome that resulted from the struggle between the Orsini and the Colonna provided the setting Cola di Rienzo to seize power in Rome in 1347, declared himself Tribune, his aim being to recreate the power and glory of Ancient Rome by conquering Italy and ultimately the whole world. However, Rienzo met a violent death in 1354 when was assassinated by supporters of the Colonna family. To many, he was merely a megalomaniac who used the rhetoric of Roman renewal and rebirth to mask his quest for power.[34] Petrarch, who encouraged and then deserted him, wrote one of his finest odes, Spirito gentil, where Rienzo was the hero.

A copy of a French biography of Rienzo by De Cerceau (1733), was found in Napoleon’s possessions after Waterloo. Having advocated both the abolition of the Pope's temporal power and the unification of Italy, Rienzo re-emerged as a romantic figure in the nineteenth century, as a precursor of the Risorgimento led by Giuseppe Mazzini. Cola di Rienzo’s life and fate have formed the subject of a novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1835), tragic plays by Gustave Drouineau (1826), Mary Russell Mitford (1828), Julius Mosen (1837), and Friedrich Engels (1841), and also of some verses of Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1818) by Lord Byron. In 1873, only three years after the founding of new Kingdom of Italy, the rione Prati was laid out, with the new quarter’s main street being Via Cola di Rienzo and a conspicuous square, Piazza Cola di Rienzo.

Illustration of Wagner’s opera Rienzi, based on a novel of the same name by Edward Bulwer-Lytton.

With his second wife Cosima, Wagner founded the Bayreuth Festival as a showcase for his stage works. Cosima was 24 years younger than him and was herself illegitimate, the daughter of the Countess Marie d’Agoult, who had left her husband for Franz Liszt. Marie was the daughter of Alexandre Victor François de Flavigny (1770 – 1819), French nobleman, and Maria Elisabeth Bethmann, from an old family of German Jewish bankers converted to the Protestant Christianity. Marie recalled in her memoirs, writing under the pseudonym Daniel Stern, about having met the German poet Goethe, a member of the Illuminati, and that when he caressed her hair that she felt blessed by his “magnetic hand.”[35] From 1835 to 1839, she lived with Franz Liszt, and became close to Liszt's circle of friends, including Frédéric Chopin, who dedicated his 12 Études, Op. 25 to her. Liszt’s “Die Lorelei,” one of his very first pieces, based on text by Heinrich Heine, was also dedicated to her.

Marie visited the Paris salon of Juliette Adam, who was a member of Papus’ Groupe Independant d’Études Ésoteriques, and a close friend of Blavatsky’s associate, Juliana Glinka, who was responsible for leaking the Protocols of Zion to Sergei Nilus.[36] Marie became the leader of her own salon, where the ideas that culminated in the Revolution of 1848 were discussed by the outstanding writers, thinkers, and musicians of the day. She maintained a correspondence with Giuseppe Mazzini, whose letters were sometimes read aloud in her salon. During the Second Empire, Marie held a salon in which Republicans such as Émile Ollivier, Jules Grévy, Carnot, Émile Littré and the economist Dupont-White met. Karl Marx visited her salon in 1844. Wagner was active among socialist German nationalists in Dresden, regularly receiving such guests as the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. Bakunin had also played a leading role in the May Uprising in Dresden in 1849, helping to organize the defense of the barricades against Prussian troops with Wagner. Wagner was also influenced by the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.[37]

Commentators have recognized Cosima as the principal inspiration for his later works, particularly Parsifal. Wagner’s Lohengrin was based on Wolfram von Eschenbach’s story of the Knight Swan in Parzival, which was composed at Wartburg Castle, site of the Miracle of the Roses of Elizabeth of Hungary, and where where Martin Luther translated the New Testament of the Bible into German. Tannhäuser was based on the Wartburgkrieg, when Wolfram produced Parzival as part of a minstrel contest against Heinrich von Ofterdingen and magician Klingsor of Hungary, who foretold the birth of Elizabeth of Hungary. Interest in the minstrels grew in popularity, as evidenced by the publication of “Heinrich von Ofterdingen” by Novalis in 1802. An account of the Wartburgkrieg was also found in the Grimm Brothers’ Deutsche Sagen. In the early twentieth century, nationalistic German writers portrayed Heinrich as a defender of veritable German poetry and even as author of the Nibelungenlied poem.

Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen are based loosely on characters from the Norse sagas and the Nibelungenlied, translated as The Song of the Nibelungs, is an epic poem written around 1200 in Middle High German. The poem is quoted by Wolfram von Eschenbach in his Parzival and Willehalm and likely inspired his unfinished Titurel.[38] Wagner’s Parsifal is loosely based on Wolfram’s Parzival about the Arthurian knight Parzival (Percival) and his quest for the Holy Grail. However, in Wagner’s version, the grail is a cup not a stone Wagner wrote, “The Grail, according to my own interpretation, is the goblet used at the Last Supper in which Joseph of Arimathea caught the Saviour’s blood on the Cross.”[39]

Wagner adopted the idea of “Aryan Christianity” from Arthur Schopenhauer and wrote the quest for the grail as its symbolic theme in 1849. Wagner had alluded in his essay “Wibelungen” of the idea of the Christian Grail as an allegory of the racial Aryan character of Christianity. He implied that its birthplace was not in Jewish Jerusalem but its true Aryan origin was in India. It has been suggested that Parsifal was written in support of the racist ideas of Arthur de Gobineau, an advocate of Aryanism, as Wagner had read Gobineau’s An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races.[40] Parsifal is proposed as the “pure-blooded” (i.e. Aryan) hero who overcomes Klingsor, who is perceived as a Jewish stereotype, particularly since he opposes the purportedly Christian Knights of the Grail.[41]

Nietzsche was a member of Wagner’s inner circle during the early 1870s, and his first published work, The Birth of Tragedy, proposed Wagner’s music as the Dionysian “rebirth” of European culture in opposition to Apollonian rationalist “decadence.” However, Nietzsche broke with Wagner following the first Bayreuth Festival, expressing his displeasure in “The Case of Wagner” and “Nietzsche contra Wagner.” Nietzsche thought Wagner had become too involved in the Völkisch movement and antisemitism. Although Wagner expressed anti-Semitic views in Jewishness in Music, he had Jewish friends, colleagues and supporters throughout his life. Wagner himself feared he might be Jewish himself, through his probable actual father, the actor and Freemason Ludwig Geyer, a fact hinted at by Nietzsche in 1888, in the afterword to “The Case of Wagner.”[42]

Neuschwanstein Castle, Bavaria, Germany

King Ludwig II of Bavaria (1845 – 1886)

OTO founder Theodor Reuss was a professional singer in his youth and took part in the first performance of Wagner’s Parsifal at Bayreuth in 1882. In 1873, Reuss first met Wagner, along with Wagner’s patron, King Ludwig II of Bavaria (1845 – 1886). Like his father, Maximilian II (1811 – 1864), and his grandfather, Ludwig I (1786 – 1868), Ludwig II was also a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Ludwig I had an affair with Lady Jane Digby, a friend and traveling companion of H.P. Blavatsky.[43] Digby was close friends with Wilfred Scawen Blunt, who was Jamal ud Din al Afghani’s British handler along with Edward G. Browne.[44] Blunt married Lady Anne was also friends with Jane Digby and Sir Richard Burton, a member of the so-called Orphic Brotherhood led by Edward Bulwer-Lytton. Lady Jane died in Damascus, Syria as the wife of Arab Sheikh Medjuel al Mezrab.

Ludwig II was probably the savior of the career of Wagner, who had a notorious reputation as a philanderer, and was constantly on the run from creditors. Without Ludwig, Wagner’s later operas are unlikely to have been composed, much less premiered at the prestigious Munich Royal Court Theatre. A year after meeting the Ludwig, Wagner presented his latest work, Tristan und Isolde, in Munich to great acclaim. Ludwig provided the Tribschen residence for Wagner in Switzerland, where Wagner completed Die Meistersinger. The restoration of Wartburg castle. completed in 1860, inspired Ludwig II’s construction of the famous Castle Neuschwanstein in southern Bavaria, an homage to the legend of the Knight Swan, and whose walls are decorated with scenes used in Wagner’s operas, including Die Meistersinger, as well as Tannhäuser, Tristan und Isolde, Lohengrin, Parsifal.

Burschenschaft Albia

Theodor Herzl (1860 – 1904) the founder of modern Zionism, with members of the German nationalist student fraternity Albia, to which he belonged from 1880 to 1883.

Georg von Schönerer (1842 – 1921)

Despite its open anti-Semitism, the Pan-German movement, which flourished mainly in Vienna, was closely associated with Jews who sought resolve the age-old “Jewish Question” through full assimilation into German nationality, a tendency that initially inspired the Zionism of Theodor Herzl (1860 – 1904). Zionism was also born in Vienna, a city where Pan-Germanism simultaneously flourished. Theodor Herzl, an Austro-Hungarian Jew, is considered the founder of the Zionist movement. Herzl was born in the in Pest, now eastern part of Budapest, in the Kingdom of Hungary, to a secular Jewish family. In 1878, the family moved to Vienna, and Herzl studied law at the University of Vienna. In Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism, Jacques Kornberg has argued that Herzl was a German nationalist during his student years. As a young law student, Herzl became a member of the German nationalist Burschenschaft (fraternity) Albia, in full knowledge of its opposition to the “Jewish spirit,” according to Kornberg.[45] After reading Moses Hess’ Rome and Jerusalem, Herzl proclaimed the Latin Fiducit, a term he learned from Albia, where it was a response to a toast during sessions at German Studentenkneipen, or student pubs.

According to Kellner, “At that time the waves of the German nationalist movement were rising high in this student association; Herzl was one of its most enthusiastic champions.”[46] The leading exponent of German nationalism at the time was Georg von Schönerer (1842 – 1921), who advocated for the annexation of Austria by Germany. Schönerer’s father, Mathias, a railroad contractor in the employ of the Rothschilds, left him a large fortune. His wife was a great-granddaughter of Rabbi Samuel Löb Kohen, who died at Pohrlitz, South Moravia, in 1832.[47] Like many other Austrian pan-Germans, Schönerer hoped for the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and an Anschluss with Germany. Schönerer’s movement only allowed its members to be Germans and none of the members could have relatives or friends that were Jews or Slavs, and before any member could get married they had to prove “Aryan” descent and have their health checked for any potential defects.[48]

Schönerer was a major exponent of pan-Germanism and German nationalism in Austria and a fierce antisemite, whose agitation exerted much influence on the young Adolf Hitler. According to Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, “[völkisch pan-Germanist Georg von Schönerer’s] ideas, his temperament, and his talent as an agitator, shaped the character and destiny of Austrian Pan-Germanism, thereby creating a revolutionary movement that embraced populist anti-capitalism, anti-liberalism, anti-Semitism and prussophile German nationalism.”[49] Schönerer’s views and philosophy would go on to exercise a great influence on Hitler and the Nazi Party as a whole. Hannah Arendt called von Schönerer the “spiritual father” of Hitler.[50] Schönerer, who had adopted the swastika as a völkish symbol,[51] was addressed by his supporters as the Führer and himself and his followers also used the “Heil” greeting, two things Hitler and the Nazis later adopted.[52]

William McGrath has identified a long list of Jewish students in the 1870s and early 1880s associated with radical nationalist student societies. As members of the circle of Engelbert Pernerstorfer, they were among the charter members of the Leserverein der deutschen Studenten Wiens, which was focused almost exclusively on extreme German nationalism, and influenced by the idea of Shopenhauer, Wagner and Nietzsche. Among them were Viktor Adler, the future leader of the Austrian Social-Democrats; Heinrich Friedjung, who became Austria’s foremost German nationalist historian; Gustav Mahler, the composer, Sigmund Freud; Arthur Schnitzler; Heinrich Braun, a close friend of Freud’s a later a prominent Social-Democrat in Germany. Of Theodor Meynert, one of the professors of the leseverein, to which he frequently delivered lectures on psychiatry, Freud said, “the great Meynert, in whose footsteps I followed with such veneration.”[53] Having graduated in 1881, Adler worked as assistant of Meynert at the psychiatric department of the General Hospital. Adler married Braun’s wife Emma. Their son was Friedrich became a close friend of Albert Einstein.[54] One Austrian historian recalled student meeting where Adler and Friedjung joined others in singing “Deutschland über alles” while Mahler accompanied them on the piano with “O du Deutschland, ich muss marchieren” (“O you Germany, I must march”).[55]

In his memoirs, Arthur Schnitzler recalled a popular saying on those days: “Anti-Semitism did not succeed until the Jews began to sponsor it.”[56] Members of the Pernerstorfer circle, especially Adler, Pernerstorfer and Friedjung were the moving spirits, together with von Schönerer, in founding the Deutsche Klub, and were the major contributors to the charter of the deutschnational movement. “The charter, which influenced all the mass political movements of modern Austria, centered on demands for radical social and political reform as well as for the satisfaction of extreme German nationalist ambitions.”[57] By 1878, the Leseverein was dissolved as a danger to the state, but by 1881 its leadership managed to completely takeover the Akademische Lesehalle.[58]

Despite his close friendship with Jews, Pernersdorfer wrote in 1882 that, “the Jews with their ancient, dominating racial characteristics still confront the Indo-Germanic peoples… as alien and unchanging.”[59] Along with Schönerer, Adler, Friedjung and Pernerstorfer were supporters of the Linz Program of 1882, a political platform that called for the complete Germanization of the Austrian state. Ultimately, Adler and the others wanted Austria to exist separate from the Habsburg Monarchy, which controlled much of central Europe at the time; instead, they wanted to tie themselves as close as possible to Germany. However, Schönerer's increasingly antisemitic policies culminated in the amendment of an Aryan paragraph, a clause that reserved membership solely for members of the “Aryan race” and excluded from such rights any non-Aryans, particularly those of Jewish and Slavic descent. Being one of the first documented examples of such a paragraph, countless German national sports-clubs, song societies, school clubs, harvest circles and fraternities followed suit to also include Aryan paragraphs in their statutes. The rise of ant-Semitism drove away Adler and Pernerstorfer, who became leaders of the Socialist party, while Friedjung returned to the liberal fold. Nevertheless, their experiences in the deutschnational continued to influence their outlooks.[60]

It was at this time that Herzl joined the Leseverein. MacGrath also established that Herzl’s close friend Oswald Boxer was a member in 1880-1881 of the Deutscher Klub. In the fall of 1880, Albia became affiliated with the Akademische Lesehalle. During the semester when Herzl joined, von Schönerer delivered a speech that was enthusiastically received.[61] Leon Kellner, a Viennese contemporary and author of an early biography, reported that in December 1880, Herzl was chairman of the Lesehalle’s social club, which organized beer-drinking evenings featuring German nationalist songs. Schnitzler, a fellow student and friend of Herzl during his university years, described him as a “German-national student and spokesman in the Akademische Lesehalle.”[62]

Many of Albia’s members looked forward to the full assimilation of Jews into the German nation. Both Karl Becke and Dietrick Herzog spoke positively about the Jewish brethren who “felt German” and were genuinely devoted to Albia.[63] Herzl knowingly entered Albia with the intent of shedding his Jewishness and embracing German nationality. Herzl believed that Jews were plagued by vices and corruption and that Judaism was backwards, the result of centuries of persecution and forced isolation in Christian lands. The solution was the full assimilation of the Jews into European societies. Much of what he wrote in his reviews of anti-Semitic authors like Eugen Dühring’s The Jewish Problem as a Problem of Racial Character and Its Danger to the Existence of Peoples, Morals and Culture and Wilhelm Jensen’s The Jews of Cologne, reflected ideas that would have been prevalent in Albia, that Jewish morality was corrupted by commercial greed, that the Jews were an oriental people alien to Europe, that Judaism was narrow-minded and superstitious and that Jewish physical features were deformed. According to Kornberg, “Equally, his solution was the disappearance of Jewry, or in his formula, cross-breeding on the basis of a common state-religion.”[64]

Despite Wagner’s known writings against Jews, Herzl was an avid admirer of Wagner’s music. Hermann Bahr, Herzl’s fraternity brother in Albia, asserted, “Every young person was a Wagnerian then. He was one before he had ever heard a single bar of his music.” Mahler, who was born in Bohemia to Jewish parents of humble origins, was devoted to Wagner and his music, and at aged 15 he sought him out on his 1875 visit to Vienna. As Herzl remarked, “I worked on it [The Jewish State] every day to the point of utter exhaustion. My only recreation was listening to Wagner’s music in the evening, particularly to Tannhäuser, an opera which I attended as often as it was produced, only on the evenings when there was no opera did I have any doubt as to the truth of my ideas.”[65]

However, in 1883, when Albia held a memorial ceremony for Wagner in March 1883, at which fiercely anti-Semitic speeches were made, Herzl asked to be discharged from the association on honorable terms. At the onset of the ceremonies the orchestra played Wagner’s music and the audience sang “Deutscland über alles.” A speaker extolled German nationalism and the Reich, and another declared “there can be only one German Reich.”[66] When the police stepped forward to prevent any further treasonous utterances, Shönerer rushed to the platform and proclaimed “Long Live Our Bismarck!”[67] However, according to Kornberg, “Herzl was not protesting against anti-Jewishness, which was compatible with full assimilation, but against racial antisemitism, which sought to drive Jews back into the ghetto.”[68]

Providing a clue to his association with German nationalism, Herzl wrote, “Do you know how the German empire was made? Out of dreams, songs, fantasies, and black-red-gold ribbons—and in a short time. Bismarck only shook down the fruit of the tree which the masters of fantasy had planted.”[69] Likewise, Friedjung advised, “If it is now the highest duty of the political writer to work on that obscure first principle of all national history, on the national character… then we must introduce into public life a powerful new force: national feeling.” It was the power of art which was to make this possible. Inspired by Wagner, Friedjung noted, “Orpheus dared to walk with his lyre among the powers of the underworld only because he knew there lives in the obscure masses a feeling, a dark presentiment that will be awakened to thundering emotion by a full tone.”[70]

As the Paris correspondent for Neue Freie Presse, Herzl followed the Dreyfus affair, a political scandal that divided the Third French Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. It was a notorious anti-Semitic incident in France in which Alfred Dreyfus (1859 – 1935), a Jewish French army captain, was falsely convicted in 1894 of spying for Germany. Known as the Dreyfus affair, it became one of the most controversial and polarizing political dramas in modern French history and throughout Europe. It ultimately ended with Dreyfus’ complete exoneration. Herzl claimed that the Dreyfus case turned him into a Zionist and that he was particularly affected by chants from the crowds of “Death to the Jews!.” However, some modern historians now consider that, due to few mentions of the Dreyfus affair in Herzl’s earlier accounts, and a apparently contrary reference he made in them to shouts of "Death to the traitor!” that he may have exaggerated its influence on him in order to create further support for his cause.[71] Kornberg claims that the influence Dreyfus was a myth that Herzl did not feel it necessary to refute and that he also believed that Dreyfus was guilty.[72]

In 1897, at considerable personal expense, Herzl founded the Zionist newspaper Die Welt in Vienna, and planned the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. He was elected president of the Congress, a position he held until his death in 1904. In 1898, he began a series of diplomatic initiatives to build support for a Jewish country. He was received by Wilhelm II on several occasions, one of them in Jerusalem, and attended the Hague Peace Conference, enjoying a warm reception from many statesmen. Herzl appealed to the nobility of Jewish England, the Rothschilds, Sir Samuel Montagu, later cabinet minister, to the Chief Rabbis of France and Vienna, the railroad magnate, Baron Maurice de Hirsch (1831 – 1896). In preparatory notes for his appeal to the Jewish philanthropist Baron Hirsch to underwrite the Jewish State, Herzl concluded his request with the words “Honor, Freedom, Fatherland,” the old Albia motto.[73] Beginning in late 1895, Herzl wrote Der Judenstaat (“The State of the Jews”), published 1896 to immediate acclaim and controversy, which argued that the Jewish people should leave Europe for Palestine, as their only opportunity to avoid anti-Semitism, express their culture freely and practice their religion without hindrance.

Anthroposophy

The Ariosophists, who were initially active in Vienna before World War I, combined German völkisch nationalism and racism with occult notions borrowed from the theosophy of Helena P. Blavatsky, in anticipation of a coming era of German world rule. As described by Nicholas Goodrick-Clark, “The ideas and symbols of ancient theocracies, secret societies, and the mystical gnosis of Rosicrucianism, Cabbalism, and Freemasonry were woven into the völkisch ideology, in order to prove that the modern world was based on false and evil principles and to describe the values and institutions of the ideal world.”[74]

As noted by Goodrick-Clarke, Theosophy “enjoyed a considerable vogue in Germany and Austria.”[75] Its advent was tied to a wider neo-romantic protest movement in Germany known as Lebensreform (“life reform”), a type of proto-hippie movement that explored alternative life-styles, including herbal and natural medicine, vegetarianism, nudism and living in communes.[76] In July 1884, the first German Theosophical Society (GTS) was established under the presidency of Wilhelm Hübbe-Schleiden (1846 – 1916), whose periodical The Sphinx was a powerful influence in the German occult revival until 1895. In 1883, Hübbe-Schleiden became acquainted with the teachings at Elberfeld, where Blavatsky and her chief collaborator, Henry Steel Olcott, were staying with their Theosophical friend Mary Gebhard, a pupil of Éliphas Lévi.[77] A few weeks after the foundation, they were joined by Blavatsky herself. At the end of 1894, Hübbe-Schleiden traveled to India to find out about the spiritual power of yoga through his own experience, and published the impressions in The Sphinx. Following a request from Annie Besant, Hübbe-Schleiden had introduced the Order of the Star of the East in Germany, which proclaimed the Hindu boy Jiddu Krishnamurti world teacher.

Franz Hartmann (1838-1912), founding members of the OTO.

Among Hübbe-Schleiden ’s circle at this time were Franz Hartmann (1838 – 1912), one of the founding members of the OTO, and the young Rudolf Steiner (1861 – 1925), founder of the Waldorf schools, who were both members of the GTS. Hartmann went to visit Blavatsky at Adyar, India, travelling by way of California, Japan and South-East Asia in late 1883. Hartmann had established himself as a director of a Lebensreform sanatorium at Hallein near Salzburg upon his return to Europe in 1885. A German Theosophical Society, as a branch of the International Theosophical Brotherhood, had been established in 1896, with Hartmann as its president. f was a member of a Theosophical Society founded in Vienna in 1887, whose president was Friedrich Eckstein, a friend and temporary co-worker of Sigmund Freud. Eckstein was a member of a Lebensreform group and was interested in Spanish mysticism, the legends surrounding the Templars, the Freemasons, Wagnerian mythology, and oriental religions.[78]

Steiner and Annie Besant

After parting with the Theosophical Society, Steiner founded a spiritual movement, called anthroposophy, with roots in German idealist philosophy and theosophy. Other influences include Goethean science and Rosicrucianism. Steiner, who in 1895 had written one of the first books praising Nietzsche, visited him when he was in his sister Elisabeth’s care in 1897. Elisabeth even employed Steiner as a tutor to help her to understand her brother’s philosophy.[79] Referring to Nietzsche’s mental illness, Steiner said, “In inner perception I saw Nietzsche’s soul as if hovering over his head, infinitely beautiful in its spirit-light, surrendered to the spiritual worlds it had longed for so much.”[80] Steiner was a member of the völkisch Wagner club, and anthroposophical authors endorsed Wagner’s views on race.[81] In 1906, Theodor Reuss issued a warrant to Steiner, making him Deputy Grand Master of a subordinate O.T.O./Memphis/Mizraim Chapter and Grand Council called “Mystica Aeterna” in Berlin.

Steiner published a periodical Luzifer in Berlin from 1903 to 1908. From 1906 to 1914, Steiner was the Sovereign Grand Master in Germany of the Rite of Memphis-Misraim, to which he added a number of Rosicrucian references.[82] Steiner had been made general secretary of the German Theosophical Society in 1902. By 1904, Steiner he was appointed by Annie Besant to be leader of the Theosophical Esoteric Society for Germany and Austria. Steiner finally broke away to found his own Anthroposophical Society in 1912. Steiner’s vocal rejection of Leadbeater and Besant’s claim that Jiddu Krishnamurti was the vehicle of a new Maitreya, or world teacher, led to a formal split in 1912, when Steiner and the majority of members of the German section of the Theosophical Society broke off to form a new group, the Anthroposophical Society.

While Blavatsky wrote about the Zoroastrian struggle between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman, as the forces of light and darkness, Steiner put forward a dualism that pitted Lucifer against Ahriman. In Occult Science, An Outline, Steiner characterized Lucifer as a being of light, the mediator between Man and God, bringing us closer to Christ. The “Children of Lucifer,” are therefore those who strive for wisdom, while Ahriman leads mankind downward to its lower, material, carnal, animalistic nature. Since people have perverted Christ’s actual teachings, Maitreya, as the Antichrist, will come from Shambhala and purge the world of their blemish and teach the true message of Christ.[83]

List Society

Guido von List (1848 – 1919)

In 1918, the völkisch List Society began to attract distinctive members, including the complete membership of the Vienna Theosophical Society, and its president Franz Hartmann. The List Society was founded by Austrian occultist Guido von List (1848 – 1919), the first popular writer to combine völkisch ideology with occultism and theosophy. The List Society adopted the Golden Dawn system of hierarchical and initiatory degrees.[84] List was strongly influenced by the Theosophical thought of Madame Blavatsky. Hartmann himself explained how List’s teachings, especially on racial doctrine bore remarkable resemblance to those of Blavatsky.

The success of List’s 1888 novel Carnuntum caught the attention of Pan-German publishers Georg von Schönerer and Karl Wolf, who commissioned similar works.[85] List was also supported by Karl Lueger (1844 –1910), the mayor of Vienna, who was also a supporter of von Schönerer and the German National Party. Lueger was known for his antisemitic rhetoric and referred to himself as an admirer of Edouard Drumont, who founded the Antisemitic League of France in 1889. Asked to explain the fact that many of his friends were Jews, Lueger famously replied, “I decide who is a Jew.”[86] Decades later, Adolf Hitler, an inhabitant of Vienna from 1907 to 1913, saw Lueger as an inspiration for his own views on Jews.

Odin the Wanderer (1896) by Georg von Rosen

List, who was born to a wealthy middle-class family in Vienna, claimed that he abandoned his family’s Catholic faith in childhood, and devoted himself instead to the pre-Christian god Wotan (Odin). List expounded a new modern Pagan religious movement known as Wotanism, which he claimed was the revival of the religion of the ancient German race, and which included an inner set of Ariosophical teachings that he termed Armanism. He placed a völkisch emphasis on the folk culture and customs of rural people, believing them to represent a survival of this pre-Christian, pagan religion. He promoted the millenarian view that modern society was degenerate, but that it would be transformed through an apocalyptic event resulting in the establishment of a new Pan-German Empire that would embrace Wotanism.

List’s Wotanism was constructed largely on the Prose Edda and the Poetic Edda, two Old Norse textual sources which had been composed in Iceland in the thirteenth century. However, much of List’s understanding of the ancient past was based not on empirical research into historical, archaeological, and folkloric sources, but rather on ideas that he claimed to have received as a result of clairvoyant illumination which he received in a trance state.[87] In the 1890s, List initially devised the idea that ancient German society had been led by a hierarchical system of initiates, the Armanenschaft, an idea which had developed into a key part of his thinking by 1908. List’s image of the Armanenschaft’s structure was based largely on his knowledge of Freemasonry. He claimed that the ancient brotherhood had consisted of three degrees, each with their own secret signs, grips, and passwords.[88]

According to List, when the German tribes were forced to convert to Christianity, the priest-kings set about the creation of secret societies, which would be responsible for preserving the Armanist gnosis. He imagined the secret Kalander as the social precursors of the medieval corporations of guilds akin to Masonic lodges. The three guilds List listed as the purveyors of this sacred heritage were the skalds and minstrels, the heralds and masons, and lastly the secret tribunals of the Vehmgericht, or Holy Vehm, which represented an occult survival of Ario-Germanic law. The obscure letters on the Vehm dagger he reckoned to be a transliteration of a double SS sig-rune followed by two swastikas. List believed that all the red crucifixes and wheel-crosses in Catholic regions of Central Europe marked the locations of their secret courts.[89]

According to Eliphas Lévi, the dagger of the Vehm was in the form of a cross, and their code was published in the Reichstheater of Max Müller under the title The Code and Statutes of the Holy Secret Tribunal of Free Counts and Free Judges of Westphalia, established in the year 772 by the Emperor Charlemagne and revised in 1404 by King Robert, who made those alterations and additions requisite for the administration of Justice in the tribunals of the Illuminated, after investing them with his own authority. A warning on the first page forbade a profane from reading any further under penalty of death. As Levi explained:

…the word “illuminated” here given to the associates of the Secret Tribunal, unfolds their entire mission: they had to track down in the shadows those who worshipped the darkness; they counterchecked mysteriously those who conspired against society in favour of mystery; but they were themselves secret soldiers of light, who cast the light of day on criminal proceedings.[90]

List claimed that after the Christianization of Northern Europe, the Armanist teachings were passed down in secret, resulting in their transmission through the traditions of Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry.[91] According to List, a number of prominent Renaissance humanists, including Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, Giordano Bruno, Johannes Trithemius, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, and Johann Reuchlin, were all inheritors of this ancient Armanist teaching, with List claiming that he was actually the reincarnation of Reuchlin.[92] Additionally, List claimed that in the eighth century, Armanists had imparted their secret teachings to the Jewish rabbis of Cologne in the hope of preserving them from Christian persecution. List believed that these teachings became the Kabbalah, thus legitimizing its usage in his own teachings by claiming it as an ancient German and rather than Jewish development.[93]

List also preached the advent of a pan-German millennium, a new Ario-Germanic world state. List generally saw the world in which he was living as one of degeneration, comparing it with the societies of the Late Roman and Byzantine Empires. A staunch monarchist, he opposed all forms of democracy, feminism, and modern trends in the arts. He was opposed to laissez-faire capitalism and large-scale enterprise. He condemned all finance as usury and indulged in period anti-Semitic sentiments culled from the newspapers of Georg von Schönerer and Aurelius Polzer. He was similarly opposed to the modern banking sector and financial institutions, deeming it to be dominated by Jews.[94] List believed that the degradation of modern Western society was as a result of a conspiracy orchestrated by a secret organization known as the Great International Party.[95] Adopting a millenarianist perspective, he believed in the imminent defeat of this enemy and the establishment of a better future for the Ario-German race.[96]

In April 1915, List welcomed the start of World War I as a conflict that would bring about the defeat of Germany’s enemies, and he believed that the German war dead would be reincarnated as a generation who would push through with a national revolution and establish this new Ario-German Empire.[97] For List, this ideal future would be intricately connected to the ancient past, reflecting his belief in the cyclical nature of time, a notion which he had adopted both from a reading of Norse mythology and from Theosophy. As early as 1891, List had discovered a verse Starke von Oben (“Strong One from Above”) prophecy of the “Voluspa,” the first and best-known poem of the Poetic Edda, which heralded the coming of a messianic figure:

A wealthy man joins the circle of counsellors,

A Strong One from Above ends the faction,

He settles everything with fair decisions,

Whatever he ordains shall endure for ever.

This Starke von Oben became a recurring motif in all List’s subsequent references to the millennium. An ostensibly superhuman individual would end all human conflict with the establishment of an eternal order. Reflecting his monarchist beliefs, he envisioned this future state as being governed by the House of Habsburg.[98] In List’s opinion, this new empire would be highly hierarchical, with non-Aryans being subjugated under the Aryan population and opportunities for education and jobs in public service being restricted to those deemed racially pure.[99] He envisioned this Empire following the Wotanic religion which he promoted.[100]

Theozoology

Lanz von Liebenfels (1874 – 1954)

There were multiple links between the Theosophical Society and the ariosophists. An example was Max Seiling (1852 – 1928), who was also involved in the anthroposophist movement and became a member of the Guido von List Society. When List’s Die Bilderschrift der Ario-Germanen, appeared in 1910, Hartmann praised it in his Theosophical periodical Neue Lotusblüthen. In 1901, the Theosophist Paul Zillmann began to carry Lanz von Liebenfels essays in his journal Neue Metaphysische Rundschau. Zillmann joined the Guido von List Society a year later.[101] Prana, an occult German monthly published by the Theosophical publishing house in Leipzig, featured contributions by List, Hartmann and C.W. Leadbeater.[102]

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (1090 – 1153), patron of the Templars

In the 1890s, List was involved with a Viennese literary society, which included Rudolf Steiner and Lanz von Liebenfels (1874 – 1954), who like List, was also from Vienna. Lanz had been a monk in the Cistercian Order—to which had belonged St. Bernard of Clairvaux, patron of the Templars—but was finally expelled in 1899 for acts of “carnal love.”[103] Lanz was also the founder of the Order of New Templars (Ordo Novi Templi, or ONT) an offshoot of the OTO, which practiced tantric sex rituals.[104] To von Liebenfels, the Templars were an Aryan brotherhood dedicated to the establishment of a greater Germany and to the purification of the race. He believed the Grail was symbolic of the pure German blood.[105] In 1905, he founded the magazine Ostara, in which he published anti-Semitic and völkisch theories. Readers included Adolf Hitler, Dietrich Eckart and the British Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener among others. Lanz claimed he was visited by the young Hitler in 1909, when he supplied him with two missing issues of the magazine.[106]

Von Liebenfels coined the term “Ariosophy,” playing on the term “theosophy,” distinguishing between the Theosophical goal of achieving “wisdom of God,” to achieving the “wisdom of the Aryans.”[107] In 1905, von Liebenfels published his book Theozoölogie oder die Kunde von den Sodoms-Äfflingen und dem Götter-Elektron (“Theozoology, or the Science of the Sodomite-Apelings and the Divine Electron”) in which he advocated eugenics and glorified the Aryan race as Gottmenschen (“god-men”). Lanz justified his theories on an interpretation of the Bible, according to which Eve was initially a divine being, but mated with a demon and gave birth to the “lower races.” This led to blonde women being attracted primarily to “dark men,” which could be prevented by “racial demixing” so that the “Aryan-Christian master humans” could “once again rule the dark-skinned beastmen” and ultimately regain divinity.

Von Liebenfels shared his conception of Atlantis with Karl Georg Zschaetzsch (b. 1870), whose major works were Herkunft und Geschichte des arischen Stammes “Origin and History of the Aryan Tribe” published in 1920 and Atlantis, die Urheimat der Arier (“Atlantis, the Aryans’ Original Home”) in 1922, which became bestsellers in Germany between the wars. According to Zschaetzsch the only three great Aryan survivors of Atlantis included Odin, his son Thor and his sister and then wife Freya, from which all later Aryans descended. In the biblical tradition, these three then became God the Father, Adam and Eve. The Aryans descended from them had subjugated the world from Atlantis and founded colonies worldwide, mingling with non-Aryan natives, and producing advanced civilizations such Egypt, Mesopotamia, Ancient Athens, and Peru. However, these cultures had also been destroyed due to the continued racial mixing. The last “pure” Aryans spread from Northern Europe to Germania and the Eastern European Baltic States to Southern Europe, Africa and Asia, where they would continue to mix. For his history, Zschaetzsch not only included the gods of Greek mythology, but also the entire Jewish-Biblical tradition, ancient American traditions and most pre-Christian pagan cults and festivals, all of which he interpreted as misunderstood or distorted versions of a supposed Atlantic prehistory.

In Die Geschichte der Ariosophie (“The History of Ariosophy”), written between January 1929 and June 1930, von Liebenfels claimed to trace the history of the ariosophical racial religion and its struggles since earliest times to the present. He asserted that the gods were Theozoa, an earlier and superior forms of life with electromagnetic sensory organs and superhuman powers, distinct from Adam’s progeny of Anthropozoa. According to von Liebenfels, the earliest recorded ancestors of the present “arioheroic” race were the Atlanteans, supposedly descended from the original divine Theozoa, who had lived on a continent situated in the northern part of the Atlantic Ocean. Catastrophic floods eventually submerged their continent around 8000 BC. The Atlanteans migrated eastwards in two groups: the Northern Atlanteans teemed towards the British Isles, Scandinavia, and Northern Europe, while the Southern Atlanteans migrated across Western Africa to Egypt and Babylonia, where they founded the antique civilizations of the Near East. Thus, the ariosophical cult was introduced to Asia, where the idolatrous beast-cults of miscegenation flourished.

Von Liebenfels claimed that the ariosophical religion was championed in the ancient world by Moses, Orpheus, Pythagoras, Plato, and Alexander the Great. The laws of Moses and Plato’s caste of philosopher-kings in The Republic proved them to have been Ariosophists. Von Liebenfels identified the revival of Ariosophy in the Benedictine monastics tradition of medieval Europe. Von Liebenfels celebrated Cistercian Order and its famous leader St. Bernard of Clairvaux as the principal force behind Ariosophy in the Middle Ages.[108] Because of their close association with the Cistercian Order, von Liebenfels regarded the Templars as the armed guard of Ariosophy, by attempting to stem the tide of inferior races in the Near East, and so provide a bulwark for racial purity of Aryan Christendom. Their efforts were paralleled in the west by the military orders of Calatrava, Alcantara, and Aviz, which had been formed during the mid-twelfth century to fight the Moors in Spain. The suppression of the Templars in 1308 signaled the end of this era and the rise of the racial inferiors. He claimed that Ariosophy survived due to an underground tradition of “several spiritual orders and genial mystics.” Their first link was the Order of Christ, and the two Habsburg houses of Spain and Austria, who were agents of a new ariosophical empire.

Count Nikolaus von Zinzendorf (1700 – 1760) founder of the Moravian Church influenced by Sabbateanism

In the Middle Ages this “ario-christian” tradition of mystics included: Meister Eckhart, Jakob Boehme, Count Nikolaus von Zinzendorf and Emanuel Swedenborg. After the Enlightenment, the list featured romantic thinkers and occultists of the nineteenth century including: Johann Baptist Krebs (1774 – 1851), the mystical Freemason who published under the pseudonym Johann Baptist Kerning. Krebs developed a consonant-vowel-based form of yogic practice, which was published by his pupil and successor Karl Kolb in “The Rebirth, the Inner True Life.” In 1896, OTO founder Carl Kellner commented that “Krebs who published on this topic in the 1850s under the pen name Kerning [...] represent the best that has ever been written in German about yoga practices, albeit in a form that might not be to everyone’s taste.”[109] Krebs also influenced Carl Graf zu Leiningen-Billigheim and Friedrich Eckstein, who led the Viennese Lodge of the Theosophical Society, but also practiced Masonic works “in the Art Kernings.”[110]

Others in Liebenfels’ list included were Carl von Reichenbach (1788 – 1869), the Viennese investigator of animal magnetism emanating from all living things, which he called the Odic force.[111] Also included were the French occultists, Eliphas Lévi, Josephin Péladan, Papus, H.P. Blavatsky, Franz Hartmann, Annie Besant, Charles Leadbeater and Eduard Schuré (1841 – 1929), a French publicist of esoteric literature, a member of Max Theon’s Cosmic Movement. Schuré called the three most significant of his friendships those with Richard Wagner, Marguerita Albana Mignaty and Rudolf Steiner.[112] Impressed by Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, he sought out the composer’s personal friendship. In 1873, he met Friedrich Nietzsche who shared his enthusiasm for Wagner. In 1884, he met H.P. Blavatsky and joined the Theosophical Society. In 1889, Schuré published his major work, Les Grands Initiés (“The Great Initiates”). The tradition finally led to Guido von List, Rudolf John Gorsleben (1883 – 1930), and the mythologists of an Aryan Atlantis, Zschaetzsch and Hermann Wieland.[113] Gorsleben was a German Ariosophist and Armanist who formed the Edda Society and wrote the book Hoch-Zeit der Menschheit (“The Zenith of Humanity”), first published in 1930, which is known as “The Bible of Armanism.”[114]

German Disease

As Peter Levenda has additionally pointed out, in Unholy Alliance, it is likely that the homosexuality of the Nazi hierarchy was inherited from the sexual practices promoted by Aleister Crowley. Both Liebenfels and List, who influenced the ideas of the Nazis, were also homosexuals. Prior to the war, homosexuality remained at a moderate level in Germany. After the war, however, it become so widespread that people in England and France began to refer to it as the “German disease.” Eventually, note the authors of The Hidden Holocaust, “homosexuality rose so much in Germany that immediately after the Marxist revolution, homosexuals use the unbridled freedom of the time to form clubs and associations that would represent their interests.”[115]

It is well known that the Nazis persecuted homosexuals, as they did Jews, Gypsies and other “inferiors.” However, as openly gay columnist for the London Independent, Johann Hari, in an article titled “The Strange, Strange Story of the Gay Fascists,” dared to acknowledge, “there has always been a weird, disproportionate overlap between homosexuality and fascism.” As the authors of The Pink Swastika demonstrate, the Nazi persecution of homosexuals was reflective of a conflict that typically divides the gay community, between “fems” and “butches.” As Hari further explained, the Nazis “promoted an aggressive, hypermasculine form of homosexuality, condemning ‘hysterical women of both sexes’, in reference to feminine gay men.”[116]

Effectively, the Nazis perceived the height of veneration of the purported masculine virtues to be fulfilled through homosexual relations, a practice common in warrior societies like ancient Sparta. Eva Cantarella, a classicist at the University of Milan stated that, “The most warlike nations have been those who were most addicted to the love of male youths.”[117] Such societies are profiled in The Sambia, by anthropologist Gilbert Herdt, who studied homosexuality in various societies, who wrote that “ritual homosexuality has been reported by anthropologists in scattered areas around the world [revealing a]… pervasive link between ritual homosexuality and the warrior ethos... We find these similar forms of warrior homosexuality in such diverse places as New Guinea, the Amazon, Ancient Greece, and historical Japan.”[118]

According to the authors of The Pink Swastika, the Nazi homosexuals, “were militarists and chauvinists in the Hellenic mold. Their goal was to revive the pederastic military cults of pre-Christian pagan cultures, specifically the Greek warrior cult.”[119] Plutarch, a Greek historian of the first century AD, stated: “it was chiefly warlike peoples like the Boeotians, Lacedemonians and Cretans, who were addicted to homosexuality.”[120] Cantarella notes that Plutarch wrote of “the sacred battalion” of Thebans made up of 150 male homosexual pairs, and of the legendary Spartan army, which inducted all twelve-year-old boys into military service where they were “entrusted to lovers chosen among the best men of adult age.”[121] Sparta was the inspiration for the fascist state found in Plato’s The Republic, and Plato had Phaedrus, in the opening speech of the Symposium, praise homosexuality in the following manner:

For I know not any greater blessing to a young man who is beginning life than a virtuous lover, or to the lover, than a beloved youth. For the principle which ought to be the guide of men who would live nobly – that principle, I say, neither kindred, nor honour, nor wealth, nor any other motive is able to implant so well as love ... And if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their loves, they would be the very best governors of their own city ... and when fighting at each other's side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world.

Since the open homosexuality of the Greeks was the ideal, German psychoanalyst, Wilhelm Reich in his 1933 classic, The Mass Psychology of Fascism, explained:

For the fascists, therefore, the return of natural sexuality is viewed as a sign of decadence, lasciviousness, lechery, and sexual filth... the fascists... affirm the most severe form of patriarchy and actually reactivate the sexual life of the Platonic era in their familial form of living... Rosenberg and Bluher [the leading Nazi ideologists] recognize the state solely as a male state organized on a homosexual basis.[122]

Benito Mussolini (1883 – 1945)

It was at the beginning of the century that the code of the Superman was embraced in Italy, with the purpose of infusing new life into what ought to be pursued as the New Man, or the masculine ideal, in addition to that of the New Italy, which for Mussolini, signified a fascist government where he was the dictator in full control. After having been elected to power in 1922, Mussolini crafted a myth of himself adapting the image of the Nietzsche’s Übermensch. Mussolini emphasized how Nietzsche had advocated an imminent return to the ideal, stating that “a new kind of ‘free spirit’ will come, strengthened by the war… spirits equipped with a kind of sublime perversity… new, free spirits, who will triumph over God and over Nothing!”[123] Mussolini believed that the virility of male bodies was essential and he attempted to reconstruct the ancient and warlike “Italian descent.” The New Italian was encouraged to assume the Fascist style, which included ideals of male beauty proposed by the regime. [124]

[1] Novak. Jacob Frank, Le Faux Messie, p. 129.

[2] Plato. Symposium, 211b–d; cited in Yulia Ustinova. Divine Mania Alteration of Consciousness in Ancient Greece (Routledge, 2018), p. 297; see David Livingstone. Ordo ab Chao. Volume One, Chapter 1: Ancient Greece, Plato.

[3] Aleister Crowley. Magick, Book 4. p. 127.

[4] Aleister Crowley. The Book of the Law in Magical and Philosophical Commentaries on the Book of the Law (Publishing: Montreal, 1974) p. 93.

[5] Nietzsche. Human, All-too-Human, 477.

[6] Nietzsche. Beyond Good and Evil, Chapter 9, “What is Noble?”

[7] Nietzsche. Genealogy of Morals, II:17

[8] Giles Fraser. “On the Genealogy of Morals, part 3: The birth of the übermensch.” The Guardian (November 10, 2008).

[9] Nietzsche. Genealogy of Morals.

[10] Barbara Spackman. Fascist Virilities: Rhetoric, Ideology, and Social Fantasy in Italy (University of Minnesota Press, 1996), p. 2.

[11] Sandro Bellassai (2005). “The masculine mystique: anti-modernism and virility in fascist Italy.” Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 3, 314-335

[12] Nietzsche. Ecce Homo.

[13] Steven E. Aschheim. The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany, 1890-1990 (University of California Press, 1992) p. 27.

[14] Isadora Duncan. Isasora Speaks, ed. Franklin Rosemont (San Francisco: City Light Books, 1983), p. 121.

[15] Walter Kaufmann. Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist (Princeton University Press, 1974), p. 67; Anacleto Verrecchia, “Nietzsche’s Breakdown in Turin,” Nietzsche in Italy, ed. Thomas Harrison (Stanford University: ANMA Libri, 1988) pp. 105-12.

[16] Joachim Köhler. Zarathustra’s secret: the interior life of Friedrich Nietzsche (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002) pp. xv.

[17] Karl Dietrich Bracher. The German Dictatorship (1970), pp. 59-60.

[18] Jack Wertheimer. Unwelcome Strangers (Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 165.

[19] David Cesarani & Sarah Kavanaugh. Holocaust: Hitler, Nazism and the "Racial State" (Psychology Press, 2004), p. 78.

[20] Herbert A. Strauss. Hostages of Modernization: Studies on Modern Antisemitism, 1870-1933/39 (Walter de Gruyter, 1993), p. 72.

[21] Jean-Yves Camus & Nicolas Lebourg. Far-Right Politics in Europe (Harvard University Press, 2017).

[22] Andy Walker. “1913: When Hitler, Trotsky, Tito, Freud and Stalin all lived in the same place.” BBC Magazine (April 18, 2013).

[23] Abraham G. Duker. “Polish Frankism’s Duration: From Cabbalistic Judaism to Roman Catholicism and From Jewishness to Polishness,” Jewish Social Studies, 25: 4 (1963: Oct) p. 292.

[24] Gershom Scholem. “Redemption Through Sin,” The Messianic Idea in Judaism and Other Essays, pp. 78–141.

[25] Cited in Jacques Kornberg. Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism (Indiana University Press, 1993), p. 30.

[26] Andy Walker. “1913: When Hitler, Trotsky, Tito, Freud and Stalin all lived in the same place.” BBC Magazine (April 18, 2013).

[27] Elliott Horowitz. “Coffee, Coffeehouses, and the Nocturnal Rituals of Early Modern Jewry.” AJS Review, Volume 14, Issue 1 (April, 1989).

[28] Eileen M. Lavine. “The Stimulating Story of Jews and Coffee.” Moment (Sunday 2, 2016)

[29] “A Viennese grind.” The Economist (July 30, 2009).

[30] Andrew Alderson. “Banker Julius Meinl V loses legal action to magazine that ‘portrayed him as Hitler’.” The Daily Telegraph (July 24, 2010).

[31] Ibid.

[32] William R. Denslow. 10,000 Famous Freemasons, 4 vol., Missouri Lodge of Research (Trenton, Missouri, 1957-61).

[33] Ronald F. Musto. Apocalypse in Rome: Cola di Rienzo and the Politics of the New Age (University of California Press, 2003).

[34] Guido Ruggiero. The Renaissance in Italy: A Social and Cultural History of the Rinascimento (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 227.

[35] Daniel Stern (Marie d’Agoult). Mes souvenirs (Bibliothèque contemporaine, 1880), p. 71.

[36] Osterrieder. “Synarchie und Weltherrschaft,” p. 108.

[37] Barry Millington, (ed.). The Wagner Compendium: A Guide to Wagner's Life and Music (revised edition), (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 2001), pp. 140–4.

[38] Joachim Heinzle (ed.) Das Nibelungenlied und die Klage. Nach der Handschrift 857 der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen. Mittelhochdeutscher Text, Übersetzung und Kommentar (Berlin: Deutscher Klassiker Verlag, 2013), pp. 1021-1022.

[39] Richard Wagner. Letter to Mathilde Wesendonk (May 30, 1859).

[40] Theodor Adorno. In Search of Wagner (Verso, 1952); John Deathridge. “Strange love” in Western music and race (Cambridge UP, 2007).

[41] Dieter Borchmeyer. Drama and the World of Richard Wagner (Princeton University Press, 2003).

[42] David Conway. “‘A Vulture is Almost an Eagle’… The Jewishness of Richard Wagner.” Jewry in Music. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20121203090712/http://www.smerus.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/vulture_.htm; Robert W. Gutman. Richard Wagner: The Man, his Mind and his Music (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich, 1990).

[43] Johnson. Initiates of Theosophical Masters, p. 161.

[44] Dreyfuss. Hostage to Khomeini.

[45] Jacques Kornberg. Theodor Herzl: From Assimilation to Zionism (Indiana University Press, 1993), p. 49.

[46] Ibid., p. 40.

[47] Joseph Jacobs & S. Mannheimer. “Schönerer, Georg von.” Jewish Encyclopedia (1906).

[48] Brigitte Hamann. Hitler’s Vienna: A Portrait of the Tyrant as a Young Man (Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2010), p. 244.

[49] Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke. The Occult Roots of Nazism: The Ariosophists of Austria and Germany 1890-1935 (Wellingborough, England: The Aquarian Press, 1985), p. 10.

[50] Hannah Arendt. The Origins of Totalitarianism (New York 1973), p. 241.

[51] Kenneth Hite. The Nazi Occult (Bloomsbury, 2013).

[52] Brigitte Hamann. Hitler’s Vienna: A Portrait of the Tyrant as a Young Man (Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2010), pp. 13, 244.